Half a century ago, when P&G Paper Products Co. put one of its biggest paper products plants in Mehoopany, Pa., its reasons for doing so were more than paper thin. The location — driven by access to wood, water and workforce — put the company’s products close to more than half the US population.

Little did P&G leaders know it put them close to another valuable resource directly under their feet.

In 1965, having patented the through-air drying process that meant softer, more absorbent tissue and paper towel products that consumers loved, it made little sense to keep shipping from Green Bay, Wis. — where the Charmin Paper Products Company product, purchased by P&G in 1957, was founded — when so many of those consumers lived in the US Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. The decision to also expand their new Pampers disposable diaper business into more manufacturing locations for similar reasons also had P&G looking for a new manufacturing site. Even today, says Mehoopany Public Relations, Health, Safety, Environmental Affairs & Energy Affairs Manager Alex Fried, a fully loaded tractor-trailer only weighs about 20,000 pounds. It was time to establish another manufacturing base closer to those consumers.

The Wyoming County site in Mehoopany, directly on the mighty Susquehanna River, got the nod. By October 1966, the plant was up and running. Today it’s home to approximately 2,000 employees, 1,000 associated contractors and a payroll of over $200 million annually. And next year it will celebrate 50 years of continuous operation without a single layoff.

With 90 acres under roof on the 1,400-acre site, the operation intakes 10 million gallons of water a day, discharging around 8.5 million gallons per day of water that Fried says is “actually cleaner than what we intake.” It’s the company’s biggest facility by capex, value of product and number of employees around the world.

It’s also significantly bigger when it comes to energy.

The company’s family care business altogether represents half of P&G’s global energy footprint, with the Mehoopany site alone representing 20 percent. “We typically need about 100,000 homes’ worth of power,” says Fried. Since 1985, about half of it comes from cogeneration. The site team has re-lamped from metal halide to the latest fluorescent fixtures, and made strides in capturing waste heat. “But we were interested in getting more off the grid.”

‘Interesting’ Proposition

Natural gas is a big component: The site used to use about 10 billion cu. ft. a year, a figure that’s now up to 13 billion, says Fried. The supply chain for that gas was 1,500 miles long, in the form of interstate pipelines from the Gulf of Mexico.

A signature moment for Pennsylvania — and, it turned out, for Charmin and Bounty — occurred in January 2008. That was when Penn State University Prof. Terry Engelder and SUNY Prof. Gary Lash published findings indicating that the natural gas black shale reservoir in northern Appalachia known as the Marcellus could boost the country’s proven reserves by trillions of cubic feet if exploration & production (E&P) companies used horizontal drilling techniques.

“The value of this science could increment the net worth of U.S. energy resources by a trillion dollars, plus or minus billions,” said Engelder in 2008.

At the time, all of North America produced roughly 30 trillion cubic feet of gas annually. Their conservative estimate said the Marcellus contained 168 trillion cubic feet. In December 2014, the Energy Information Administration said proved reserves in the Marcellus (meaning recoverable based on current prices and other supply factors) amounted to 64.9 trillion cubic feet, but ignoring price, said Engelder, the amount of technically recoverable gas in the formation comes to about 480 trillion cubic feet.

P&G was intrigued. All you had to do, says Fried, was look at a map.

“If you could, as a large industrial user using billions of cubic feet a year, transform your supply chain from 1,500 miles long to pretty much on your own property, that’s interesting,” Fried remembers thinking in 2008, three years after he’d assumed responsibility over energy affairs and knew down to the penny the cost of moving all that gas so far. The P&G team also knew they had a 12-inch, 700-psi gas line and other infrastructure, as well as mineral rights on about 1,400 acres. If there were gas on site, it was simply a matter of putting in a compressor station and moving the gas away from the site instead of towards it.

After considering proposals for about a year, P&G in March 2009 chose E&P firm Citrus Energy (purchased in July 2014 by Warren Resources) to come in under an oil and gas lease. “If it were found, we had a purchase contract to purchase all that gas,” says Fried. It would be attractive to the E&P firm too, as selling direct to a large industrial user precludes the need for purchasing pipeline capacity, and lowers compression requirements.

