I s it just coincidence that companies are realizing pioneering renewable energy success along Great Lakes shorelines? Or that territories in two nations are seeing progressive energy policies blend with their industrial heritage to spawn growth in corporate investment?

Sometimes corporate and regional growth strategies come together on common ground, such as a century-old steel plant site.

Lackawanna, N.Y., a town of just over 17,000 people that’s part of Greater Buffalo, was literally created as a steel town in March 1909. At one time there were some 25,000 people employed there, says former Mayor Norman Polanski in a film produced by Massachusetts-based wind energy developer First Wind. “The town sort of grew up around that steel plant,” remembers resident Jim Burke, referring to Bethlehem Steel’s enormous operation on the shore of Lake Erie.

Now a 30-acre (12-hectare) portion of that 1,100-acre (445-hectare) site, currently owned by ArcelorMittal, is home to First Wind’s 35-MW Steel Winds wind power farm, which just celebrated completion of phase two. The project will have the capacity to generate enough electricity to power approximately 9,000 New York homes,” said a company press release, “and help bring the state closer to its goal of 30 percent renewable energy sources by 2015.”

Burke says in the film that the project has rid the town of “one of the dirtiest neighbors we ever had,” and replaced it with something a whole lot cleaner — turbines that former mayor Polanski calls “gentle giants,” planted right at the shoreline, their towers licked by the waves.

Overlooked treasure is part of the town’s heritage. Its most famous landmark outside of steel is the Our Lady of Victory Basilica and National Shrine, one of only two North American Catholic churches so designated by papal decree, which earned the honor in 1926. Legend has it that the sanctuary’s four columns of rare red marble came about when some World War I servicemen from Buffalo stumbled across the material on a farm in Spain, and were able to convince the farmer to give what he termed “useless rock” to the church-building effort back home.

The area attracted freight yards in the 1800s from several railroads looking to avoid rail congestion in Buffalo. A federally funded breakwall along the lakeshore helped attract the Lackawanna Iron & Steel Co. of Scranton, Pa., to construct a new plant starting in 1900. What began as a $60-million venture blossomed into a giant mega-industrial complex with its own ship canal and other infrastructure.

After closing in 1983, the mill complex sat idle for 30 years, as the town’s population dropped by 30 percent, according to an EPA summary of the site’s brownfield history and redevelopment. Due to steel slag and industrial waste contamination, in May 2002, EPA awarded the City of Lackawanna a $200,000 Brownfield Assessment grant to investigate contamination at various properties in the city, including the mill. “Once the assessment was completed, the steel mill was chosen as a prime property for wind energy redevelopment because much of the construction could occur without excavating the contaminated soil,” says the EPA. “Instead, the windmill foundations, service roads and green space cover the contamination.”

Steel Winds got its start in 2006 after an agreement was reached between the cities of Hamburg and Lackawanna and First Wind. Phase I, at 20 MW, got started in June 2007.

“Fifty years ago Western New York set ourselves apart by taking advantage of our natural resources and building the Niagara Power Project,” said U.S. Rep. Brian Higgins at the Steel Winds completion ceremony on Feb. 21. “Today, with the addition and expansion of Steel Winds we again demonstrate our ability to embrace the region’s unique characteristics and harness the power of the wind to create clean energy. Here, on land at the water’s edge that has sat dormant for too long, we again have people working as we take what was old and make it new again to build a stronger tomorrow.”

The Steel Winds project, which created 100 jobs during construction, received significant tax breaks, but will contribute an average of $190,000 in annual tax revenue (approximately $13,571 per turbine) to the surrounding communities and school districts. First Wind also makes $100,000 annual voluntary payments to the cities of Hamburg and Lackawanna’s general funds. The total capital investment in the project is estimated at around $65 million — just above the total capital investment in the original steelmaking company established in 1900.

The First Winds project only occupies a small sliver of the overall Superfund site, most of which is located in the Bethlehem Redevelopment Area. What’s happening with the remainder? In November, the EPA and NREL announced plans to invest $1 million in studying 26 Superfund, brownfields, and former landfill and mining sites in 20 states for feasible development of renewable energy production. Those 26 include, once again, Lackawanna and its “Arcelor Mittal Tecumseh Redevelopment Inc. Property.”

Analysis will determine the best renewable energy technology for the site, the optimal location for placement of the renewable energy technology on the site, potential energy generating capacity, the return on the investment, and the economic feasibility of the renewable energy projects.

Ralph Miranda, director of economic development for the City of Lackawanna, says he applied for the EPA grant in order to now turn the EPA’s attention toward solar energy as well as wind — and not just for the electricity.

“We’re looking at two things — the manufacturing of the solar panels, and putting the panels out there and generating the energy,” says Miranda, who characterizes the site as more like 1,900 acres (770 hectares). An EPA spokesperson says Steel Winds is located on the parcel now being studied, but that the study is only looking at the technical feasibility for siting solar power generation facilities, not solar industry manufacturing and supply chain operations. Asked if EPA’s overall study is taking into account the nascent trend of co-locating wind and solar power generation on the same parcel (as GE has done in Illinois,) EPA responds that the agency “is only able to conduct a feasibility study for one technology.”

