Louise Story’s article in The New York Times last month is merely the latest installment of the longstanding observation that state and local incentives amount to a zero-sum game, whereby one location’s win is another’s loss. But there is an important and often overlooked value in this type of inter-governmental competition. That is, that state and local governments are forced to provide an attractive mix of taxes, services and infrastructure, or businesses will “vote with their feet.” I served on the economic development staff of New York City at a time when company after company was leaving for lower cost locales (particularly lower tax costs) in the Sunbelt. The only thing that prevented the total exodus of the city’s business tax base at the time was a series of new tax incentive programs and general business tax reforms that reduced the overall business cost disadvantages of New York for “footloose” companies — those making relocation decisions.

One important consequence of our federal form of government is the right of taxation that is left to individual states. From the state level our nation’s strong tradition of “home rule” further devolves the right of taxation onto our local governments. With every unit of general state and local government having independent taxing powers over business, there is going to be a natural competition that pits communities against their neighbors in vying for a limited business tax base. Differential tax rates and bases, and myriad tax and non-tax incentives have been a reality in the U.S. for centuries, and my guess is they will be so for a long time to come.

This article is intended to assist companies in navigating this competitive and ever-changing landscape and in maximizing the ROI from their capital investments.

As your company prepares its capital budget, it will be presented with an excellent opportunity to boost ROI by maximizing state and local incentives. Some companies are prepared to exploit these opportunities, while others will merely go through the usual motions of ranking alternative investments by internal ROI and other internal measures without any consideration of potential incentives.

If you want your company to be among those “mining their own business” for incentives cost savings, I have found that there are three critical steps to success in maximizing capital-related discretionary business incentives.

Step 1: Gather Relevant Data From Across the Business Units

This is the step that trips up most companies, especially the big ones. Most often, the problem is that the tax department or other incentives-responsible staff doesn’t own enough of the capital budgeting process to be brought into the loop when all of the capital requests are still on the table. They are usually informed after the final decisions have been made. The tax director is told, “Here is the capital budget for next year. The Board is announcing the key elements in our year-end filings and the business units already know. Make the best of it.”

A more proactive approach needs to be followed if incentives are going to be maximized. The “best practice” in accomplishing Step 1 we have seen is when the incentives-responsible staff periodically surveys the business units for their upcoming capital requests before those requests are approved by the Board.

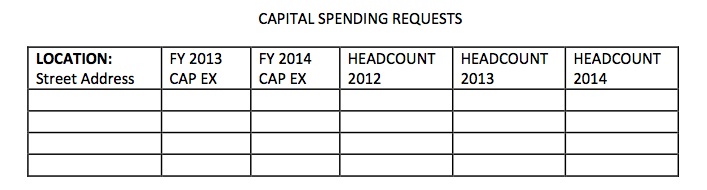

It is important to note that there are very few discretionary incentives that are awarded without regard to the investment’s impacts on headcount. Therefore, the business units are going to need to supply the staffing plan by location as well as the capital spending data. That’s not to say that a planned reduction in headcount will necessarily disqualify an investment for government incentives, but simply that headcount, per se, needs to be known and presented along with the capital investment information. To that end, we typically suggest a simple table of CAPITAL REQUESTS and corresponding headcounts be compiled in the following format from each business unit:

Obviously this data set does not contain everything we are going to need to estimate the return on investment from incentives, let alone to actually go after those incentives that are significant enough. But what it will do, in effect, is serve as an “80-20 filter” — that is, we will be able to identify which 20 percent of the company’s investments are going to produce 80 percent or more of total potential incentives value. To carry on the mining analogy, we will know where we should dig deeper.

In some cases, this first step is the most difficult. In highly decentralized companies, getting the business units to buy into the process can be very difficult for two reasons: First, many of these decentralized companies effectively allow the business units (BUs) to set their own capital budgets. Internal tax or real estate departments may not be notified until the BUs have finally decided on capital items for the coming year, and they are already announced internally to the locations that are getting the investments. Second, often the incentives’ value is fully absorbed at the HQ level (this is the case for many companies with discretionary state income tax credits) and not passed along to the BUs. How then does one get the BUs to buy into the process?

The best approach we have seen to motivate the business units to assist in capturing incentives whose value will not go directly to the BUs’ bottom lines is to peg a portion of the unit’s annual bonuses to financial measures that include the award of incentives from governmental entities in return for their BU’s projects. Alternatively, the CFO can use his influence with the BUs to force compliance with an incentives capture process.

Enlisting the CFO to exert his/her influence can be simply a matter of presenting the incentives successes of your company’s competitors. For that, we maintain a new proprietary database showing the more than 6,000 announced discretionary incentives packages that have been awarded since 2010 across the U.S. Once they see the history of sizable incentive awards to their competitors in states they are planning to invest in, the CFOs become staunch advocates for maximizing the company’s capital-related incentives.

But even in highly centralized companies, it can be difficult to access the right information in a timely manner. We had one client recently — a tax director of a highly centralized service-sector company — who simply could not access the necessary future headcount or capital expenditure data for more than a year and a half. During that period several years of refundable income tax credits were lost, as their statutes of limitation were reached.

The following table is an actual result from a company we worked with last year. You can see how easy it is to spot significant potential incentives opportunities from this brief data set.

Step 2: Re-Define Projects To Satisfy the Governments’ Definitions

Projects, as the business units define them for capital budgeting purposes, are not the same as the economic development “projects” the government supports with incentives. This is a critical distinction.

