They’re cities of dreams. They’re the nation’s glamor capitals. But they’re attracting the lion’s share of Opportunity Zone funds meant to spark the economies of neighborhoods struck more by poverty than by fame.

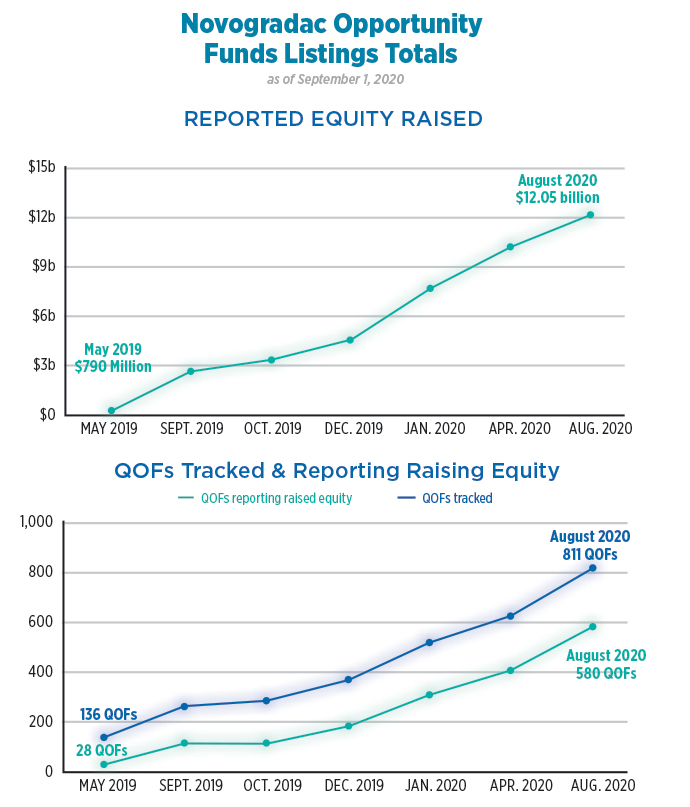

Analysis published in September 2020 by tax break experts Novogradac found that investment in more than 800 Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) tracked by the organization exceeded $12 billion, though the total amount in all QOFs was “undoubtedly more.” The White House Council of Economic Advisers put the total around $75 billion. But where are those funds targeted for action?

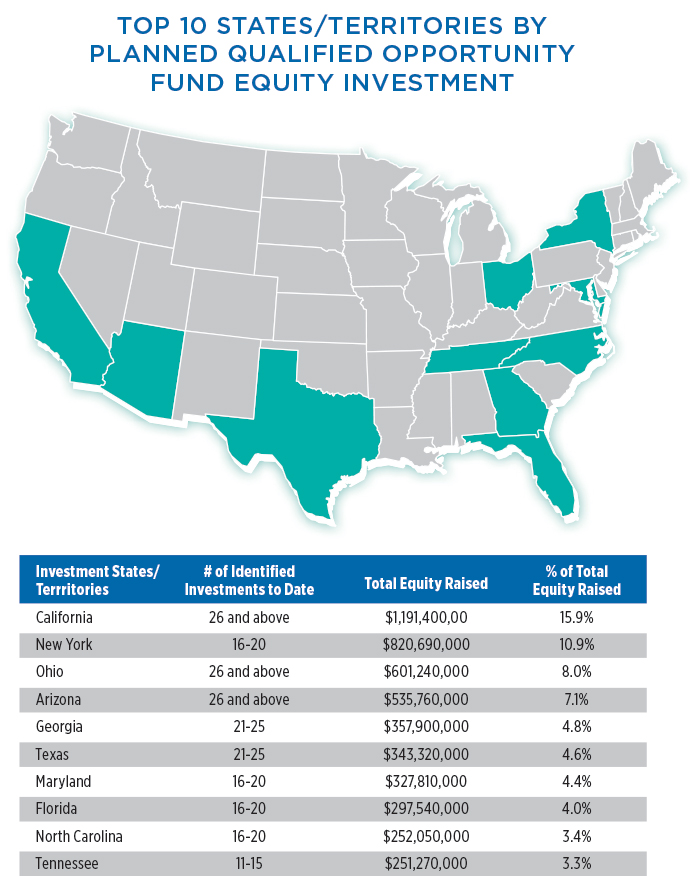

“QOFs can focus on a national, regional, state or city investment areas,” wrote Michael Novogradac, noting a pretty even split among those with a national, multi-city or single-city focus. Based on available information, California and New York are the leading states for QOF investment, driven by their star-struck cities.

