What if the nearly sole supplier of a critical ingredient was about to cease operations? And what if that ingredient was critical to 20 million US medical testing procedures a year?

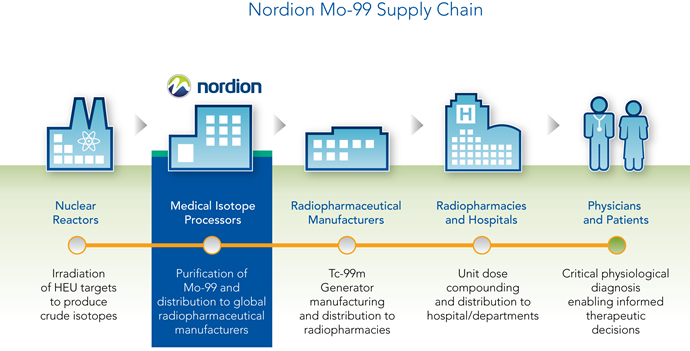

Such is the case with the radioisotope Molybdenum-99 (Mo-99), the basis for the most widely used medical isotope in the world, Technetium-99m (Tc-99m), which is used in approximately 40,000 medical diagnostic procedures per day in the United States. With its short half-life, the isotope needs to be used in patients very quickly after it is created.

Mo-99 is essential to 80 percent of 50 million nuclear medicine procedures worldwide. Between 40 percent and 80 percent of Mo-99 used in the US is sourced from one place: the National Research Universal reactor (NRU) at Chalk River, Ontario, Canada, opened in 1957 and operated by Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL).

In 2010 the Government of Canada announced its decision to cease the routine production of Mo-99 from the NRU in 2016, as the facility essentially reaches the end of its useful life. Since then the government has announced it will support the extension of the NRU operations until March 31, 2018, as Mo-99 consumers worldwide scramble to find a reliable supply. In 2012, the US Congress passed legislation making it a national priority to produce Mo-99, an isotope necessary to detect a wide range of diseases, including cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Coquí Pharma was way ahead of Congress. In 2010, the same year as the original Canadian announcement, the Puerto Rican medical isotope company, based in Coral Gables, Fla., started a site selection process for a facility to make Mo-99 and house its corporate and R&D functions. Working with design and consulting firm Gresham, Smith and Partners, the team evaluated the entire Southeastern US from Texas to North Carolina and all points south, says Kevin Tilbury, a planner with Gresham, Smith and Partners who has worked with the company from the beginning.

The team also includes DC-based law firm Hogan Lovells, which advises on Nuclear Regulatory Commission matters; Argentina’s INVAP, which designed a similar Open Pool Reactor facility for OPAL in Australia and will do the same for Coquí; and MPR Associates, which serves as owner’s rep and performs project management. Tilbury says around 100 people at his firm alone have touched the project over the past five years.

After issuing an RFI, the team narrowed its choices in 2011 to sites in Alachua, Fla.; Fort Pierce, Fla.; and Baton Rouge, La., and ultimately, in August 2014, announced Alachua’s Progress Corporate Park as its final choice. The University of Florida Foundation finalized its donation of the land in January. The company said last August the project will create 164 jobs (average wage $75,500) and generate a capital investment of approximately $230 million. The projected cost is now $339 million, and the projected job creation total has likewise risen to 200.

“They were all great locations,” says Tilbury, but Alachua County’s offering was set apart by a number of things, including Florida’s generous incentive package and the presence of a nuclear engineering program and a research reactor right across the street from where the Gators play football at the University of Florida in nearby Gainesville. “Coquí Radiopharmaceuticals provides the University of Florida with a valued regional partner in the areas of medical science and nuclear technology, said Dr. David Norton, vice president of research at the University of Florida. “We are very excited about their decision to locate here in Alachua County as it brings high-tech jobs and economic development to the area, in addition to supplying much needed medical isotopes to hospitals across the country.”

Also cinching the deal was an integrated community approach, with the city, county, university and the Gainesville Chamber’s Council for Economic Outreach presenting a unified and collaborative message. “That was a big positive for Coquí,” says Tilbury, noting in particular the proactive involvement of the mayor and assistant city manager for the City of Alachua. “They treat us like family.”

Family also played a role as the area courted Coquí. When the team first visited the park, their meetings were hosted (and continue to be hosted) by InterMed, a seller and supporter of X-ray, ultrasound and nuclear medicine equipment. InterMed founder Rick Staab’s son Tyler suffers from dystonia, a neurological movement disorder characterized by involuntary and sometimes painful muscle spasms and contractions. Staab and his wife Michelle launched the Tyler’s Hope Foundation to raise money for a cure for the disease, which also affects their daughter Samantha.

As it happens, the medical isotope Coquí is producing is intended to research, diagnose and help treat dystonia, among other maladies. A company, a community and a cause were already aligned.

“On behalf of my company InterMed Nuclear Medicine and our foundation, Tyler’s Hope for a Dystonia Cure, we welcome Coquí to our community and consider this announcement a huge and exciting success,” said Staab last August. “The decision to build the new facility here is great for our community, the United States and for all of healthcare. I have personal connections to many of the benefits of Coqui’s services, ranging from my father’s lifetime in nuclear medicine to family battles with dystonia and Alzheimer’s. Absolutely a great addition to our communities’ image as a world leader in medical research.”

