Across the country, our cities, towns and suburbs — the local centers of commerce that form the backbone of America’s economy — are in a serious bind: They know they must have top-notch transportation networks to attract talent, compete on a global scale and preserve their quality of life. They know they need to get workers of all wage levels to their jobs. They also know they need to eliminate crippling bottlenecks in freight delivery. These communities are stretching themselves to raise their own funds and to innovate, but without a strong federal partner to address the twin demands of maintaining their existing infrastructure and preparing for the future are beyond their means. Recent trends, though, raise grave doubts about federal support for building and maintaining world-class infrastructure to support economic development.

Beth Osborne was deputy assistant secretary for policy, and then acting assistant secretary, at the US Department of Transportation from 2009 until March 2014, when she joined Transportation for America.

Before exploring those trends, it’s worth a moment to look at the role the federal transportation program has played. Most Americans know that their federal gas taxes have gone toward building the Interstate highway system. However, they may be unaware that most of their state highways and urban arterial roads and bridges have been built, maintained and replaced with 80 percent federal support, and that their transit networks, too, rely on those dollars for buying, repairing and replacing trains, tracks and buses.

“The 18.4-cents-per-gallon tax has remained flat since 1993 even as construction costs have risen by more than a third.”

Even when you include state and local contributions, federal funding accounts for just over half the money available to build and maintain our transportation system. In 22 states, federal funding accounts for 60 percent or more.

But here’s the scary part: The source of most of that money — the Highway Trust Fund — nearly became insolvent this summer, and is on life support heading into next year’s construction season.

Even as needs are rising, promised federal funding has stayed flat, while the revenue to fulfill that promise, which comes from federal fuels taxes, is dropping. Gas tax collections are sinking as fuel efficiency rises, and Americans actually are driving less each year on a per-capita basis. Not only that, but the 18.4-cents-per-gallon tax has remained flat since 1993 even as construction costs have risen by more than a third.

By mid-summer, the US Department of Transportation was warning states that they would have to slow reimbursements and cut payments by 28 percent if Congress did not find revenue to top up the trust fund by August. At the last minute, Congress used budget gimmicks such as “pension smoothing” to cobble together $10.9 billion to cover the trust fund shortfall until spring of 2015 — the start of the next construction season. Under this deal, we will have to collect money over 10 years in order to support 10 months of the transportation program.

Punch List or Punch in the Gut?

How does all this affect the world of corporate site selection? It could well mean that states and localities that thought they could deliver promised connections to make a particular site workable will find they have to cancel or delay such projects.

If things worked as they should, Congress would use the next several months to find agreement on a long-term funding solution — most likely a gas-tax increase — and update the expiring federal program to give communities greater ability to do innovative projects with strong return on investment.

If lawmakers fail to do so, it could cost the economy dearly. Today, nearly 65,000 of our bridges are deemed structurally deficient and, left in disrepair, could be restricted to truck traffic, or even closed. We have tens of billions of dollars worth of maintenance backlogs on highways, and even more on legacy transit systems — this as our population grows and continues to concentrate in metro areas with overburdened networks. After years of recession, local and state governments are nowhere near able to afford these bills alone.

Breaking New Ground, Reaching New Heights

The 3rd Bosphorous Bridge and Northern Marmara Highway Project, being built north of Istanbul by the IC İÇTAŞ — Astaldi Consortium ICA, in June was named Best Public-Private-Partnership Model of Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) Region in 2013 by EMEA Finance. The Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge is being financed by a nine-year, US$2.4 billion loan signed in August 2013 with the participation of seven banks. It is the largest project financing loan for a greenfield project in the Republic of Turkey’s history. The financing was completed this summer.

The new bridge joins the southernmost Bosphorous Bridge, which went into service in 1973, and the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge, completed in 1988, to serve a metro area of 17 million. It will be the first bridge in the world with an eight-lane highway and two-lane railway on the same level. When complete it will be the longest and widest suspension bridge in the world, and have the highest bridge tower in the world, at 320 meters (1,050 ft.).

