Ohio’s recent economic development news has been dominated by groundbreaking ceremonies. Intel and Amgen blaze a new technology-driven industrial corridor northeast of Columbus. Two electric mobility startups moved into the state: Joby Aviation’s electric air taxi will be Dayton-made, while Hyperion Motors purchased an abandoned newspaper printing plant to fabricate hydrogen fuel cell stacks in Columbus once the market develops.

Electric batteries are made in Northeast Ohio’s LG-GM Ultium factory, while Honda’s EV battery plant is under construction in downstate Fayette. Honda is also investing in its mid-Ohio assembly, transmission and engine plants to meet a hybrid future.

Metropolitan Toledo is home to First Solar and startup Toledo Solar. The south-central portion of the state has seen a lot of growth in warehousing and logistics, along with notable manufacturing investments by Sofidel and American Nitrile.

While Ohioans wait for these projects to develop, what is happening now?

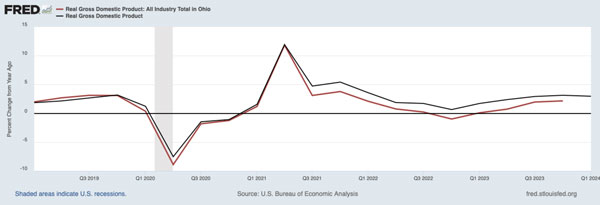

Cost-of-living-adjusted per capita income in Ohio is, and has been, above the national average, while growth in GDP moved in concert with the national average. However, an average gap of -1.2 percentage points in the GDP growth rate has persisted since 2021. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Quarterly 12-month Growth Rate in Real Gross Domestic Product for the U.S. and Ohio from 2019(1) to 2024(1) in 2017 dollars

Figure 1 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Quarterly 12-month Growth Rate in Real Gross Domestic Product for the U.S. and Ohio from 2019(1) to 2024(1) in 2017 dollars

Annual growth in real GDP in Ohio (red line) tracked growth in the U.S. (black line) economy from 2019 through the recovery from COVID-19. Ohio’s real GDP growth rate began to lag the national average in the summer of 2021. The question is: Why has the growth rate trailed the national average? The short-run answers are in the labor market. First, I compare Ohio’s Unemployment Rate (UR) to the national average, followed by the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR).

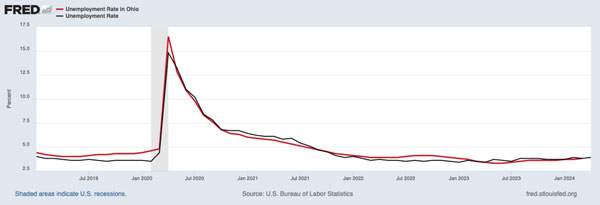

Figure 2 Unemployment Rate (UR) The monthly unemployment rate for the U.S. and Ohio from January 2019 to March 2024 for Ohio and April 2024 for the U.S.

Figure 2 Unemployment Rate (UR) The monthly unemployment rate for the U.S. and Ohio from January 2019 to March 2024 for Ohio and April 2024 for the U.S.

No statistical difference exists between the national and Ohio unemployment rates (Figure 2). However, this measure of unemployment is restricted to those who are not working and actively seeking work. It omits those who are not seeking work for whatever reason. A different measure of labor market activity — the Labor Force Participation Rate — indicates that there is either a discouraged worker challenge or employers are attracting potential workers to specific types of jobs (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) The monthly Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate for Ohio and the U.S. from January 2019 to March 2024 for Ohio and April 2024 for the U.S.

Figure 3 Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) The monthly Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate for Ohio and the U.S. from January 2019 to March 2024 for Ohio and April 2024 for the U.S.

Ohio’s Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) was either above or roughly even with the national average from January 2019 through March 2020; Ohio’s average LFPR was 63.1%. This relationship changed with the recovery from the March 2020 COVID-19 shock. In February 2021, Ohio’s LFPR was 0.1 percentage points, or 10 basis points, lower than the nation’s. In finance, a hundredth of a percent (0.01%) is called a basis point, 0.1% is 10 basis points, and 100 basis points constitute 1%. In labor economics and demographics, where meaningful differences in unemployment rates, labor force participation rates, and population growth rates are frequently less than 1%, discussing differences in terms of basis points prevents confusion.

The gap between the LFPRs in Ohio and the nation slowly and steadily grew from 10 basis points in February 2021 to 90 basis points in August 2022. Since that date, the gap has hovered between 70 and 90 basis points. This means that the share of Ohio’s adult population (age 20 and older) working or looking for work is below the national average.