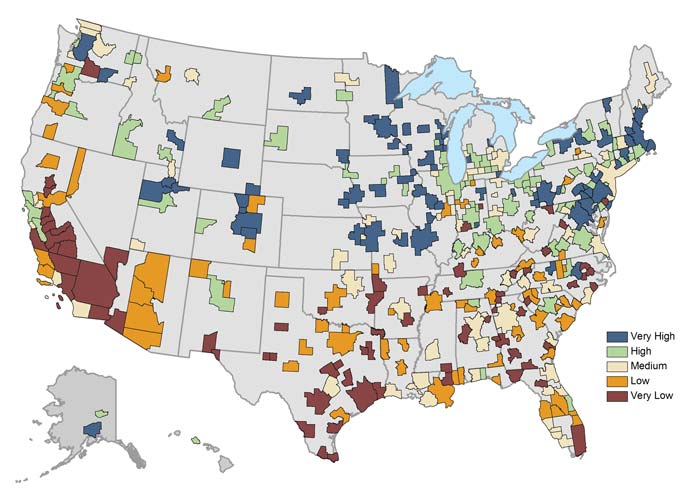

While the Great Lakes have few brownfield sites with the potential to generate utility-scale wind power, an EPA map showing sites with community wind potential (in the wind power class of at least 300 watts generated per sq. meter) shows 16 sites along Great Lakes shorelines. New York and Illinois in particular show “healthy” profiles for community wind.

The Bounce-Back Factor

There are reasons for such resilience in the Great Lakes. Several of them are found folded into the methodology behind the Resilience Capacity Index (RCI) developed by Kathryn Foster, PhD, director of the University at Buffalo Regional Institute (UBRI), and associate director, Building Resilient Regions Network, Institute of Government Studies, University of California, Berkeley.

The RCI is a single statistic summarizing a region’s score on 12 equally weighted indicators — four indicators in each of three dimensions encompassing Regional Economic, Socio-Demographic, and Community Connectivity attributes.

Foster developed the index as part of Building Resilient Regions, a national network of experts on metropolitan regions (visit http://brr.berkeley.edu). The index features maps revealing geographic patterns in resilience capacity, detailed data profiles for each metro and a “compare metros” tool.

“Overall, Northeastern and Midwestern regions tend to be more resilient than those in the South or West,” said a news release issued with the latest version of the index in July 2011, “largely because these regions earn high scores for affordability, the size of their health-insured population, rates of homeownership and metropolitan stability, as measured by recent population change. For instance, the Buffalo Niagara metro region ranks among the nation’s top regions for its metropolitan stability and health-insured population. However, lower rankings on indicators such as income equality, business environment and population without disabilities to some degree offset its assets. This gives the Buffalo Niagara metro region an overall RCI rank of 86, still categorized as high.”

Rachel Teaman, spokesperson for the University at Buffalo Regional Institute, says, “The region as a whole is really turning a corner in terms of economic development, breaking down silos, and regional planning toward sustainable development.” She lists several highlights, all of which have engaged the UBRI and The Urban Design Project (UDP) of the UB School of Architecture and Planning to provide research, public engagement and plan development support. Among them:

The Western New York Regional Economic Development Council submitted a strategic plan to the governor last November, which won “Best Plan Award” and brought home $100.3 million for the region. UBRI and the UDP provided major support on this effort, and the same team, working with the Brookings Institution, is now playing a key role in the development of a “Buffalo Investment Plan” for Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s pledge earlier this year to invest $1 billion in Buffalo.

“In one of the most significant steps forward for regional planning in Buffalo Niagara in decades,” writes Teaman, “a $2-million HUD Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grant was awarded to a consortium of public sector and nonprofit partners from Erie and Niagara counties to develop a plan that supports affordable, economically vital and sustainable communities. Over the next three years, UBRI and the UDP will work with such regional entities as the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority and the Greater Buffalo-Niagara Regional Transportation Council to develop planning, communications and technical assistance tools focused on housing, food systems and climate action, together comprising a regional plan for sustainable development.”

The City of Buffalo has initiated the first rewrite of the city’s zoning ordinance since 1953. The “Buffalo Green Code” is a place-based economic development strategy that will reinforce mixed-use development, walkability and environmental and economic sustainability. The five-county WNY region has also secured a major grant from the New York State Energy Research & Development Authority (NYSERDA) Clean Communities Program to develop a “WNY Sustainability Plan,” led by the environmental consulting firm Ecology & Environment.

Asked to what extent cross-border assets and resources are dovetailing to support economic development and corporate facility location in the renewable energy and cleantech sectors, Kathryn Friedman, research associate professor of law and policy and director of Cross-Border and International Research at the University at Buffalo Regional Institute, says there is nothing solidly in place yet, “but people are taking a serious look at leveraging our border location in two ways: enhancing our logistics infrastructure to better facilitate trade flows in innovative industries, and actually creating the enabling environment for those innovative industries to thrive in Buffalo.”