"What’s so great about Norway?" some are asking in the wake of President Trump’s stated immigration preference.

A lot of things, it turns out. (Which might prompt some to wonder just how badly Norwegians would really want to emigrate.) And many of the nation’s positives come thanks to the fortunes of state-owned energy company Statoil, the second-largest gas exporter to Europe and the world’s largest offshore operator.

Arctic Now in December reported on the €5-billion (US$6.1-billion) investment by Statoil in an Arctic oil project called the Johan Castberg that will produce between 450 million and 650 million barrels of oil over 30 years. First oil from the project is scheduled for 2022, as the company’s oil and gas plays venture north — the Castberg project is at the 72nd parallel.

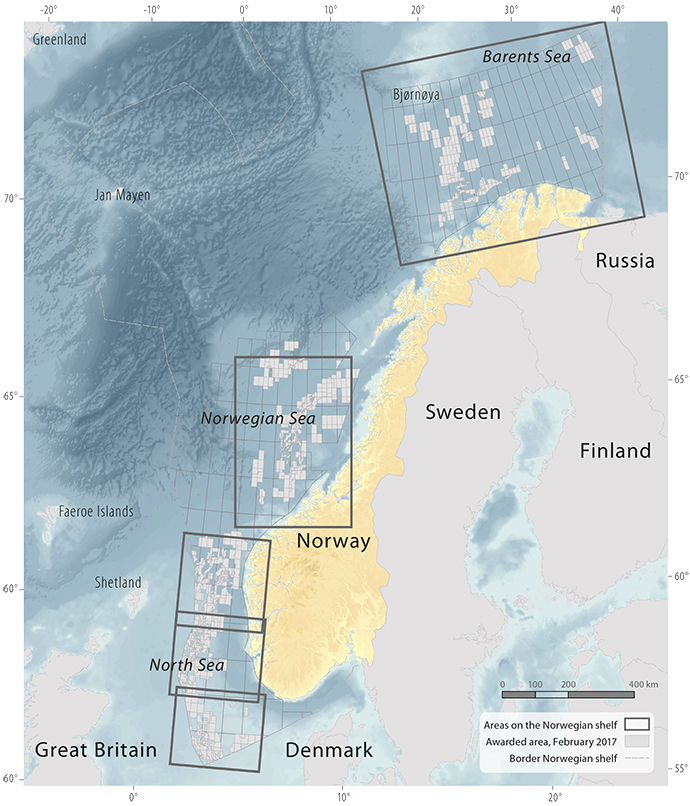

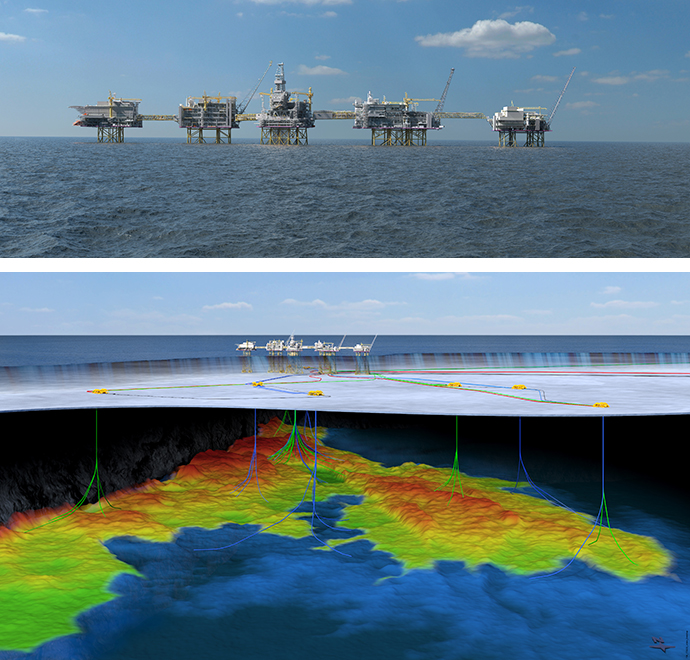

It’s one of over 40 Statoil assets spread across 30 fields on the Norwegian Continental Shelf, which includes the North Sea, Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea. Statoil is responsible for over 70 percent of all oil and gas production on the NCS, and since 2010 has increased its annual investments there by 75 percent.