— Adam Bruns

Photo courtesy of ICA

At the same time, with the right investment, the economic opportunity is huge, as I saw while serving at the US DOT from 2009 until earlier this year. During that stint I helped oversee the TIGER program, short for Transportation Investments Generating Economic Recovery, which was launched in the 2009 economic stimulus bill to help communities build high-impact projects that could not be funded out of our restrictive funding silos. The competitive grants are awarded based on bang for the buck and innovative thinking.

The response has been overwhelming, in the numbers and in the breadth and range of projects. There are way more deserving projects than funding.

In Chicago, the nation’s busiest rail hub, applicants from the public sector joined with freight rail companies to develop CREATE, a systematic effort to reduce bottlenecks that make it take as long for freight to cross the metro region as it does to get there from Los Angeles. Opening those bottlenecks will be a huge boon both for local commuters and for shippers nationwide.

In post-Katrina New Orleans, the Loyola Avenue Streetcar line extended transit service to the French Quarter, Superdome and downtown jobs and spawned nearly $3 billion in private sector development.

The first TIGER recipient — Normal, Ill. — used a grant to build a multimodal station that became the busy center of what had been a moribund downtown. Others rebuilt crumbling bridges that made better connections, including first-ever safe crossings for bicyclists and pedestrians; and still others improved access to ports and freight terminals.

Rendering courtesy of Foster + Partners

If It’s Not Too Dear

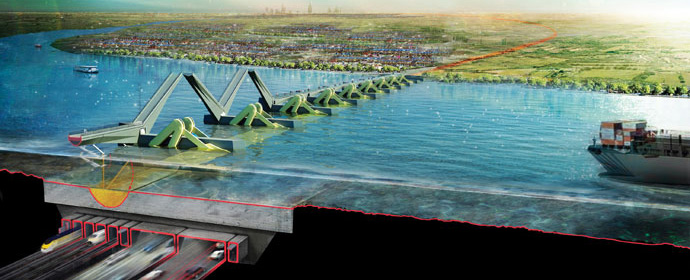

T

he grand plans for Foster + Partners’ proposed Thames Hub (pictured) on the Isle of Grain took a hit this year when the UK’s Independent Airports Council released a short list of proposals for airport hub expansion and the Thames inner estuary hub project was not there. The Thames Hub team — backed by London Mayor Boris Johnson and Andrew Lloyd Webber, among other luminaries — has responded with specific objections to the findings in the hopes of being added to the final short list, due to be released in September.

The Thames Hub team says its start-from-scratch option, which would remove the increased noise from aircraft approaches to Heathrow directly over London, is preferable to piecemeal expansion at Gatwick and Heathrow to help the UK keep global aviation hub pace with such places as Dubai and Istanbul. The Thames Hub project — which would take 15 years to build — includes four runways, multiple rail connections and a proposed initial capacity of 110 million passengers a year.

Among the obstacles to realization is the LNG import facility on Isle of Grain, especially as this energy resource figures prominently in the UK’s future energy mix. Another point of contention is the price tag. Foster + Partners projects Phase 1 airport and surface access costs at £26.3 billion (US$43.5 billion), while the Council’s independent assessment comes in at £68.9 billion (US$114.1 billion).

Webber, in a July commentary for The London Evening Standard, said Heathrow should never have been placed where it is in the first place, back in the 1930s, and said that airport “is past its sell-by date.” He also noted significant challenges with “concrete cancer” on the M4 highway that provides the primary airport access. By contrast, he wrote, the Isle of Grain site is “a flat piece of land right by the sea with very little, apart from the fact that you expect to see the occasional marsh ghoul, to recommend it visually. An airport there would create massive local job opportunities and justify major road and rail investment. It would revitalise the whole corridor between itself and London and, I believe, it would remap the economic geography of the capital for the better in the process, as well as relieving London of the noise and safety issues that are today ever present.”