“Based on Novogradac’s numbers, New York City-focused QOFs have raised $696 million and Los Angeles-focused QOFs have raised $509 million — much of which is attributable to the number of low-income areas in those metro areas,” the firm reported. “The investment amounts in New York City and Los Angeles combine to make up 10% of the national investment total.”

Could OZs help the nation recover from the pandemic? Both presidential candidates thought so.

“As the nation looks for tools to help spark a recovery from the COVID-19-caused economic recession, the OZ incentive provides a unique tool to fund development in low-income communities,” wrote Novogradac. “The continuing increase in equity investment provides reason to see the OZ incentive as another key tool in the fight to rebuild America’s post-pandemic economy.”

Magical Thinking vs. ‘Magical Capital Stack’

Look around and ask around, however, and you may encounter a dimmer view. It turns on definitions: “Equity” in the fiscal sense vs. “equity” in the social justice sense, and “underserved” as in neighborhoods lacking basic amenities and services vs. “underserved” markets waiting to be more thoroughly pounced on for profit.

“The projects in Opportunity Zones that I and others might hope to see need incentives far beyond what the Opportunity Zone provides.”

“The reality is it has not provided much opportunity,” says Mary Ellen Wiederwohl, chief of Louisville Forward, of the OZ program. “Louisville was the first city in the country to have an Opportunity Zone prospectus. We worked with Bruce Katz to put together a pitch deck, and got way out there promoting that. We don’t have a glaring large success. There are smaller examples, but projects I’ve seen around the country are ones that were already priced to move. The projects in Opportunity Zones that I and others might hope to see need incentives far beyond what the Opportunity Zone provides.

“The real incentive,” she continues, “goes to the investor who gets the capital gains tax break. That’s great if it makes them look at opportunities they might not consider otherwise. But these projects need subsidy in addition to investment. They often need 10% to 20% subsidy via tax incentives, direct government investment or tax credits. Unless you have the magical capital stack that lines up neatly with all of those things, it’s been hard for an OZ project to work, because most of those funds want a market rate return, and these are not in market rate areas.”

The reason they’re not market rate areas goes to a deeper discussion on racial justice (where Louisville has been in the spotlight — see p. 164). “Going forward, there will be and should be additional scrutiny on how incentives are awarded,” Wiederwohl says. “A couple years ago, we changed our decision matrix, which now includes a higher wage requirement, and we have offered additional incentives for companies that will locate in a CDBG-eligible area and hire more than 51% of staff from within the area. Even so, it’s very difficult to attract investment to historically disinvested areas. Real estate bias, discrimination and even outright racism … the whole ugly history in this country of redlining and urban renewal… we had the chance to get the laws right, but we didn’t get the fiscal side of the house right as a country. We rearranged financial resources, many can’t get ahead, and unfortunately many of them are black and brown.”

Real Projects

I keep asking experts where the projects are that showcase the best intentions of the OZ program. Where and in what form are QOF funds actually being spent on real projects we can see and touch, especially those involving anchor employers in growth mode? Answers are sparse. And that’s because the projects themselves are sparse. But they’re there.

Economic Innovation Group is a D.C.-based organization that convenes leading experts from the public and private sectors, develops original research, and advances “creative policy proposals that bring new jobs, investment, and economic dynamism to U.S. communities.” As part of its advancing of geographic inequality into the conversation, it has kept track of OZ activity with a series of maps.

The “All Activities” map looks robust at first glance (see all the EIG OZ resources at eig.org/oz-activity-map). There are dozens and dozens of mixed-use, hospitality and residential projects looking to locate in the generously defined zones and make some money with higher-dollar customers, with the possible byproduct of some ancillary low-level job creation. As more than one OZ residential announcement crossing my desk has proclaimed, the projects will offer “luxury” market-rate living, and the locals benefit from the privilege of helping build them. But even as they get paid for that work, it eventually ends, and the projects can then have a displacement effect commonly referred to by the catch-all term “gentrification.”

By the time you sort down to the “Operating Business” level, however, you have 32 projects nationwide. That’s barely a drop in the bucket when considering the more than 800 QOFs Novogradac is tracking, or the 8,760 designated OZs in all 50 states, D.C and five U.S. territories.