Statoil’s projects play out in other directions too, with 20,000 employees in more than 30 countries. Its portfolio includes a 100,000-bpd oil field offshore Brazil; exploration and development in the Gulf of Mexico from shale and tight rock formations throughout the US. The company manages upstream activities from a base in Houston, and midstream, marketing and trading activities from Stamford, Connecticut, not far from where the company in October named a new wind farm offshore Long Island, New York, the Empire Wind project.

The 79,350-acre (7,372-hectare) site, secured by Statoil in a federal auction in December 2016, has the potential to generate up to 1 gigawatt (GW) of offshore wind power — enough to power about 1 million homes, or the equivalent of the number of homes that could be powered by the company’s European wind farms combined.

New York’s Clean Energy Standard mandates an increase in the share of renewables in its energy mix to 50 percent by 2030. As part of that effort, Governor Andrew Cuomo recently called for the development of up to 2.4 GW of offshore wind power by 2030.

"Statoil looks forward to working with all stakeholders as we move forward with the job of bringing offshore wind energy to New York," said Statoil’s Empire Wind Project Director Christer af Geijerstam. "We are committed to working with other developers, state officials, unions and the business community to develop a US supply chain for this and other offshore wind projects.”

Statoil currently has seven offshore wind projects online or under development in Europe, including the world’s first floating offshore wind project in Scotland — “a technology which could prove pivotal in generating offshore wind power for the U.S. west coast and Hawaii,” says the company. Statoil also recently announced its first solar investment in the 162-MW Apodi solar asset in Brazil, which will provide approximately 160,000 households with electricity. Another 385-MW wind farm, Arkona, is being constructed in the Baltic Sea by Statoil and Germany’s E.ON.

Underwater Factories

But the billions that have long provided the ballast for the Norwegian economy continue to come from the growing clusters of rigs proceeding from Norway’s coastline further and further into the Arctic, such as the Johan Castberg. The firm was called “The Norwegian Paradox” by The New York Times last year because of its vaunted clean energy push above-ground while the drilling for oil and gas continues underneath. And even as the nation’s $1-trillion investment fund considers a proposal to divest from petroleum companies, the oil and gas work continues.

“This is a great day! We have finally succeeded in realizing the Johan Castberg development,” said Margareth Øvrum, Statoil’s executive vice president for Technology, Projects and Drilling, in December when the company, along with Eni and Petoro, submitted a PDO (plan for development and operation). “Johan Castberg has brought challenges. The project was not commercially viable due to high capital expenditures of more than NOK 100 billion [US$12.7 billion] and a break-even oil price of more than US$80 per barrel. We have been working hard together with our suppliers and partners, changing the concept and finding new solutions in order to realize the development. Today we are delivering a solid PDO for a field with halved capital expenditures and which will be profitable at oil prices of less than US$35 per barrel.”

“Johan Castberg will be the sixth project to come on stream in Northern Norway,” added Arne Sigve Nylund, Statoil’s executive vice president for Development and Production Norway. “The field will be a backbone of the further development of the oil and gas industry in the North. Infrastructure will also be built in a new area on the Norwegian continental shelf. We know from experience that this will create new development opportunities.”

The Johan Castberg field will have a supply and helicopter base in Hammerfest and an operations organization in Harstad. Together with other operators of oil discoveries in the Barents Sea, Statoil is investigating the possibility of finding a profitable oil terminal solution at Veidnes.

Statoil has developed a strong specialist environment in Harstad based on 40 years of experience from operation in the north. Finnmark is another area the company will look to for workforce for the offshore component, which will require 90-100 professionals spread across three shifts.

“To ensure a long-term development of petroleum-related specialist jobs in Finnmark, Statoil will, in collaboration with other operating companies, suppliers and local authorities before the plan for development and operation is submitted to the authorities, look at possible initiatives to upgrade the general petroleum competence level in Hammerfest and Finnmark,” said Siri Espedal Kindem, senior vice president for the operations north cluster in Statoil, in December. “In the longer term this will lead to more local recruitment to the industry, and Finnmark may strengthen its position in the technology-driven development of the Barents Sea.”