For example, let’s assume two scenarios in the same location are about to play out. First, a capital project (as the business defines it) intended to boost productivity in a particular manufacturing process will enable a reduction in headcount devoted to that process. Six months later, a production line is expected to be moved in that would add heads without any significant capital spent on new equipment. When each is viewed separately through the eyes of the government economic developer, they may both fail to qualify for investment tax credits or other discretionary incentives. But taken together, under the umbrella definition of a “production increase and plant modernization project,” as the government defines a “project,” these same programs will hit all the triggers for significant discretionary incentives. So, the story given to the government authorities is quite different than the ones heard by the company’s board of directors in justifying the capital expenditures individually.

Another example of defining a project to suit government incentives definitions is to aggregate routine capital maintenance costs over time with other capital costs in the same location. Most state and local discretionary programs allow a two- or three-year window to achieve investment goals. But a company might prepare a location for a piece of machinery in, say, Q1 2013, install the equipment in Q2 and be operational by June of 2013. Then, it will go on to spend another amount in June of 2014 and 2015 to replace parts and perform maintenance. The installation costs as well as the expenditures in 2014 and 2015 can usually be counted along with the equipment costs in qualifying for incentives. In some cases, even soft costs for relocating equipment and training employees to use it can be considered part of the expenditure that qualifies the investment for incentives.

The process of matching up capital projects with headcount changes and aggregating capital and capital-related costs within a state can reveal numerous opportunities for discretionary incentives that do not appear otherwise.

Clearly, the most powerful integration of planning data for incentives purposes comes when we combine the staffing plan with the capital plan. That’s why we explicitly cover headcount in Step 1 data gathering.

Absolutely key to this part of the process is knowledge of the government incentive programs in the investment locations and what constitutes a “project” under each program. Every discretionary incentive program has its own unique definitions. The following is a list of common eligibility questions that will have to be answered by incentives-responsible staff:

- How long do we have to hire eligible employees and to spend the promised capital?

- Will work we did on the facility last year to prepare for the new line count toward the minimum investment threshold?

- Do retained heads count?

- Can investments in multiple locations within a state be combined?

- Are installation costs and maintenance expenses in year two and three able to be included?

- Is relocated equipment eligible? If so, at what level? (New cost less depreciation?)

- How about the cost of equipment relocation? Or relocation of personnel?

- Is there a minimum wage level for new jobs to be counted toward eligibility?

- Do new hires’ health plans need to be paid in part by the company in order to qualify them for the incentive program?

- If training costs are incurred out-of-state, can they be reimbursed?

Once you are armed with answers to these kinds of questions, you can go back to the capex list and piece together the “projects” that will enable the company to maximize its incentives in a given location.

How the re-defined projects are presented to the competing governments is important as well. We routinely provide a rigorous, independent input-output based, economic and fiscal impact study that demonstrates how the community will benefit from the “project” as re-defined. These studies utilize well-established econometric methods to estimate the indirect impacts of the company’s project on jobs, household incomes, gross product and even state and local tax receipts. If and when the time comes, the government officials can use this study to justify the incentives package to the general public.

Step 3: Create and Maintain a Competitive Environment

Obviously, governments are only motivated to offer discretionary business incentives when they believe they are competing with other jurisdictions for the company’s projects. The model we like to emulate is that of an auction environment. The governments understand that companies have alternatives. They will use incentives as a way to distinguish their “bid” for your company’s projects.

As with any auction, time works for the seller. The more time bidders are given to think it over, or to find creative ways to finance their purchases, the higher the bids will go. It’s no different with discretionary incentives. And bear in mind, you have government bureaucracies as competing bidders, and they are notoriously slow to reach decisions. So commencing the dialogue with government authorities should occur as soon as possible after the capital project requests are assembled.

More often than not, companies defer their initial approach to government until after the internal investment decisions are made, for any or all of the following reasons:

- Confidentiality: The thinking is that government cannot be trusted with sensitive forward- looking information;

- Unfulfilled expectations: Since the company will only invest in four out of the 10 projects “in the hopper” this year, “we shouldn’t raise false hopes” in the other six locations;

- Wasted effort: Opening a dialogue in 10 locations would be wasteful if the company is going to invest in only four.

But experience has shown that each of these reasons is flawed:

- Confidentiality: Government economic development staffs are highly trained in maintaining trade secrets of their client companies. In addition, if outside consultants are engaged to assist the company, they can approach the government on the company’s behalf on an anonymous basis, at least through the preliminary offer stage of the dialogue.

- Unfulfilled expectations: Government economic development agencies are established for the express purpose of affecting corporate investment decisions. They are eager to learn of every opportunity to attract an investment, even if their chances are remote. Their worst fear is that decisions will be made to invest outside their jurisdictions without them getting a chance to compete. They are also prepared to lose more competitions than they win.

- Wasted effort: Most governments require a “but for” affirmation by the company as part of the discretionary incentive award process. That means the company will need to state that the incentive influenced its decision to move forward in that community. Opening a dialogue in several competing locations is an excellent way to support the “but for” affirmation, and is therefore in no way a waste of effort.

Once the internal decision is made on the specific capital investment, there is usually a window of several months before construction or hiring occurs or new equipment is placed in service. It is crucial that during this period, the “last-best” offers of incentives from each competing governmental unit are received, analyzed and fully negotiated.

An important challenge during this period is controlling the company’s internal and external communications. If the investment is announced by the company as definite prior to the last-best offer, the government will usually pull most of the incentives off the table. In order to avoid such pitfalls, the company’s communication plan must be synchronized with the government incentive program’s approval process. Only then can the company be certain to maintain a competitive environment for as long as necessary to maximize the incentives.