Industry reports and the experts make it clear: A new world order is in the making, with the United States essentially redrawing the world’s energy map.

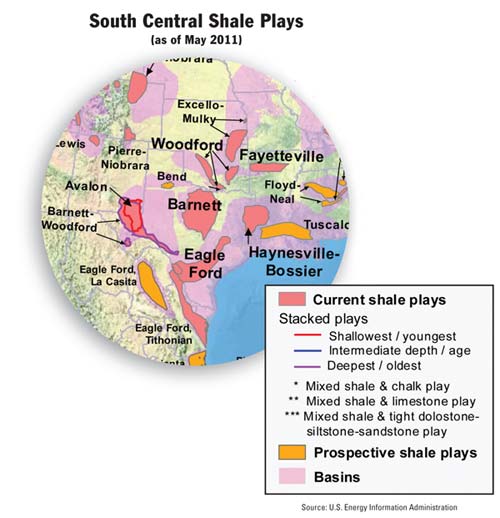

The shale oil boom has transformed lives and local economies throughout the country, but especially so in the South Central neighboring states of Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Arkansas. There energy companies and manufacturers catering to the oil and gas industry are investing tens of billions of dollars in drilling, pipelines, infrastructure, and new plants.

Major project announcements are almost a daily occurrence now in what can only be described as a revolution. And all of this capital investment is happening at a time when natural gas prices in the U.S. are trading at near historic low levels, which has a restrictive effect on drilling and exploration.

In Arkansas, the ancillary manufacturing was evident with Big River Steel LLC announcing plans on Jan. 29 to build a US$1.1-billion steel mill in Osceola that will directly employ 525 people with annual average compensation of $75,000 a year. A portion of the steel to be made will go toward the manufacture of pipe used in oil and gas production.

“I think it is the biggest announced project that we have ever had in Arkansas,” said Mike Maulden, director of external affairs for Entergy, the electric utility that will be supplying power to the future plant in Mississippi County, about 50 miles (80 km.) north of Memphis.

Meanwhile, the economic impact of the Fayetteville Shale play in a nine-county area of north-central Arkansas in 2012 alone totaled $4 billion with more than 16,000 jobs, according to a study by the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas.

“To put this in perspective, from 2001 to 2010, the state of Arkansas experienced only tepid growth in employment. Without the employment associated with the exploration and development of the Fayetteville Shale, Arkansas would have suffered a ‘lost decade’ where employment at the end of the period was lower than employment at the beginning,” said Kathy Deck, director of the research center.

Saint-Gobain Corp. said in August that it would build a new $100-million plant in Saline County, Ark., to manufacture ceramic spherical beads designed to be inserted into underground fractures in oil and gas wells to “prop” open fractures and increase productivity of the wells. The French company already operates two plants in Arkansas — one in Fort Smith and another also in Saline County. The new plant to come online is still under construction, with commercial production expected later this year, says company spokesman Bill Seiberlich.

Huge multi-billion-dollar capital investment announcements have become almost the norm of late in Louisiana, all due to increased activity in oil and gas. Magnolia LNG announced plans on Jan. 17 to develop a $2.2-billion natural gas liquefaction production and export facility at The Port of Lake Charles. Just two days before, G2X Energy Inc. said it would build a $1.3-billion natural gas-to-gasoline facility at the same port in Southwest Louisiana. Sasol, a chemical and synthetic fuels company based in South Africa, plans to spend up to $16 billion and $21 billion to build the first gas-to-liquids plant in the United States, in Westlake in Calcasieu Parish.

Cheniere Energy has the only permitted LNG export terminal in the continental U.S. now under construction at its Sabine Pass LNG facility in Cameron Parish. Company officials say construction of two liquefaction plants of a total of four planned near the Texas-Louisiana border on the Gulf of Mexico is ahead of schedule. The $6-billion project is expected to create 3,000 construction jobs.

German steelmaker Benteler will build a $900-million plant to produce seamless pipe dedicated for oil and gas field use. The project will be built on 330 acres (134 hectares) at The Port of Caddo-Bossier in the northwest part of the state.

In all, more than $60 billion in manufacturing investments related to oil and gas are planned over the next four years, according to a recent study by Louisiana State University.

Bigger Than Nuclear

Cheniere Energy’s liquefaction plant and export terminal in Cameron Parish, La., is the only permitted LNG export terminal in the continental United States.

Image courtesy of Cheniere

Texas oil production has nearly doubled in the last two years. The latest data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows production averaged 2.14 million barrels a day in November — an increase of 900,000 barrels a day from November 2010, worth about $32 billion a year.

In the prolific Barnett Shale play in North Texas, possibly the most active natural gas reserve field in the U.S., more than 18,000 wells are in production. The Barnett has created more than 100,000 jobs with an economic impact of more than $65 billion from 2001 to 2011, according to a 2011 study by the Perryman Group.

“I think it is the biggest announced project that we ever had in Arkansas.“

— Mike Maulden, director of external affairs, Entergy, on Big River Steel’s planned $1.1-billion steel mill

But it is the relatively new Eagle Ford Shale play in South Texas that is fueling a renaissance in Texas and garnering much of the excitement. It is believed to be one of the most significant oil and gas discoveries in the country. About 38,000 jobs have been created, with “man camps” popping up throughout a 14-county region in response to the boom.

