P |

fizer’s 600-employee expansion in Ann Arbor, Mich., looked deceptively simple — on paper, at least, once it was a done deal.

One number fairly leaps out in the postmortem: a whopping US$84.2 million in incentives, certainly enough to vacuum-seal most major expansions.

And those bountiful incentives certainly did help seal this $600 million to $800 million deal. But it wasn’t all that simple in putting together one of 2001’s most high-profile corporate location projects.

All the incentives in the world, after all, don’t count for much without a suitable site. And that was something Pfizer sought in vain in Ann Arbor in the early stages of its search.

“The main challenge was that the land that surrounded the Pfizer Ann Arbor Lab was owned by the University of Michigan (UM), and we didn’t know if that could be available,” says company spokeswoman Betsy Raymond. “So the only option would’ve been to get land that was not adjacent to the existing lab.”

A non-adjacent site would’ve been big trouble. Big enough, in fact, that it would’ve meant uprooting Pfizer’s entire 3,100-employee Ann Arbor operation.

“[A non-adjacent site] would’ve been a real problem in drug research,” Raymond explains. “Scientists wouldn’t have run into each other during the day and exchanged ideas. Down the road, that would’ve meant that we would’ve had to look for a new site and eventually relocate all of the lab so we could keep everyone together.”

Ann Arbor Site Overcrowded

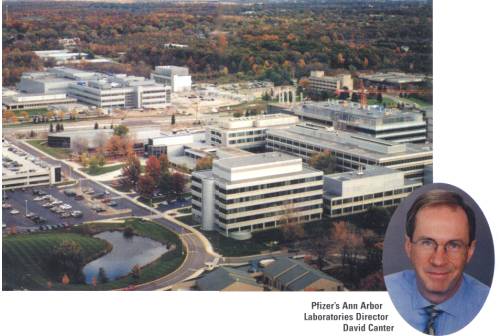

Further expansion was impossible, though, at Pfizer’s 92-acre (37-hectare) complex near UM’s North Campus. The built-out Ann Arbor Laboratories site was so overcrowded that 800 employees were housed at five off-campus sites.

That overcrowding reflected Pfizer’s success in Ann Arbor, where it was the city’s largest private employer and taxpayer. Since 1960, employment at the company’s site had increased 10-fold.

That growth, company officials acknowledged, reflected a host of pluses in Ann Arbor. Pfizer was keen on the state’s life sciences research institutions and its established Ann Arbor base, which developed the cholesterol-lowering drug Lipitor. In addition, Pfizer liked its success in Ann Arbor in attracting and retaining high-tech employees.

Something, though, had to give. Overcrowding plus the lack of a suitable site made for a potent one-two punch. Potent enough that Pfizer began investigating expanding at one of its six other worldwide research centers in Asia, Europe and the United States.

The major contender was reportedly New London, Conn., headquarters not only for Pfizer, but for its research division as well.

Adjacent UM Site Goes to Market

Ann Arbor’s prospects looked dim. Then, though, Ann Arbor Laboratories Director David Canter decided to approach UM officials. Would selling some of its land to Pfizer, Canter asked, be a possibility?

UM officials mulled over the prospect. The university owned a vacant 55-acre (22-hectare) tract adjacent to Pfizer’s complex. The property was generating no tax revenues.

Selling the plot to Pfizer, UM leaders decided, could set the stage for a win for town as well as gown. In late September, the university’s Board of Regents unanimously approved a tentative deal to sell the acreage to Pfizer for some $27 million.

Executive Vice President and CFO Robert Kasdin, UM’s point man in the land sale, called Pfizer’s expanding in Ann Arbor “critically important to the company, the university’s commitment to life sciences and the community’s continued economic health.”

Incentives and Cost-Effectiveness

Finding that elusive site, however, didn’t seal the deal. Now it came down to incentives.

“Pfizer can grow at any one of our worldwide labs,” Raymond explained. “We go where it’s most cost-effective.” Only with incentives would Ann Arbor rank as the most cost-effective option, she said.

Clearly, major state incentives were in the offing. Michigan officials considered Pfizer’s expansion a keystone in enlarging the state’s life sciences cluster. Led by Gov. John Engler, the state Legislature had created the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor in 1999. And Michigan was backing the initiative with a $1 billion, 20-year investment.

But another incentive shoe had to drop first: State subsidies were contingent on the city’s response to Pfizer’s application for a property tax abatement.

That response came on Nov. 19, 55 days after UM agreed to the land sale: The Ann Arbor City Council approved a 12-year abatement valued at $47.7 million.

Dominoes in Rapid-Fire Fall

That set the rest of the dominoes to falling in rapid-fire fashion.

The next morning, Engler and the Michigan Economic Development Corp. brought their part of the incentive pie to a full bake. The state awarded Pfizer a 20-year credit on the Single Business Tax worth an estimated $25.8 million, plus a 12-year abatement of the six-mill State Education Tax, valued at $10.7 million.

Pfizer quickly followed suit, committing to the Ann Arbor expansion on the same day.

The slam-bang series of events left everyone a winner, Canter asserted.

“This is a win-win-win solution that will benefit the state, the city of Ann Arbor and Pfizer,” Canter said. “Pfizer now will have the land we need to flourish. This will bring the city of Ann Arbor and the state of Michigan economic growth and new jobs in the research and development sector, strengthening the Michigan Life Sciences Corridor initiative.”

Pfizer’s decision, said Engler, affirmed the state’s “vision of being one of the nation’s premier life sciences centers. This site is the nerve center of the Life Sciences Corridor extending from Detroit west to Grand Rapids.”

The corridor was also “a plus” for Pfizer, Raymond explained.

“If there are a lot of good, strong biotechs and academic research going on in the vicinity, that’s very stimulating,” she said. “There’s just a synergy in everyone being together and sharing research and having collaboration. The sum really is greater than its parts.”

Built-In Real Estate Investment

The deal includes major built-in real estate investment. Ann Arbor specifically structured its incentives to encourage new facilities, which, City Council members noted, would both create tax revenues and signal Pfizer’s commitment.

Ann Arbor’s incentives require the company to invest a minimum of $100 million in property within five years. If total investment reaches the best-case scenario of $800 million, Pfizer must invest at least $300 million in property.

Without supportive teamwork, however, Pfizer would’ve likely invested somewhere else.

Canter praised the “unprecedented collaboration” of a large private corporation, a public university, a Republican governor and Democratic mayor. “We have leaders who personally secured Pfizer’s future in Ann Arbor,” he added.

The teamwork was a two-way street, said Ann Arbor Mayor John Hieftje, a key player in securing the city’s incentives and persuading UM to sell its site.

“Pfizer was willing to work with us,” Hieftje noted. “They went the extra mile to provide a win-win situation. I don’t think we could ask for a better corporate citizen.”

Daniel O’Shea, vice president of operations and public affairs for Pfizer’s research division, perhaps best summed up the collaborative core at the heart of this deal.

Surveying the myriad players gathered for the project announcement, O’Shea noted, “I’m a dreamer in a room full of dreamers.”