This month, Gresham, Smith and Partners and Coquí announced the schematic design for the new 250,000-sq.-ft. (23,225-sq.-m.) facility was complete, with detailed design to follow. It encompasses a production side, including a research reactor, that is required to be a secure facility, as well as corporate offices and campus-style landscaping, all on a 25-acre (10-hectare) parcel that up to now has been sprouting cotton.

“Our designers had to segregate the two and yet integrate the design,” says Tilbury.

“Because of the many unique aspects of this facility, we have brought together a multi-disciplined team of architects, engineers, environmental scientists, interior designers and planners from GS&P’s Industrial, Environmental, Corporate + Urban Design and Land Planning markets,” said John Wharton, P.E., a senior vice president at Gresham, Smith and Partners whose portfolio includes work on at least comparable facilities in places such as Oak Ridge, Tenn., as well as past industrial projects for Alcoa in multiple states and abroad. “The design features a beautiful landscape, a stunning corporate headquarters, and a state-of-the-art production facility. We believe the project will be an inspiring, modern and sustainable landmark in Alachua that supports the company’s unique production needs with highly tailored process-driven design. Our team is proud to be part of such a worthwhile project.”

The design will ensure Coquí Pharma operates on a minimum energy consumption rate with limited carbon dioxide emissions by mitigating solar exposure and enhancing the control of daylight throughout the building. Water efficiency also played a pivotal role in the design process. The positioning of the structure also took into consideration two Heritage Oak trees that will essentially bookend the facility.

Next comes the technical investigation phase to meet the NRC’s requirements, a process that will culminate in an application to the NRC by the end of this year. The company hopes to complete the licensing and begin construction by 2017. And Coquí has conservatively estimated a 2020 time frame for commercial operation, says Tilbury.

That’s two years after the already-extended closure date of the Chalk River facility in Canada.

“We’d like to be operating sooner than that,” says Tilbury, “but that’s the conservative estimate.”

Desperate Race

There are other contenders to meet the expected need. Some are in more dependable locations than others.

INVAP has worked on more than 15 nuclear reactors and related facilities across the world, including several reactors used to produce medical isotopes. Among these is the OPAL reactor in Australia, the ETRR-2 reactor in Egypt, and the NUR reactor in Algeria. “There are some producers in Europe and Russia,” says Tilbury. “But for obvious reasons we don’t want to have to rely on Russian supply.”

The Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (DOE/NNSA) is working to develop a reliable and sustainable means of producing Mo-99 without using highly enriched uranium (HEU), including assistance to help convert Mo-99 producers to low enriched uranium (LEU). Its partners have included NorthStar Medical Radioisotopes, which is developing both neutron capture and accelerator-based technologies; and SHINE Medical Technologies, based in Wisconsin, which is developing accelerator technology with LEU fission.

NorthStar, based until now in Madison, Wis., last July broke ground in Beloit, Wis., for a new 50,000-sq.-ft. (4,645-sq.-m.) complex that will house its relocated corporate HQ and Mo-99 production facilities. The new facility is phase one in the planned development of a 32-acre (13-hectare) corporate campus for NorthStar. It will support the company’s work at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) in Columbia, Mo., where NorthStar is developing a neutron capture process to generate Mo-99.

Phase two of the campus development project would see the building expanded; the site could accommodate a building more than twice as large as the initial structure. Phase three would include construction of a linear accelerator facility for use in the second Mo-99-generation process that NorthStar is developing. A third building also could be constructed on the site in the future as the company continues to expand.

While independent of DOE/NNSA’s Mo-99 Program, “other projects are complementary to domestic and international efforts to ensure a reliable supply of Mo-99 produced without HEU,” said an NNSA release from November. “These groups include, but are not limited to:

- Coquí Radiopharmaceuticals

- Eden Radioisotopes

- Flibe Energy

- Niowave

- Northwest Medical Isotopes

- NuView

- PermaFix

In February, Sterigenics International LLC and Ottawa-based subsidiary Nordion announced agreements with General Atomics and MURR to establish a new, reliable supply of medical isotopes. Nordion pioneered the efforts to develop the first commercial supply of fission-based Mo-99, bringing it to market 40 years ago. The General Atomics TRIGA® is the most widely used research reactor in the world with 66 facilities in 23 countries on five continents. Nordion and its partners expect routine supply to begin in 2017.

But is it scalable?

Coquí calls its technology “the only proven, demonstrated, safe, and reliable method for commercially scalable Mo-99 production. Coquí Pharma’s facility shall fully comply with the Global Threat Reduction Initiative and shall emphasize safety. Our manufacturing process shares a history of FDA approval in the United States as opposed to potential competitors who must completely prove their experimental processes with the FDA and regulators. Other technologies, such as liquid reactors, are still too greenfield to be employed and accelerators based processes have a low production rate. That is why Coquí, using technology whose basic principles have been safely employed for decades, shall revolutionize the industry by being the first dedicated Medical Isotope Production Facility in the United States using state of the art LEU Mo-99 optimized procedures.”

Tilbury says some Mo-99 producer contenders have already fallen by the wayside. But by the time that Canadian reactor shuts down in 2018, all solutions on the table may be needed.

“The US gets 40 to 80 percent of its supply of Mo-99 from that reactor,” says Tilbury. When the shutdown occurs, he says, “You’ll hear about it more in the news, because there will be a gap between when that reactor goes offline and when domestic capability fires up.”