Featured in the Montreal Neurological Institute and Hospital’s "Neuro XXceptional" series of videos celebrating exceptional women scientists and clinicians, Nguyen-Vi Mohamed says in the sweetest of voices, "My name is Vi [pronounced ‘vee’] and I make human mini-brain from blood of patient," before switching over to French to tell her story:

"When I arrived here in Montreal," she says, "I opened two bakeries. I am also a scientist. If you are a good baker, you can be a good researcher."

Back in English, she makes another comparison: "Mini brains are like babies. You need to feed them every day. They need a lot of attention and love also. Students often ask me if mini brains have consciousness. I always say it depends on what their definition of consciousness is. Is it electrical signals? Because yes, the nerve cells in mini brains do communicate via electrical signals."

French: "The environments of bakeries and laboratories are very similar. There are incubators in one instance, and cell culture chambers in the other. We do exactly the same work. We control the temperature, humidity, pressure, and in this way, we can propagate life."

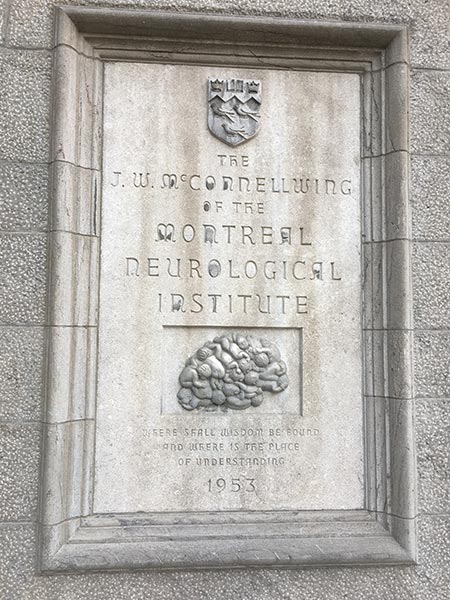

This spring I met Vi and her colleagues during a tour of "The Neuro," the nickname of the legendary center, part of McGill University, next to the now-vacated site of the 125-year-old Royal Victoria Hospital on Mount Royal.

Viviane Poupon, PhD, executive director, partnerships and strategic initiatives at The Neuro, says the unique institution pursues both an academic and clinical mission. That’s immediately evident as clinicians and scientists bustle from hallway to hallway as patients ranging across the entire range of ailments enter and leave the 80-year-old building.

"We embed trials in clinical care," explains Dr. Angela Genge, director of the Neuro’s Clinical Research Unit (CRU) and ALS clinic. Tuesday is brain tumors. Tuesday afternoon is epilepsy. Friday is Parkinson’s movement disorders. ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease), multiple sclerosis and neuro-oncology are among nine tertiary care programs at the site. The CRU at McGill performs 15 percent of all neurological clinical trials in Canada — about 100 trials running in parallel. "We didn’t realize it was that much," Poupon says, "until the industry told us."

Key to the enterprise is a biobank with around 600 patient samples. "The biobank will be a major part of corporate partnerships — imaging, potential muscle biopsies. All will have iPSCs [induced pluripotent stem cells] grown up and phenotyped. That becomes something the corporate partner works with us on. There’s a finite amount of brain tumor tissue, vs. iPSCs, which can keep going."

As for the clinical work itself, also important is the generous mindset of patients and their families. Asked how those patients approach it, Poupon says there is an eagerness to participate.

"It’s a legacy to the next generation," she says. "When you have ALS, you know that within two to five years you’re dead — it’s blunt but true. You want to contribute. They really see a value. And in the open science context, they don’t see a conflict. Their sample can be used, even if they’re not there anymore. They appreciate that factor. The patient can say, ‘I’m doing something, maybe not for me, but in five to 10 years when you have a treatment, I will have done something.’ This is what drives everything."

"A lot of patients want to have a long-lasting contribution," says Thomas Durcan, an assistant professor in the department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill University and a member of the Centre for Neurodegenerative disease group at the Neuro. "When you have these diseases, there are no cures. They want to see a cure."