But they are operating businesses nonetheless, serving as OZ anchors. And as such, they provide glimpses of American ingenuity, determination and civic responsibility at work. A few highlights from among the 32 projects, as documented by EIG:

In City Farms intends to build a 180,000-sq.-ft. aquaponics facility to farm both fish and vegetables on an old industrial site encompassing 25 riverfront acres in Duquesne, Pennsylvania. Backed by the social impact investors Hollymead Capital, the nonprofit Food 21, and an OZ fund, the $30 million facility is expected to initially employ 130 local workers, potentially expanding to 275.

LignaTerra Global, a North Carolina company that makes a composite wood material used in green construction plans to invest $31 million into opening a new 300,000-sq.-ft. factory that will employ about 100 people on an old paper mill site in Lincoln, Maine, that is located in an Opportunity Zone.

Funds from Blueprint Local, an opportunity fund, will make it possible for developers Penn Station Partners and Beatty Development Group to convert the historic Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore into a modern facility with new retail, restaurants and office space by 2022. The investment comes alongside $90 million in improvements from Amtrak and $3 million in state historic tax credits.

In coordination with the non-profit Central Baltimore Partnership, Blueprint plans to form a workforce development program and community benefits district. The investment is the first phase in a major planned transformation of the rail station into the anchor of a vibrant mixed-use area in a struggling corner of the city.

Vicksburg Forest Products LLC used Opportunity Funds to invest in the Anderson-Tully Mill in Vicksburg, Mississippi, saving 125 jobs.

CORI Innovation Fund (CIF) invested in Sho.AI Inc. (Sho), a provider of AI-enabled software solutions for brand creation and management. CIF is a Qualified Opportunity Fund that invests in high-growth technology companies supporting job creation and revenue generation in small towns across America. Sho is based in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, a community that is part of the Center on Rural Innovation’s Rural Innovation Initiative. Sho is expanding to new offices in an area of Cape Girardeau designated as an OZ.

Erie Insurance Co.’s Opportunity Fund invested in Whitethorn Digital, a small independent gaming company located in Erie, Pennsylvania. The investment will allow the company to purchase and refurbish an office building in downtown Erie and scale up their staff from eight to 20-plus employees in the coming years.

“The continuing increase in equity investment provides reason to see the OZ incentive as another key tool in the fight to rebuild America’s post-pandemic economy.”

Bitterroot Gateway Development has acquired a vacant five-building complex inherited by the county to create a home for Montana Studios, a media production venture, in downtown Butte, Montana. The building will be used for production sound stages, interior filming, offices, educational and training rooms, set locations and apartments and condos for those working on movie, TV and other film projects.

The project will use some bank financing in addition to OZ capital, new-market tax credits, and possible historic tax credits. Developers expect it to cost $10-12 million.

CoLabs in Tampa was one of the first known startups to complete an Opportunity Zone equity capital raise. It develops software-as-a-service applications using AI and machine-learning, has raised $6.2 million as a Qualified Opportunity Zone Business, employs 22 people and plans to boost that headcount by 50%.

With an equity infusion from the Flexible Capital Fund, early-stage vertical farming startup Ceres Greens will build its first production facility inside an Opportunity Zone in Barre, Vermont.

The non-profit Fredericksburg Food Co-op is establishing an Opportunity Fund to complete a $1.5 million capital raise to build a new grocery store in northern Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Colorado Outdoors Pearl Fund, LP invested $1 million from its QOF into outdoor industry holding company Wedge Brands, LLC. Wedge then announced plans to build a 76,00-sq.-ft. distribution and third-party-logistics center on the Colorado Outdoor campus in Montrose, Colorado. Wedge Brands will be investing an estimated $14 million in the new facility.

New Orleans–based Launch Pad has established itself as a qualifying OZ business in order to finance the expansion of its incubator and co-working space model into OZs across the country.

In New Mexico, supported by Verte OZ, NAVF Carbon will work to reverse carbon emissions by generating carbon offsets through the management of tribal forests. The carbon credits are sold to companies to offset their carbon footprint in compliance with California carbon emissions regulations. By implementing carbon sequestration projects on Native American lands, NAVF aims to deliver carbon credits that will yield profit while aligning with Native American cultural and environmental values.

SHINE Medical Technologies, a growing Wisconsin-based medical isotope company, will move to an Opportunity Zone in downtown Janesville.

10X Engineered Materials’ Opportunity Zone investment is helping to turn a once-blighted area in Wabash into a viable hub of activity rooted in sustainable practices. The company plans to take in byproduct from the installation industry that would otherwise go in a landfill and convert it into various products, primarily an abrasive that can be used in water jet cutting and abrasive blasting.

