| The site of Google’s new $600- million server farm in Lenoir will sit across Highway 18- 64 from a row of furniture factories representing the county’s traditional industrial base.

Photo by David Rodwell |

|

Google Arrival Boosts a

North Carolina County

ity vehicle tags in Lenoir, N.C., once promoted the small Foothills town as the “Furniture Center.” Those tags disappeared long ago, and the furniture industry, long the industrial cornerstone of Lenoir and Caldwell County, has been gradually shrinking over the last decade. The industry’s demise has accelerated in recent years, putting a decided dent in the area’s collective psyche. To be sure, there’s still a sizeable furniture presence in Caldwell, but the industry pales in comparison to its heyday.

The collective mood is changing as Google – a household word now, but a company that didn’t exist a decade ago – is building a US$600- million server farm directly across Highway 18- 64 from a row of furniture factories, some shuttered and some still producing the county’s best- known product. Google declines to discuss the square footage of the facility that will create up to 210 jobs over four years at an average salary of $48,000, or about $20,000 above the county’s average. That jobs promise can’t come soon enough for Caldwell County, which in December 2006 had an unemployment rate of 8.4 percent, the second highest among the state’s 100 counties.

That need for jobs is a major driving force behind state and local tax abatements and incentives offered to Google that some estimates now indicate could reach $260 million, although there seems to be some uncertainty as to exactly how much the company will receive. The numbers have prompted one prominent N.C. legislator to call for an examination of the state’s incentive process.

Convergence of Factors Led to Lenoir

Nestled in the Foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains about 70 miles (113 km.) northwest of Charlotte, Lenoir has a population of about 18,000. The electrical and water infrastructure installed for the furniture industry made it an attractive location for Google. The company chose Lenoir after considering other North Carolina sites and locations in New York and South Carolina. The process began in November 2005 when a consultant working for Google contacted the North Carolina Department of Commerce, and culminated with the official announcement of Lenoir as the choice 13 months and five days later.

Google’s global infrastructure team is charged with selecting data center sites. It is led by Lloyd Taylor, director of global operations, and Rhett Weiss, senior team leader of strategic development for Google’s global infrastructure, who guided the company’s search and negotiations with state and local officials. Weiss is a veteran site consultant and has operated his own consultancy, Dealtek.

Weiss, in an e- mail interview with Site Selection, says Lenoir was selected for the project due to a “convergence of location and site factors that we felt we could optimize for our operations.” He also cited the area’s work ethic, work force development resources, its community feel and scenic beauty as contributing factors.

Responding to a question on the influence of incentives on Google’s decision, Weiss referred to a figure of $100 million, a number that was initially estimated for the project.

“That entire hypothetical 30- year figure of $100 million consists of tax reductions that put North Carolina on par with other states,” Weiss says. “That is, those incentives come from reductions in property and sales taxes which don’t exist at all in many other states. Without these tax reductions to level the playing field, it would have been a better business decision for us to do our expansion elsewhere.”

Weiss cites Oregon, where Google has a similar data center in The Dalles, as an example. Oregon has no state tax. He also notes that Google doesn’t necessarily think North Carolina taxes are too high in general.

“It’s just that every state’s tax system has its quirks, and for our kind of investment- intensive business, North Carolina’s default tax situation wasn’t as favorable,” Weiss says. “We estimate we will still pay millions in tax revenue to the state and local communities, but it is our hope that in the decades to come our partnership with the community will benefit Lenoir, Caldwell County, and North Carolina as a whole much more than that.”

Google says details regarding its process for locating data centers are confidential. Secrecy shrouded Google’s search throughout the process, with the company using various pseudonyms such as Tapaha Dynamics. Google required local officials to sign 16- point nondisclosure documents. Documents released by the Department of Commerce indicate the project nearly collapsed last July following a North Carolina newspaper article on the project.

Lenoir Mayor David Barlow and Tim Sanders, a former Caldwell County Commissioner retained as a consultant for the county for the Google project, say landing Google already has done wonders for the psychological well being of county residents.

“We’ve needed some good news,” Sanders says, adding that the good feeling will grow considerably as the project progresses and the estimated 300 to 500 construction jobs are created.

John C. Howard, executive director of the Caldwell County Economic Development Commission, says the local effort employed the “power team” concept with a select group of local officials empowered to act as needed. Howard and Sanders give that strategy much of the credit in landing the Google project.

One of the challenges along the way was assembling the 41 parcels of land that comprise the 220- acre (89- hectare) site. That involved negotiating with about 20 homeowners, many of whom had lived there for decades. Another challenge was a rail line which runs through the property, and which Google insisted be closed for security reasons. Google paid the city and county $3 million in costs associated with closing the line, including establishing an offload facility for a rail customer.

Google Plans Local Hires

Google officials say they plan to hire the majority of the employees locally. They plan to work with Caldwell Community College & Technical Institute and Appalachian State University to develop training programs for positions including system administrators and technicians. They hope to see the server farm completed in the next year to 18 months. Site work has been under way since late last year for the single- story structure.

Google was a fledgling Internet search engine back in 2000, the year that may have seen Caldwell’s peak in furniture manufacturing with 9,500 employees. An accelerated spate of layoffs in subsequent years has seen that figure shrink to about 5,300. Caldwell officials have kept the state informed of the plight posed by the layoffs, says Jim Fain, secretary of the North Carolina Department of Commerce.

State and local officials believe the Google project has put Lenoir and Caldwell County on the economic development map. Howard says his office has fielded numerous calls from companies inquiring about supplying Google.

“The skilled work of local officials on this project demonstrates that they can do a great job of meeting the needs of potential investors,” Fain says. “Clearly, it has brought a lot of attention to the city and county.”

Meanwhile, Google’s search for additional data centers continues. The company is looking at numerous sites around the globe, including two locations in South Carolina – one near Goose Creek, outside of Charleston, and one in Blythewood, near Columbia.

| More

Regions

Get

WIRED

|

|

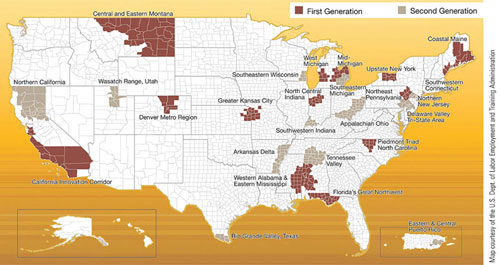

n January, the U.S. Department of Labor unveiled the second wave of grant recipients for its Workforce Innovation in Regional Economic Development (WIRED) initiative. Via the department’s Employment and Training Administration, 13 new regions will receive $65 million in funds to aid their efforts to transform their economies. The first group of 13 regions, named in February 2006, received a total of $195 million.

The second- generation WIRED regions are: Eastern & Central Puerto Rico; Southwestern Connecticut; Northern New Jersey; Delaware Valley Tri- State Area (Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware); Appalachian Ohio; Southeast Michigan; Northern Alabama and Southern Tennessee; Southwestern Indiana; Southeast Wisconsin; Arkansas Delta (Arkansas and Mississippi); Rio Grande Valley, Texas; Wasatch Range, Utah; and Northern California. Each of the newly named regions will receive an initial award of $500,000, with the ability to access a $4.5 million balance contingent upon completion of a regional implementation blueprint.

“This regional economic development strategy transcends political boundaries to better leverage a region’s assets to help workers succeed in the 21st century worldwide economy,” said U.S. Secretary of Labor Elaine L. Chao.

– Adam Bruns

|