Open Book

The biobank become even more powerful when combined with the Neuro’s recent decision to become an open science institution. The commitment took concrete form with the dedication of the $20-million Tanenbaum Open Science Institute in December 2016 with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau presiding. Its mission is to develop and spread a new model of discovery and innovation based on open science principles as accelerators.

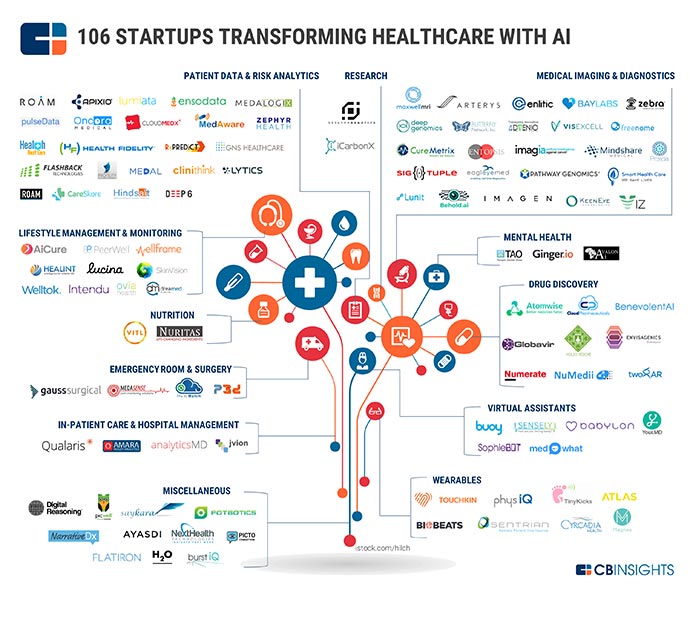

"If you generate that much data, you can’t be the only one to use it," says Poupon. "What we would hope as an outcome is we don’t speak about Parkinson’s as a disease, but as 10 categories of Parkinson’s. We’re fortunate that Montreal is becoming a major hub for artificial intelligence. Our job is to collect the data, cluster them in a neuroinformatic platform, and work with partners."

The Neuro’s work with Takeda and GSK on an ALS project is a case in point. With more than $16 million in funding since 2015, the model involving around 300 patients a year is being developed in an open space, available to anyone who wants to use it. For a Parkinson’s project, samples are being collected from around 5,000 patients across the province.

One of the Neuro’s best partnership examples is its work with Biogen.

"I first worked with them in 1995, when they were a small emerging biotech turning into a small pharma," Genge says of their early work on drugs to treat MS. Over more than 20 years since, the Neuro has worked with the company on 15 to 20 programs, including a current one focused on therapies for spinal muscular atrophy. Biogen’s CEO was expected to visit in May in order to discuss partnering on the biobank side, using the Neuro’s specimens for their R&D work.

"It started with a relationship 25 years ago, and now it’s maturing into an outsourced preclinical and clinical partnership," Genge says, noting that this is one case where company location might not be ideal, at least for the Neuro. "We’re hoping that they don’t establish a lab in the area, but partner with Neuro, and the lab, as part of their job, will run the experiments that are needed."

She says the next few years will see a big explosion in gene therapies for rare neurological diseases, with increasing work on the stem cell.

"There are a lot of gene modification technologies being worked on — that’s one of our strong suits," she says of the 35-person CRU. "We’re going to hit 110 trials by the summer."

A Love Story

That sort of work is attracting talent and rejuvenating the institution, as it has welcomed 18 new young faculty members, like Vi, in the past three years.

Who is Vi? The Vietnamese-Canadian scientist fills me in:

"In 2009, I did an international exchange for my Master’s in Montreal," she says. "I decided to specialize in neurosciences. During that year, I literally felt in love with Montreal, its city vibes and its sciences vibes. I had that strong feeling that everything would be possible here because there is an incredible dynamism between people. So I came back to France for one year in order to finish my Master’s and also ‘pack up’ my husband with me. It was a crazy idea, because he was lawyer in Paris at that moment, running his own successful business in law.