Once complete, 10X is expected to divert about 36,000 cubic yards of waste produced by area manufacturers away from the landfill and plans to employ 26 full-time employees.

What Can Big Business Learn From Small Businesses’ Experience?

In late October, Smart Growth America (SGA), in partnership with Citi and the U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives’ Democracy at Work Institute, published “Unrealized Gains: Opportunity Zones and Small Businesses,” with a particular focus on the minority-owned and legacy businesses that form the social fabric of many neighborhoods in these areas. (For the complete report, visit smartgrowthamerica.org.)

“Small businesses help build sustainable competitive advantages and enduring enterprises. This gives people jobs and, perhaps most importantly, it creates long-term wealth,” SGA said. “But there are serious challenges for legacy and small businesses — especially those that are minority-owned — due to limited access to capital, lack of investment in community infrastructure, the continued challenges of a globalizing economy, and now an unforeseen pandemic fueling a new economic crisis. So it is vital to determine if this new incentive is helping to close economic gaps — or widen them further.”

The authors examined Opportunity Zone activity and investment trends across 93 OZs in four metro areas: Miami, Florida; Atlanta, Georgia; Louisville, Kentucky; and Washington, D.C.

Census tracts that have been designated as Opportunity Zones generally consist of disinvested areas that have higher rates of poverty when compared to their encompassing cities, the report explained. “The starkest economic disparities are captured through the employment status of individuals living within Opportunity Zones compared to the general population. Residents of Louisville’s Opportunity Zones are experiencing an unemployment rate over three times higher than the city on average, with over 10% of the workforce without a job in 12 of the 19 Opportunity Zones.”

The majority of housing units located within the examined OZs are occupied by renters, the report found. “Louisville shows the sharpest contrast in housing tenure as a mere 23.1% of housing units across the city’s 19 Opportunity Zones are owner-occupied compared to 60% in the Louisville-Jefferson County Metro Government area.”

The report cited SEC data for OZ funds’ overall target sectors. In total, 46% of Opportunity Zone funds reported to be investing in real estate, while 45% reported to be operating as pooled investment funds and therefore have investments across different sectors. The remaining 9% includes healthcare, technology, construction and investments.

The report cited the useful portal The Opportunity Exchange, which has over 400 Opportunity Zone projects and businesses listed, and The National Opportunity Zones Marketplace OppSites with 1,030 projects and businesses listed. Their findings in general:

- The design of the tax incentive makes it difficult for existing businesses to qualify for and secure investment. Equity investments, the tangible asset requirement, and the 10-year investment timeline have driven a majority of Opportunity Zone Funds and investments towards real estate. “This has pushed business investments — especially existing small businesses, which the tax incentive is expressly intended to support — to the periphery,” the report says. “One barrier to small business investment is that the tax incentive does not allow Opportunity Zone investors to invest Opportunity Zone capital in the form of debt. Debt is the primary source of capital for small business growth, but the tax incentive is structured to favor longer term equity investments with higher return requirements than can typically be offered by low-growth small businesses.”

- There’s often a mismatch between the investment targets of Opportunity Funds and the investment opportunities and needs of minority-owned and legacy businesses.

- There’s a spatial mismatch between who is investing in Opportunity Funds and who is most affected.

- A lack of impact or reporting guidelines has encouraged investors to seek out stable, high-rate-of-return investment opportunities such as commercial real estate “that may or may not bring the social impacts desired by the community or legislators.”

The report makes the following recommendations:

- Create a new class of investment priorities to elevate investments in existing businesses, including allowance of investments made in the form of debt; allowance of investments in vehicles focused on employee buyouts (ESOPs); changing the 70/30 tangible asset requirement for some existing businesses; streamlining legacy and minority-owned business designations; and offering a guarantee of the tax benefit to those investing in existing small businesses within OZs.

- Give residents the opportunity to be investors by “waiving the requirement that investments be made only through unrealized capital gains, which only a small slice of Americans even possess.”

- Require investments to reinforce local plans by tightening the legislation to require OZ designations to be based on existing community planning efforts and frameworks.

- State and local governments should be active in guiding investments.

- Prepare businesses for potential investment with technical assistance or, for example, by creating “an academy or incubator program for minority-owned businesses within Opportunity Zones in high-growth industries.”

- Improve transparency and accountability to track the impact of Opportunity Zone investments.

- Center community benefit, i.e. prioritize positive community impact, guided by the community itself.