Aerospace companies are key beneficiaries of the federal government’s transition from the NASA-run Space Shuttle program to the next generation in space travel. The Shuttle program has just a handful of missions left (see the Florida spotlight, page 244), but private-sector initiatives are on track to pick up the baton. Astronauts and cargo must still be sent to and from the International Space Station, and other out-of-this-world destinations in due course, so funds are being allocated to aerospace companies to develop the necessary transportation platforms.

In August 2009, NASA announced that its Commercial Crew and Cargo Program would apply Recovery Act funds to efforts in the private sector to develop and demonstrate human spaceflight capabilities. According to NASA, “These efforts are intended to foster entrepreneurial activity leading to job growth in engineering, analysis, design and research, and to economic growth as capabilities for new markets are created. By developing commercial crew service providers, NASA may be able to reduce the gap in U.S. human spaceflight capability.”

In other words, NASA plans to outsource human spaceflight.

Commercial Spaceflight Takes a Giant Step Forward

NASA is using its Space Act authority to invest up to US$50 million dollars in multiple competitively awarded, funded agreements through a program known as Commercial Crew Development, or CCDev, which awards Space Act Agreements (SAAs) to winning private-sector bidders. Several were announced in early February.

NASA has awarded Space Act Agreements to Blue Origin of Kent, Wash. ($3.7 million); The Boeing Co. of Houston ($18 million); Paragon Space Development Corp. of Tucson, Ariz. ($1.4 million); Sierra Nevada Corp. of Louisville, Colo. ($20 million); and United Launch Alliance of Centennial, Colo. ($6.7 million). The agreements are for the development of crew concepts and technology demonstrations and investigations for future commercial support of human spaceflight.

“These selections represent a critical step to enable future commercial human spaceflight,” said Doug Cooke, associate administrator for Exploration Systems at NASA. “These impressive proposals will advance NASA significantly along the path to using commercial services to ferry astronauts to and from low Earth orbit, and we look forward to working with the selected teams.”

“The commercial crew initiative will create thousands of new high-tech jobs, help open the space frontier with lower-cost launches and inspire a new generation with high-profile missions,” said Bretton Alexander, president of the Washington, D.C.-based Commercial Spaceflight Federation (CSF), which promotes the development of commercial human spaceflight, pursues ever higher levels of safety and shares best practices and expertise throughout the industry. CSF member organizations include commercial spaceflight developers, operators and spaceports. “This initiative is on par with the government Airmail Act that spurred the growth of early aviation and led to today’s passenger airline industry, which generates billions of dollars annually for the American economy.”

Adds Alexander, “Investing in commercial spaceflight will allow us to create U.S. jobs, rather than continuing to send billions of dollars to Russia to fly our astronauts to space. With so many capable American companies here at home, why would we send all of U.S. human spaceflight to Russia? Let’s create those thousands of jobs right here in the United States.”

CCDev will reduce the gap in U.S. human spaceflight by using launch vehicles that are either already flying today or are close to launch, such as the Atlas, Taurus and Falcon, explains Alexander. “Upcoming cargo flights mean that the Atlas, Taurus and Falcon rockets will have long track records by the time astronauts are placed onboard. Safety is paramount for the commercial spaceflight industry — commercial spaceflight providers are already trusted by the U.S. government right now to launch multi-billion dollar military satellites, upon which the lives of our troops overseas depend. And over a dozen distinguished former NASA astronauts, including Buzz Aldrin, published an op-ed a few months ago in The Wall Street Journal stating that commercial companies can safely handle the task of low-Earth orbit transportation.”

Rocky Mountain High Altitude

The fact that two of the CCDev awards went to Colorado companies underscores its claim to being one of the most aerospace-centric of the 50 U.S. states. Denver-based United Launch Alliance (ULA) is a joint venture of Boeing and Lockheed formed several years ago to manage rocket-launch operations for the federal government. ULA program management, engineering, test and mission support functions are headquartered in Denver. Manufacturing, assembly and integration operations are located at Decatur, Ala.; Harlingen, Texas; and San Diego, Calif. Launch operations are located at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla., and Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif.

ULA was awarded $6.7 million to develop an Emergency Detection System (EDS), which “is a significant element necessary for a safe and highly reliable human rated launch vehicle,” according to the company. The EDS monitors critical launch vehicle and spacecraft systems and issues status, warning and abort commands to the crew during their mission to low Earth orbit. ULA studies show that the development of the EDS will help meet the requirements for human rating the Atlas V and Delta IV launch vehicles.

