A few things have changed since the not-so-long-ago era of the million-square-foot warehouse and lines of ships waiting to get into ports. Those things begin with the recession, and don’t end with environmental concerns.

The Inland Empire warehouse market in California has rates hovering between $0.25 and $0.33 per sq. ft. among its 410 million sq. ft. (38 million sq. m.) of warehouse space. A second quarter 2009 report from Grubb & Ellis found that the average effective rental rate was down by 20 percent for U.S. logistics space.

Ocean shipping companies may face a new tax on the fuel oil their ships use. Other transport-related emissions also are under the microscope of governments and companies, as they prepare for a cap-and-trade globe. A shift is on between truck and rail, as customers heed the lower-emissions and efficiency/tonnage messages of railroads. And after a decades-long rise in freight miles traveled, fuel costs have companies reconsidering which trips are worth taking.

How will all of these factors affect logistics facility location? And could a return of manufacturing to the U.S. be driving a wholesale change in distribution patterns that results in a return to more and smaller distribution centers, decentralized from the fuel-guzzling location patterns of a decade ago?

A December report from the Lusk Center for Real Estate at the University of Southern California says an uptick in demand for that Inland Empire industrial space is imminent, and points to such markets as Ontario, Temecula and Chino as poised to benefit. The area’s comeback will be boosted by the $800-million federally backed expansion of I-215 in San Bernardino County.

The Lusk report also notes that the return of international trade to the area is not a one-way street: More exports are beginning to move through the ports.

Intermodals Dot the Map

Whether they’re moving goods in or out, intermodal and other freight transfer facilities will continue to rise in importance and on the skyline. Their locations range from the International Intermodal Center at the Port of Huntsville, Ala., to the expanding range of services at the Port of Brownsville in Texas to Union Pacific’s network of 24 such facilities.

This rising trend is giving rise to another: The dusting off of transport infrastructure assets in former capitals of freight movement, such as Boston Harbor, the railroad hub of Galesburg, Ill. (which just expanded its Foreign Trade Zone) and the Port of Cleveland, which is in the midst of a massive port movement and redevelopment plan launched by the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority.

In Joliet, Ill., CenterPoint Properties has just opened a new intermodal site to match their existing site in nearby Elwood, helped by the state’s new Intermodal Facilities Promotion Act.

The new site comes on the heels of opening a similar facility in the Houston-metro city of Beasley, near Kendleton, Texas, in July. That Texas facility has attracted, among other projects, a new finished vehicle distribution center from Kansas City Southern and Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics.

Under the Illinois legislation, state income taxes attributed to the jobs created at the facility will be placed in an Intermodal Facilities Promotion Fund. The Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity (DCEO) will administer the Fund to reimburse CenterPoint for infrastructure improvements. DCEO will award an annual grant of up to $3 million from fiscal years 2010 through 2016.

Illinois is currently among the top six exporting states in the country. The export-related nature of emerging logistics hub activity was reflected in an August 2009 project announcement by Menlo Worldwide Logistics, a subsidiary of Con-way Inc., which opened a new export logistics center in Joliet for Caterpillar. Con-way has the other side of Chicago covered too: One year ago it opened a new 110-dock-door next-day delivery service center in Rockford’s Rock 39 Industrial Park on I-39.

In Tennessee, BNSF is placing the finishing touches on a $200-million-plus expansion of its Memphis Intermodal Facility. When fully operational in 2010, the expanded 185-acre (75-hectare) facility will have doubled its capacity to 1 million lifts per year while reducing associated emissions.

CSX just opened a $6-million intermodal facility in Bessemer, Ala., that serves the needs of Mercedes-Benz, from a site that once hosted a manufacturing plant for Pullman railcars. Another has opened in North Baltimore, Ohio, just west of Toledo. The facilities are part of the railroad’s public-private, $842-million “National Gateway” plan for improving freight movement between the East Coast and the Midwest.

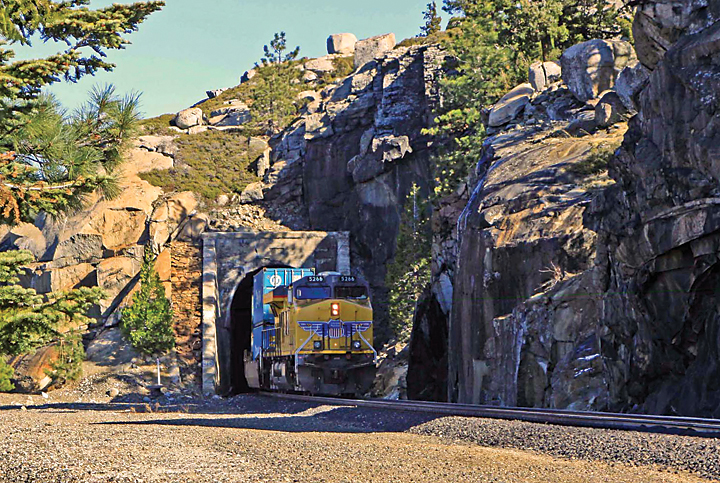

Similar efforts to streamline and open up their rail networks to more freight are being pursued by other Class I railroads, including Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific, which in November opened up its Donner Pass route to double-stack intermodal trains.

