![]()

hat’s what the U.S. Citizenship and Immigrations Services’ Immigrant Investor Pilot Program, known as EB-5, did for 779 foreign individuals and their 2,227 dependents in the most recently concluded fiscal year. All told, these investors poured some $428 million into U.S. projects projected to create more than 7,700 direct and indirect jobs. But the program has room for three times that many visas – which means the potential of up to $2 billion in investments.

At a time when foreign corporate money has its eyes on U.S. investment like never before, economic developers, immigration experts and international entrepreneurs yearning for U.S. citizenship are all climbing up the EB-5 learning curve. Even though the program is set to sunset in November 2008, there is little doubt it will be renewed, given renewal of interest in the program and resolution of some past legal difficulties involving legitimate investment oversight.

The level of interest is strongest in the Republic of Korea and China, where the People’s Bank of China is encouraging individual citizens as well as companies to invest abroad, in part to curb inflation. Korea, in turn, has relaxed its own rules regarding capital transfers out of the country. All of which means that all those trade missions to Asia might very well be focused on high-net-worth individuals as much as highly capitalized companies.

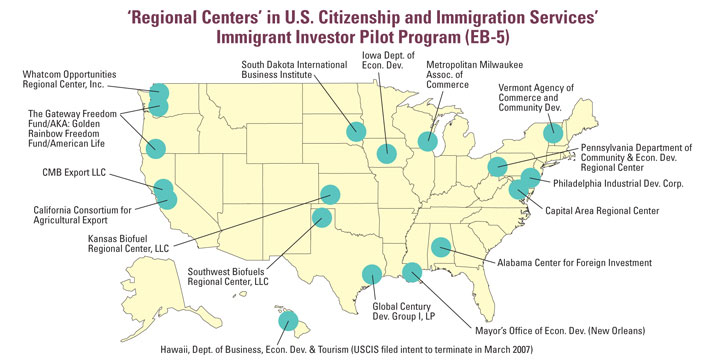

The EB-5 program works primarily via the establishment of “regional centers,” of which there are 17 across the country. Business sectors range from cargo warehouses in Washington to just about anything in New Orleans. Investments within these geographies that also fall within what are termed “targeted employment areas” (TEAs) need to be at least $500,000. Those outside the TEAs need to be at least $1 million and create 10 direct jobs. The regional center designation allows the additional variation of creating at least 10 direct or indirect jobs per investor. Projects run the gamut from hotels to heifer farms, with some falling into the industrial and manufacturing sector.

That’s the case with the regional center administered by CANAM and the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp., whose projects have included two facility expansions by Agusta Aerospace that have created 360 jobs. The most recent project by the company included a $15-million portion from the EB-5 program, which meant 30 individuals invested in that project.

Another recent regional center designation was granted in June 2007 to the Southwest Biofuels Regional Center, for a 49-county contiguous area in northwestern Texas and western Oklahoma, which is administered by a group of L.A.-based professionals who achieved a similar designation for a 21-county area in southwest Kansas. Also in June 2007, the entire state of Alabama, even with its recent business development success, was granted regional center status, through the Alabama Center for Foreign Investment.

One of the newest regional centers, Global Century Development Group I, is in downtown Houston, thanks in part to the legal counsel of Charles C. Foster, president and a founding member of Tindall & Foster law firm, who heads up its immigration law practice group. Foster also sits on the board of the Greater Houston Partnership, which has set as one of its stretch goals to increase foreign investment in the 10-county region to $225 billion by 2015.

“You could characterize it as a multi-use development project, with retail space, family space, hotel space and office space,” says Foster of the 60-block contiguous area in Houston’s Chinatown that also is in the city’s Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone #15. “The key there is it’s in the downtown business district, and helps stimulate other development in a part of the district that has been under-utilized.”

He says the application for another regional center is in the works, but the amount of time involved in the application and approval process – between 12 and 24 months – is a continuing sore point. So is the amount of recordkeeping required, which EB-5 expert Stephen W. Yale-Loehr of Cornell University has identified as falling into 17 different categories.