Looking at national LFPRs by demographic groups provides some hypotheses about why the gap occurred (these data are unavailable for states). Comparing the national LFPRs from March 2020 to January 2024:

While the LFPRs for men are higher than for women, the LFPRs for men have not recovered to their pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, while proportionately more women left the labor force during the pandemic, the LFPRs for women had nearly recovered.

The two age groups with the lowest recovery rates pre- to post-COVID were those with the highest LFPRs — the heart of the labor market. In January 2024, the LFPR of those aged 20 to 24 was 250 basis points below their March 2020 level. Those aged 25 to 54 had an LFPR of 200 basis points below March 2020.

LFPRs increase with educational attainment. In January 2024, high school non-completers had LFPR of 47%, terminal high school graduates 57%, some higher education or associate degrees 63%, and bachelor’s degree holders and above 73%.

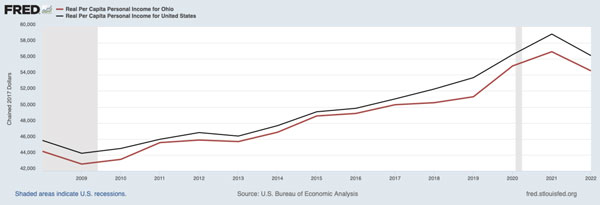

Figure 4 Real Per Capita Income Annual Real Per Capita Income for the U.S. and Ohio from 2008 to 2022 for Ohio and the U.S.

Figure 4 Real Per Capita Income Annual Real Per Capita Income for the U.S. and Ohio from 2008 to 2022 for Ohio and the U.S.

There are two more pieces to the puzzle about Ohio’s economic performance: real per capita income and real per capita income adjusted for the cost of living — which is where the surprise exists. Change in real per capita income is a good indicator of overall economic progress. I first plotted per capita income in Ohio (red line) and the U.S. (black line) in Figure 4, followed by the annual percent change in per capita real per capita incomes from 2009 to 2022 in Figure 5.

The nation and Ohio have had real average incomes increase throughout, except during the Great Recession and between 2021 and 2022. However, the average income in Ohio was lower throughout the period covered in Figure 4, and the gap between state and nation began to widen in 2018.

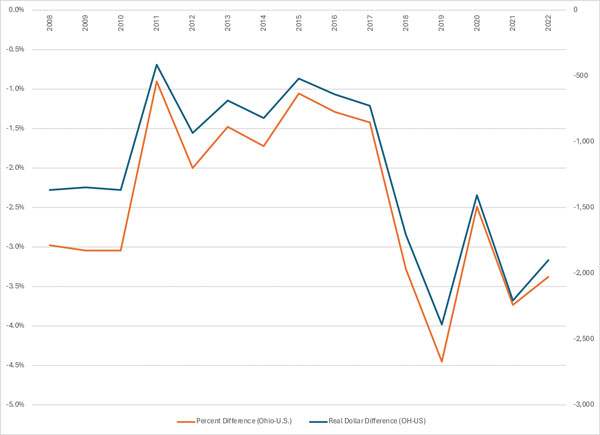

Figure 5 Annual Difference in Real Per Capita Income Differences in the Real Annual Percentage Change in Per Capita Income (left-axis) and The Real Dollar Change in Per Capita Income (right-axis) between Ohio and the United States (Ohio-U.S.) from 2008 and 2022.

Figure 5 Annual Difference in Real Per Capita Income Differences in the Real Annual Percentage Change in Per Capita Income (left-axis) and The Real Dollar Change in Per Capita Income (right-axis) between Ohio and the United States (Ohio-U.S.) from 2008 and 2022.

Figure 5 plots the annual difference in real per capita income in the U.S. and Ohio; the calculation subtracts the U.S. average from the Ohio average. The percentage difference between the two is plotted in red on the lefthand vertical axis, and the dollar difference is in blue and plotted against the vertical axis on the right.

The average difference in the annual growth rates was 2.4%; however, there was a change between 2017 and 2019 when the difference between the US and Ohio jumped from $727 to $2,389. These data are accurate, but they do not account for differences in the cost of living in Ohio and its regional labor market areas. This is done in Figure 6.

Adjusting Real Per Capita Incomes for Regional Variation in the Cost of Living

Here is the surprise: the relationship between Ohio and the U.S. changes after adjusting real per capita income for regional differences in cost of living. I used the regional price parities for states and regions produced by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis to account for cost-of-living differentials. The index is constructed so that the U.S. average is 100.0, and each state and metropolitan area has a price parity that is an index number interpreted as a percentage of the U.S. average. The parity indexes for Ohio and its metropolitan areas are lower than 100.0.