Double-stack intermodal container traffic now can move between Sacramento, Calif., and Reno, Nev. The Donner Pass route is the shortest rail route between Oakland and Chicago.

Other CSX National Gateway projects that will benefit local economies include expansion of the Charlotte intermodal terminal and the development of a terminal in Pittsburgh.

Porsche Assembles Much More Than Parts

On the other side of Pennsylvania sits the new multi-purpose, LEED-Gold certified Northeast Regional Support Center in Allentown from Porsche Cars North America, Inc. Developed by IDI, the 130,000-sq.-ft. (12,077-sq.-m.) facility has room to add another 25,000 sq. ft. (2,323 sq. m.). In addition to parts distribution, the center will host one of PCNA’s largest service training facilities, where the company will train at least 600 service technicians each year. Once an eastern sales office also moves in, the center will employ 32 full-time workers.

“The center is located right in the middle of one our most important sales regions and provides easy access to all major highways,” said Detlev von Platen, President and CEO, Porsche Cars North America, at the grand opening in October. “The time it takes to get parts to our dealers will be dramatically improved by use of a dedicated Porsche trucking system that will deliver parts to our dealers overnight and in some cases on the same day.”

The Allentown-Bethlehem-Easton, Pa.-N.J. CBSA has seen 14 new projects with a logistics component since January 2008, according to the Conway Data New Plant Database.

Rob Nemchik, general manager Porsche Logistics Service, LLC, said the new center in the Chrin Commerce Centre will serve 13 states, parts of Canada and 83 of Porsche’s 201 dealerships in the United States. The park is located near the site of a forthcoming highway interchange.

“Porsche will realize the positive synergies of combining three departments in one location, which is something we have already successfully established in our support center in Ontario, California, with a lot of success,” he said of a similar center established in 2005.

At a conference on transatlantic logistics hosted by the German-American Chamber of Commerce in Atlanta, and in a subsequent interview, Nemchik said the Boston-D.C. corridor had previously been served from PCNA’s other logistics facility in Atlanta. But business volume and fuel costs, combined with the service improvement potential, accelerated the drive toward a new facility, even after an expansion in Atlanta.

Working with Cushman & Wakefield, Nemchik’s team’s analysis pointed to two ellipses: “One was the I-81 corridor from Hagerstown to just north of Harrisburg,” he says. “The other was from Harrisburg in a northeasterly direction encompassing the Lehigh Valley. We visited 57 sites. It took us about nine months to a year. And the final selection was made 18 months prior to occupancy.”

Two project teams — one internal and one focused on the building — helped bring the project in seven weeks ahead of schedule and under budget. Nemchik credits the teams’ outstanding focus, as well as the fact that the slowing economy made available the best and brightest contractors.

Nemchik says his company neither looked for nor received incentives: “We wanted to make it a purely model-driven decision.” The final site was chosen after a previously chosen parcel in a neighboring township fell into a municipal dispute, he says.

Home Cooking

What’s not in dispute is the true synergy realized by locating different functions at one site. In the past, parts returned by dealers claiming a defect were evaluated by warehouse associates with varying degrees of technical competence, says Nemchik. “Now, if a part is sent back, 10 minutes later we have a highly qualified ASCE master certified technician inspecting the part, saying ‘Yes, it was manufactured incorrectly, and you need to go back to the supplier to be made whole.’ “

The German immigrant population of the area makes Porsche family members feel whole as they transit into town. Nemchick says several German executives have commented that the Lehigh Valley landscape reminds them of Germany: “It makes it feel more like home,” he says.

Nemchik thinks factors such as energy costs and the U.S. economic engine of small and medium-sized businesses could be conspiring to bring logistics, manufacturing and other sectors back into scalable range within “mega-regions.” The idea of the mega-region is that “everything that region could need to sustain a wide variety of industry is located there,” he says. Thus there could be a move under way from centralized hubs to more regional and smaller facilities.

For some regions and companies, says Nemchik, it may turn out that bricks and mortar are less expensive than long shipping routes.