“It has to go through the central office in Washington, literally down to the desk of one person [Maurice Morrie Berez, Chief Adjudications Officer for the USCIS Foreign Trader, Investor & Regional Center Program] with multiple duties. They need a lot of economic data, and they hire their own accountant. But there is a big payoff, because it establishes a framework by which a foreign investor can invest. It’s very difficult for foreign investors to do it on their own. The regional center is not a guarantee, but it gives foreign investors a great deal of confidence.”

Foster says the under-utilization of the EB-5 program means the U.S. has not been nearly as competitive as Australia, Canada and other jurisdictions. He singles out Canada’s program for particular praise. It mirrors on the individual-investor level the sort of openness to immigrants that was demonstrated in 2007 at the corporate level by Microsoft’s development center location in Vancouver in order to legally attract foreign talent.

“Canada has a much more flexible program, which beats us hands down in ease,” says Foster of the immigrant investor program. “In 1997, with the takeover in Hong Kong, significant Hong Kong investment flowed in billions of dollars into Canada. We got almost none of that because of the complexity of our investment program and the length of time it took anything to get approved. We really weren’t in the game.”

“By the time we figured it out, the out-migration had already occurred,” adds Jeff Moseley, president and CEO of the Greater Houston Partnership. “That’s why you have nonstop flights to Hong Kong from Canada today.”

He hopes adjustments to immigration law will be helpful to Mexicans who, because of challenges to doing business in Mexico, already have been setting up satellite offices in Houston for many years. He refers to a Houston Chronicle account of the Mexican influx that described Houston development The Woodlands as “the prettiest city in Mexico” because of the number of Mexican expatriates who have settled there and brought their associates and families along.

“Mexicans since the earth has cooled have been looking to Houston for health care, banking, shopping and sporting events,” says Moseley. “We’re closer to Mexico culturally than we would be to Boston or San Francisco.”

That follows from a city whose former mayor, the late Louie Welch, used to say in the 1970s that Houston was an international city before it became a national city. It boasts 87 consulates and 23 headquarters of Fortune 500 multinationals. Twenty-two percent of Houstonians were born overseas and 15 percent are foreign nationals.

Some folks in Cleveland, Ohio, would like to be more international too. Attorney Richard Herman, of Richard T. Herman & Associates, LLC, is one of them.

“Mark Santo, president of the Cleveland Council on World Affairs, is leading a pilot initiative called the Talent Blueprint, which has been convened at the request of Akron-based Rob Briggs, CEO of Fund for Our Economic Future and vice chair of the Knight Foundation,” Herman writes in an e-mail. “The initiative is intended to bring together public and private entities to collaborate around the attraction of foreign talent and capital into Northeast Ohio [NEO]. We are in the early stages of fund development and planning for this initiative. One opportunity that we are pursuing is to educate the region on the merits of applying for a Regional Center license from the U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Service. The Regional Center is a key pillar of the NEO Immigration Blueprint.”

Leaders of the initiative expect to meet with Mr. Berez in the near future to discuss the regional center designation. In the meantime, Herman and his associates are circulating among a large group of national thought and policy leaders the idea of Cleveland and other Rust Belt cities creating “high-skill immigration zones” to welcome both foreign talent and capital back to communities once known for their large immigrant populations that have now seen that high rate of immigrant influx itself migrate to places such as Atlanta, Silicon Valley and Raleigh-Durham, N.C.

“There are fairly well identified skill shortages in the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Dayton corridor,” says Edward W. (Ned) Hill, Professor and Distinguished Scholar of Economic Development at the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs of Cleveland State University, when asked about the viability of such a program. “How do you target recruitment to respond to those shortages? Nothing stimulates mobility more than a job. Despite the ‘creative class’ nonsense, the creative class has to figure out at the end of the day where to pay for its tofu and burritos.

“Whether it’s India, China or Pennsylvania, the issue is talent and opportunity,” Hill says. “Nobody cares where it comes from.”

Site Selection Online – The magazine of Corporate Real Estate Strategy and Area Economic Development.

©2008 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.