A final decision from the Airports Council is expected in summer 2015.

— Adam Bruns

And while all of them required significant local, state and private-sector contributions, they also needed federal help to get off the ground. The resulting economic pay-off will result in more money flowing to household paychecks, business proceeds and ultimately to the treasury.

What we need from Congress in the coming months, then, is not only to return the transportation trust fund to stability, but also to remove unhelpful funding restrictions while expanding the use of competitive grants to reward innovative projects with multiple returns on investment.

In the 20th century our nation’s great task was to build an Interstate highway system to connect our states and metropolitan areas. Today, our challenge is to complete the transportation network within the cities, towns and suburbs that drive our economy. The risks to inaction are massive, but they are dwarfed by the opportunity we see with the right investment strategy.

In the Arena

Former US Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, currently co-chair of Building America’s Future, was in Atlanta in early August to testify at the state capitol on behalf of more investment in infrastructure. As Secretary of Transportation from 2009 to 2013, LaHood, a lifelong Republican, worked across party lines and frequently reminded partisans that “there is no such thing as a Democratic road or a Republican bridge.” He called the recent short-term extension (through May 2015) of MAP-21 by Congress “totally inadequate for any kind of planning, any kind of vision, for cities like Atlanta to make progress on big projects” that in turn generate economic development.

Building for America is recommending an increase in the gas tax of 10 cents a gallon, along with indexing the tax so it’s tied to the cost of living.

“If that had been done in 1993, when it was last raised, we probably wouldn’t be having this debate,” he said. “Raising the gas tax is absolutely critical to the future of Georgia, to do the things that you need to do to attract business and create jobs and do the economic development activities necessary to moving ahead. Infrastructure is critical, and having the money to build the infrastructure is as important as having a good plan.”

LaHood called the Georgia Ports Authority’s operation in Savannah “as good as any in the country,” and gave credit for its positive growth in part to active lobbying in Washington on its behalf by Gov. Nathan Deal and Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed. Though a T-SPLOST referendum in 2013 to support transportation improvements failed in most jurisdictions around the state, including Atlanta, he said the continued bipartisan cooperation between the two elected officials was still helping move projects forward in the state.

The Georgia Ports Authority’s rapid rise in activity over the past few years has come about in part because of bipartisan advocacy by Georgia Gov. Nathan Deal and Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, says former US Transportation Sec. Ray LaHood.

Photo courtesy of GPA

Former US Transportation Sec. Ray LaHood is co-chair of Building America’s Future.

Photo by Adam Bruns

But in recalling the $400 million in federal funds he helped obtain for job-creating highway improvements in his hometown of Peoria when he was an elected official and transportation committee member, LaHood said, “In order to get things done in transportation infrastructure, you have to have elected officials in the room when the bills are written. Georgia has no one. You have four congressional elections for four vacancies, and the electorate need to be asking the question, ‘Are any of you going to be in the room when Congress writes a transportation bill, looking out for Georgia’s interests?’ “

Big projects — such as major transit system improvements or high-speed rail — need big federal funding, he said, drawing attention to the economic corridors that are being created by light rail and streetcar projects such as the $100-million Atlanta Streetcar project expected to launch by the end of 2014. To date, since 2005 more than $25 million in federal funds also have been secured for the Atlanta BeltLine, a necklace of public parks, multi-use trails and transit that will re-use 22 miles of historic railroad corridors circling downtown and connect 45 neighborhoods. Other new transit investments are stoking economic momentum in Denver, Cincinnati and Washington, D.C.

LaHood cited Georgia’s recent success in attracting big facility locations from Caterpillar in Athens and State Farm in Atlanta. But he warned that the queue of corporate investors would dwindle in inverse proportion to growing traffic backups.

“These companies are not going to look at Georgia,” he said, “if you don’t have the infrastructure to accommodate the kind of facilities they want to build.”

— Adam Bruns