Oklahoma’s economy is flourishing, where more than 340,000 jobs are directly or indirectly fueled by the oil and natural gas industry. The Department of Commerce reports that 126 company projects were announced in 2012 with about half of them manufacturers. The fourth-highest job growth rate belongs to Oklahoma with more than 62,400 new jobs created in two years. The state’s unemployment rate stands at 5.7 percent, one of the lowest in the nation.

Gov. Mary Fallin has called for more conversion from state gasoline-powered vehicles to compressed natural gas vehicles. The governor says using CNG cars and trucks will save taxpayers millions of dollars in fuel costs, while supporting energy jobs in the state.

Drilling activity in Oklahoma has increased as producers are concentrating more of their efforts on oil rather than natural gas due to pricing. Continental Resources Inc. will ramp up activity in the South Central Oklahoma Oil Province, or SCOOP, as the company calls it. SandRidge Energy Inc. appears to be staking its future on the emerging Mississippi Lime play in northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas, according to published reports.

Greg Dewey, SandRidge’s vice president of communications and community relations, said the company plans to drill 570 horizontal wells in the Mississippi Lime in 2013.

“We project generating over a billion dollars of economic activity in [northern Oklahoma] alone.“

— Greg Dewey, vice president of communications and community relations, SandRidge

“At $3 million a well, we project generating over a billion dollars of economic activity in that area of our state alone,” Dewey told the Oklahoman. Companies working in Oklahoma produced more than 75 million barrels of oil last year, according to the Oklahoma Tax Commission, which collects gross production taxes.

David Dismukes, associate director and a professor at the Center for Energy Studies, Louisiana State University

It bears repeating: This boom in the South Central states is happening at a time when natural gas prices are depressed, trading in the U.S. below $4 per million British thermal units. Industry experts say the lower prices have not been conducive to “upstream” investments — exploration and drilling — which have slowed.

But “downstream” projects — the building of infrastructure to move and convert the gas to different types of products — continues unabated, and U.S.-based manufacturers will enjoy a decided competitive advantage with lower energy costs.

Much of the gas now entering the marketplace in abundance was essentially drilled for when prices were higher, says David Dismukes, associate director and a professor at the Center for Energy Studies, Louisiana State University.

“The blowback is from all that activity from when gas was eight, nine or 10 dollars per million BTUs, and it is still going on,” he says. “So all those wells that were drilled to date are still producing and they are still putting gas to the market. The drilling has now slowed down. But the market cost of just continuing a well to produce after you have completed that well is not very high, certainly lower than even the low market gas prices that we have now.

“When prices rise, you will see more investment on the upstream side of the business,” he says. “Right now the new announcements are on the downstream side of the business in terms of the users. What you will find is that you will have those users and suppliers and producers blowing and going when prices increase.”

In other words, America’s shale revolution will likely only get bigger. Fatish Birol, chief economist for the International Energy Agency, said in the World Energy Outlook 2012 that the surge in U.S. oil and gas production is “the biggest change in the energy world since World War II.” Birol told the Reuters news service, “This is bigger even than the development of nuclear energy.”

Cycle-Proof?

All four South Central states (and others as well) are benefiting as the result of two technologies — horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing — coming together. These technologies, which have been used for decades, (the first true horizontal well was drilled in 1929 although it was not economical to drill horizontal wells until the 1980s) have enabled energy firms to go straight to the source rock, which is shale.

Before horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing, drillers had to explore for isolated pockets of hydrocarbons that had leaked out of the shale into surrounding sands. Those pockets were getting harder to find and natural production in the U.S. had been declining for decades.

But Mitchell Energy changed everything with its pioneering production efforts in the 1980s, perfected in the 1990s, of combining horizontal drilling with hydraulic fracturing in the Barnett Shale in North Texas. The Barnett remains the nation’s largest producing natural gas field, producing 7 percent of the total natural gas used in the U.S.

Texas continues to lead the nation in oil and gas production, with most of the larger capital project announcements of late in support of delivering product to market. Howard Midstream Energy Partners announced on Feb. 6 that it will begin building in April a cryogenic natural gas plant that will process 200 million cubic feet of gas per day. The plant will clean raw natural gas by separating impurities to produce pipeline quality gas.

Howard is also in the process of constructing an import and export logistics railroad hub for oilfield-related services and products, including condensate and natural gas liquids. Both facilities will serve producers and midstream customers operating in the Eagle Ford with a total cost of about $100 million.

Something to Show For It

The economic impact in the 14-county area of the Eagle Ford Shale remains staggering, with more than $19.2 billion in output; $10.5 billion in gross regional product; $211 million in local government revenues; $312 million in state revenues and 38,000 full-time jobs in 2011, according to a study by the Center for Community and Business Research at The University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) Institute for Economic Development.

Getting a handle on the explosive growth has been a challenge for many South Texas communities. UTSA is working with them to essentially cope and create sustainable growth for the long-term. Eagle Ford is expected to bring 117,000 workers to the area between now and 2021 and have a $90-billion economic impact on the region.

“Our goal is to integrate business, community and work-force development services under one roof to create the synergy for sustainable development for the region,” says Gil Gonzalez, who heads the Small Business Development Center at UTSA. “We are working with municipalities to give them the tools so that they can manage the growth that they are experiencing right now. We want to help them develop a plan to invest in the future and not go through a boom/bust cycle that leaves you with little to show for it afterward.”