Moreover, “If gas were found, just like any other landowner, we’d get a nice, attractive royalty, and a lease bonus up front,” he says. And on top of that, because of the distance the gas had to travel from the Gulf, Fried says, “we used to have to buy 5 percent more gas than we needed. Purchasing locally “changes the game.”

P&G is winning that game, because Citrus (now Warren Resources) found some of the largest quantities of gas in the entire Northeast Pennsylvania play on P&G and neighboring property.

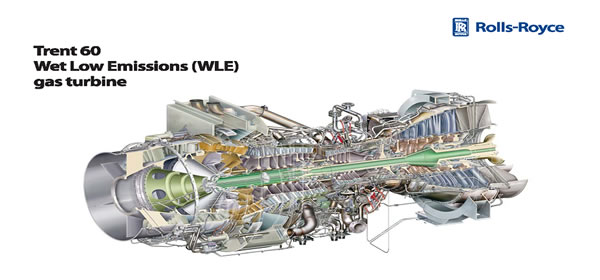

“Citrus found gas in late 2009, and by June 2010, the gas was able to move into our facility from our first well,” says Fried. “By fall 2010, we were full of natural gas,” and a year later in 2011 the pipeline flow had been fully reversed. Fried says the gas is purer than what came from the Gulf. And the reduction in costs (in the tens of millions of dollars annually) has enabled the Mehoopany team to invest more than $50 million in a multifaceted operation featuring a large Rolls-Royce turbine that produces electricity, and allows P&G to produce steam and hot air for its paper making process from the waste heat, meaning the shutdown of two boilers and a significant reduction in paper-machine gas used to produce hot air for the process.

That generator alone between May and November of 2013, its startup year, was delivering an annual gross savings of $16.5 million. Other waste heat goes to paper machines. The company is using the site’s original high voltage 115kv power lines to send power back into the grid.

“That makes us self-sufficient,” says Fried. “It’s really tri-generation — we’re making electricity, steam and hot air, all of which can be used on site.”

Moreover, CO2 emissions at Mehoopany have dramatically decreased by 120,000 metric tons per year.

Spinoff Effects

Oh, and one more thing: The prolific gas production meant P&G could pursue compressed natural gas (CNG) as an alternative fuel source for the 300 trucks a day the facility welcomes, as well as a fleet 52 forklifts, and 24 trucks that shuttle product to a 1.8-million-sq.-ft. warehouse a few miles away.

“We used to burn diesel to shuttle those products,” says Fried. “When you use CNG and have a very local supply chain, the most expensive components are the federal and state road fuels taxes, not the fuel.”

Because of that on-site success, it made sense to offer it to the approximately 300 daily over-the-road trucks that visit the Mehoopany site. P&G expanded its fueling station to accommodate them, and signed contracts with Schneider, Kane and Swift to run on CNG within a 200-mile radius. About 75 of those 300 trucks now use CNG.

“Those are lanes where we know the truck can go to the customer and get back without running out of fuel,” says Fried. “We’d love to go up to between 600 and 800 miles, but to do that consistently, we need more stations like this to refuel.”

CNG is greener too. And P&G is acutely aware of the sustainability factor. Fried explains that it was important to deal appropriately with the whole hot-button issue of fracking. The program at Mehoopany offered another well-placed opportunity, as the company has a capped landfill on site, closed since 1992, where it’s been monitoring the groundwater ever since. The area provided a very good test site, therefore, for putting the environmental safety claims of fracking to the test.

“We need to prove to ourselves that this process isn’t somehow creating environmental damage,” Fried’s team said to Citrus. “So we want you to put your first wells right there, because we have well monitors right there.”

P&G invested in similar groundwater wells at every drilling pad, and over five years has found no change in groundwater quality.

Drive up to the plant today, and you’ll see some of the five well pads on property. Fifteen wells on P&G property have been completed and are flowing to the plant. The site uses long-haul gas only for backup.