"Maybe because he wasn’t that happy with his stressful law life, he decided to sell his 15-year-old law firm and crossed the ocean with me," she writes, in a reverse of the usual narrative where lovers run away to Paris.

Her husband, Frédéric Mac Guire, had been enrolled in classes in Paris in order to become a baker — a goal that in France is somewhat akin to deciding to learn baseball in the Dominican Republic, where the propensity seems bred into the genes.

Montreal has its share of fine bakeries too, but perhaps a bit more of an opening for an enterprising second career dreamer.

"Arrived in Montreal in 2011, we worked on the French bakery project for almost a year before opening the first shop in 2012," the baker’s scientist wife explains in an email. "I was doing my PhD during the day, and my baker life during the night … We were so enthusiastic and forgot to sleep for almost a year. We were growing the bakery, the PhD projects, all together with the energy of new parents who take care of newborn babies."

Ultimately the mini-brain work of Nguyen-Vi Mohamed might have a direct bearing on the full-sized brains around the world. Durcan calls Vi "one of the exceptional leaders of Neuro — she runs a bakery, and makes mini-brains on the side.

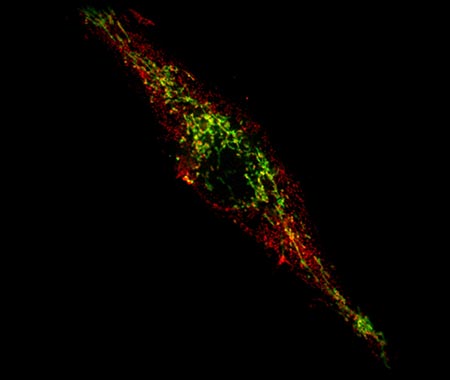

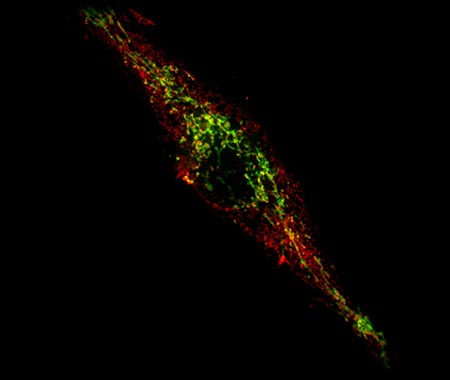

A mini brain is literally a mini model of the human brain that measures 4 millimeters across and is made from patients’ cells reprogrammed into stem cells, she explains to me. "I implemented the mini brain model at The Neuro in order to be able to study the pathological mechanisms of Parkinson’s disease. My long-term goal is to further develop the model so that it can be a platform to discover new therapeutic molecules."

Ultimately, however, that quest is tied up with another that she explains in that Neuro video: "I started to work on the brain because I was fascinated by this organ which defines what you are."

Today the Boulangerie Chez Fred, her husband’s business, is a pastry and bread lover’s destination. Meanwhile, Vi has found Montreal a destination worth much more than a visit. She completed her PhD on Alzheimer’s disease, at the CRCHUM, the French side of the Montreal Neurosciences Institute. "Then for my postdoc I joined The Neuro because I think this is the best place in Canada for iPSCs technology and Parkinson’s disease investigations, thanks to Dr Fon," she says. That’s Dr. Edward Fon, a full Professor in the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill University and the scientific director of The Neuro.

Durcan originally joined Fon’s Parkinson’s research group when he was doing his postdoctoral research. Like Vi, he came from away, arriving from Ireland around 11 years ago.

"The greatest thing about Montreal is how international it is," says the proud dual citizen, noting that his own lab has professionals in it from China, India, Quebec and France. Iranian and Mexican grad students are on the way. Vi says the multicultural vibe is even strong in the culture room (as in cell culture) itself: "There is one hood where people speak Chinese, another hood where they speak French, and then in the middle they speak English," she says.

"I like living and working here because this is a city for entrepreneurs and this is one of the top cities for neurosciences," she says. "All combined, it was very clear for me that Montreal and The Neuro will give me huge opportunities to achieve my projects as a young woman neuroscientist and entrepreneur."