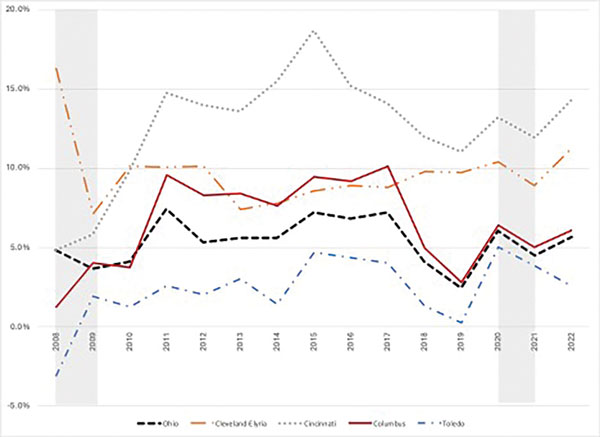

Figure 6 Real Per Capita Incomes Adjusted for Cost-of-Living Cost-of-living adjusted Real Per Capita Incomes in Ohio and the Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo Metropolitan Areas are above the National Average Per Capita Income.

Figure 6 Real Per Capita Incomes Adjusted for Cost-of-Living Cost-of-living adjusted Real Per Capita Incomes in Ohio and the Cincinnati, Cleveland, Columbus, and Toledo Metropolitan Areas are above the National Average Per Capita Income.

In all cases, real per capita income in Ohio and these four metropolitan areas are higher than the U.S. average after accounting for regional cost-of-living differences. This is true because:

- In all cases, in all years, the Regional Parity index is less than 100.0 in the state and the regions.

- Unadjusted real per capita incomes are higher than the national average in all years in the Cleveland and Cincinnati metropolitan areas and from 2011 to 2017 and 2020 for the Columbus metro.

- Because the regional cost of living is lower in Ohio and all its metropolitan areas than the U.S. average, the purchasing power of average incomes in Ohio and its regions is higher than the U.S. average.

- The combination of lower-than-U.S. average cost of living and higher-than-U.S. average incomes in the Cincinnati and Cleveland metro areas, and frequently in the Columbus region, results in much higher purchasing power. Regional cost of living adjusted average incomes are 10.1% higher than the U.S. average in the Cleveland region and 12.5% higher in metro Cincinnati.

The important aggregate comparative outcome measure from economic development is the real income generated from the outputs of economic development activity, which is the sales of goods and services from the region’s traded sector. These charts demonstrate that Ohio’s residents secure a better quality of life than the average American despite having slightly lower average incomes. The bottom line: Cost of living matters when considering economic development outcomes.

Lessons for Site Selectors

Ohio is a portfolio state made up of at least seven regional economies based on labor markets: Cincinnati CSA, Cleveland-Akron-Lorain CSA, Columbus MSA, Dayton MSA, Mahoning Valley (Youngstown-Warren), Toledo, and the emerging networked labor market region of North Central Ohio. Each region has broad product and industry portfolios that form its tradeable sectors, and all are connected by productive farmland. Destination living is a traded industry along the Lakeshore and in the parts of Appalachia that abut the three-C corridor. Ohio is a complicated place.

Governor DeWine and Lieutenant Governor Husted have championed meaningful regional sector-led workforce training efforts to respond to the workforce shortages. The state’s higher education system increasingly embraces experiential education to produce a work-ready talent pool. The University of Cincinnati pioneered co-op education. The Ohio State University started experiential bachelor’s degree programs in engineering technology on its four regional campuses and at its Agricultural Technical Institute in Wooster. The University of Dayton, Ohio Northern University and Youngstown State University embrace co-op education and engineering technology.

These data show that Ohio’s economy is evolving, and employers are responding to its cost-of-living advantage and access to North American markets to evolve the state’s regional economies. Demographic realities are prodding the state’s regional labor markets to respond to in-state and regional migration. Development of Ohio’s traded sector will follow five paths.

- First, encourage shifts in the composition of its portfolio of traded products, moving to higher-value-added products and services.

- Second, the transportation sector is migrating to electrified vehicles.

- Third, export services providers are starting their digital journey as artificial intelligence begins to reshape back offices with AI.

- Fourth, Ohio is now adding amenity-driven destination living to its traded products and services portfolio.

- Fifth, the state has begun to respond to employers’ demands for a workforce that has benefited from experiential educational opportunities.

Dr. Edward (Ned) Hill is a Professor of Economic Development at the John Glenn College of Public Affairs and City and Regional Planning at The Ohio State University and a Senior Research Associate at the Ohio Manufacturing Institute.