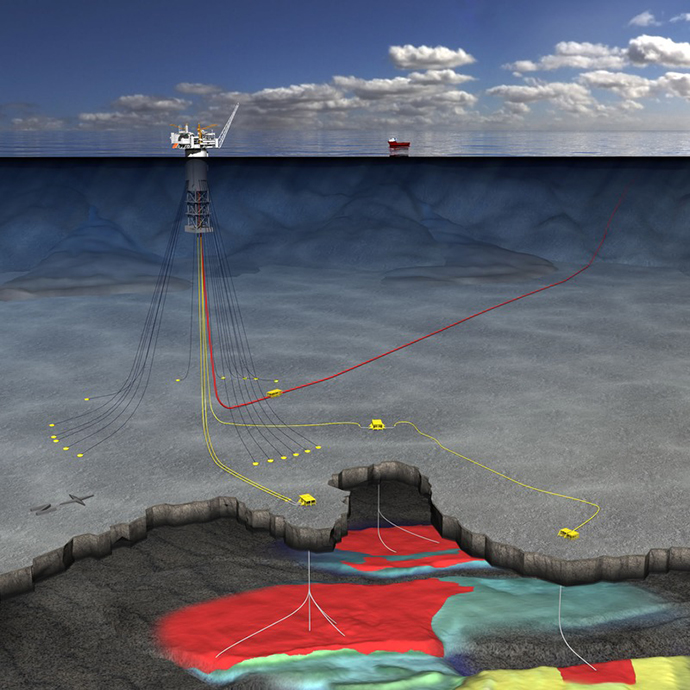

The costs of operating the field are estimated at some NOK 1.15 billion (US$146 billion) per year. “This will represent about 1,700 man-years nationwide, some 500 of which will be located in Northern Norway,” said the company, counting both direct and indirect employment effects. The subsea development includes 30 wells, 10 subsea templates and two satellite structures. Aker Solutions will do much of the work. “We are pleased to see that Norwegian suppliers again demonstrate their competitiveness and will play a key role in the development of Johan Castberg. The jobs generated nationwide during the development are estimated at almost 47,000 man-years,” Øvrum said.

The Undiscovered

According to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate and the Norway Ministry of Petroleum and Energy, the Norwegian continental shelf covers an area of 2,039,951 sq. km. (787,625 sq. miles), with oil exploration expanding from the North Sea to the Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea since 1980. "The North Sea is still the powerhouse of the Norwegian petroleum industry with 62 fields in production at the end of 2016," says the directorate. "In addition, there are 16 fields in production in the Norwegian Sea and two (Snøhvit and Goliat) in the Barents Sea."

The Norwegian part of the Barents Sea covers an area of 313,000 sq. km. (120,850 sq. miles), and is the largest sea area on the Norwegian continental shelf. The Barents Sea — home to only the Snøhvit and Goliat fields thus far — is also the sea area with the largest hydrocarbon potential. Only the area south of 74° 30’ N is open for petroleum activities.

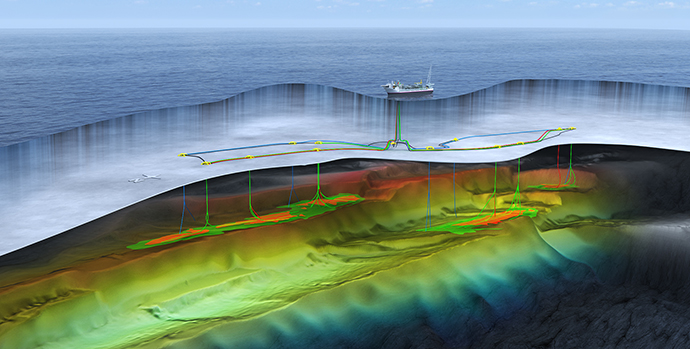

Currently, gas from Snøhvit is transported by pipeline to the Melkøya onshore facility, where it is processed and cooled down to produce liquefied natural gas (LNG), which is delivered to the markets on special LNG vessels, Statoil explains. “Produced oil and gas from Goliat are transported onto a Floating Production Storage & Offloading (FPSO), where the oil is processed, stabilized and stored for further export in tankers, while the gas is reinjected into the reservoir.”

“Most of the Barents Sea is considered to be a frontier petroleum province, even though there have been exploration activities here for more than 30 years, and the first discovery was made in the early 1980s,” says the company. “It is estimated that approximately half of the undiscovered resources on the Norwegian continental shelf are in the Barents Sea.”