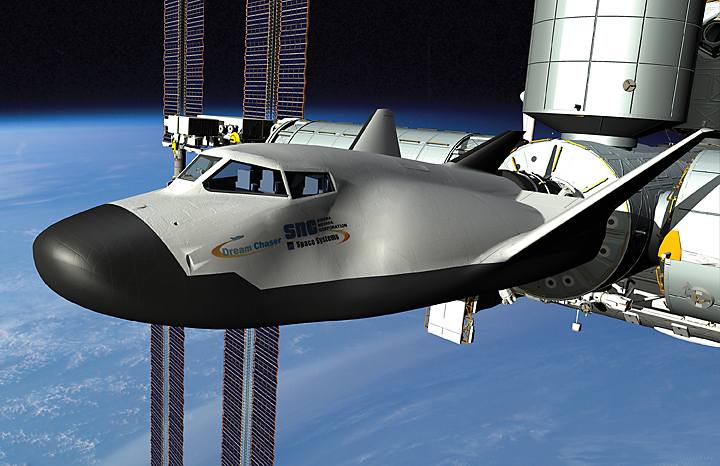

Sierra Nevada Corp. (SNC) is headquartered in Sparks, Nev., but its Colorado operations manage its space programs. SNC’s $20-million CCDev award, the largest of those announced in February, will further development of the winged and piloted Dream Chaser orbital commercial spacecraft that will carry six passengers. The craft has been in development for several years, first at SpaceDev, which is now an SNC subsidiary. The company is active in several other aerospace initiatives, as well, leading to expansion activity in Centennial, near Denver, among other projects. The 200-job Centennial expansion, for example, announced in December 2009, involves an operation that customizes aircraft for specific uses by the U.S. government, such as border patrol.

Under-the-Radar Work in Colorado

“In December 2008, we merged with Sierra Nevada, an existing aerospace company that did not have a space operation,” says Mark Sirangelo, former chairman and CEO of SpaceDev, who now is SNC corporate vice president overseeing the Space Systems Group. Sirangelo also serves as chair of the Commercial Spaceflight Federation. “We have merged three space companies together to form a fairly large space operation.”

Besides work on the Dream Chaser, SNC’s space group produces small satellites that can be mass produced and networked in space. A corollary was the transition years ago in the computer world from mainframe computers to laptops and PCs linked by wide and local area networks.

“There’s a whole new sector of space opening up by virtue of smaller satellites that are networked in space, and we’re a leader in that sector,” says Sirangelo. “We’ve recently built and opened our latest manufacturing facility in Louisville, between Boulder and Denver, the first to build small satellites in an assembly-line capacity. In the past, satellites were built in a one-off way, where each is a singular project. Now we’re thinking about constellations that are in the dozens or hundreds of satellites working together.” The Louisville location, where Sirangelo is based, provides “a nice mixture of being between the university-centric Boulder and Denver, which has been a good source of talented people for us.”

SNC is also a major manufacturer of components and subsystems — the guts of larger space programs, including the Mars Rover robotic space missions and work on large satellites. The company finds itself in early 2010 in expansion mode in more than just one area, though work on the Dream Chaser with its recent federal funds infusion will be fascinating to watch.

“At the end of the day, NASA will have two or three companies they can call on to essentially act as the contract operator to bring people to the space station and to return product from the station and do things in orbit, as opposed to NASA owning and developing the vehicle itself,” says Sirangelo. “It’s a very nascent part of the business, but NASA clearly made a big statement recently when they cancelled their own programs in space and announced a movement to this outsourcing concept.”

About one quarter of SNC’s 2,000 U.S. employees are in Colorado, up from about 100 just a few years ago. Not only is the aerospace sector in growth mode there and elsewhere, says Sirangelo, but demand for new systems and solutions will keep it that way for some time.

“Space as an ‘enterprise’ is sometimes not viewed in that way,” he says. “But as in most industries, there are opportunities to re-imagine how things can be done, much like the computer revolution re-imagined technology in the 1980s and ’90s.” A good example in aerospace is the growing importance of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), which are increasingly sophisticated and effective in observation and military missions.

“Ten years ago, we didn’t have any UAVs, and now we can’t get enough of them,” says Sirangelo. “People said they couldn’t do the jobs of pilots, and now they are doing many of the jobs done by pilots. Industries go through that, and we find ourselves in that position in the space sector in part because there aren’t the budgets to do things as they were done before. You’re forced by necessity to look at how you can do things differently. We’ve been fortunate to be positioned in a couple of those areas that are getting a lot of attention these days.”

A Booster Rocket Role for the State

The sector’s growth is hardly lost on state officials. In fact, aerospace has long been a target industry for Colorado, which is home to several national science facilities, top aerospace engineering programs and the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. Among the state’s scientific resources are the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder and the Dept. of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden. Lieutenant governors, including current Lt. Gov. Barbara O’Brien, routinely champion aerospace initiatives, whether the sector is part of their background or not.

“Lieutenant governors all over the country got involved in aerospace after [the launch of the Soviet Union’s space program] Sputnik,” says O’Brien, whose background is in health and education. “The Department of Defense and the aerospace industry thought that if they started building relationships with lieutenant governors, they would be making contacts with people who would be future leaders. In Colorado, we’ve taken that very seriously, and it’s been a tradition that the lieutenant governor, whichever issues he or she runs on, picks up aerospace as a priority and co-chairs the Colorado Space Coalition.

The Coalition works to discover and cultivate synergies where Colorado’s military, commercial and higher education research sectors overlap. Frequently, the aerospace sector benefits from that work. “We’re not promoting any one corporation over another,” says O’Brien. “But where we find those synergies we can then go to our congressional delegation with policy changes we’d like to see done, or we come to our state legislature to see if we can get seed money for start-up projects. It’s really about the way those three parts of our state intersect for the benefit of aerospace,” which is one of the top five industry priorities of Gov. Bill Ritter’s administration.

Challenges to Overcome

Colorado, like many states, faces two challenges in keeping the aerospace sector thriving and competitive — immigration and U.S. government ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations) controls governing the export and import of defense-related technology, particularly in the wake of 9/11. Many in the commercial aerospace industry consider ITAR policies to be too restrictive and an impediment to their ability to compete effectively in the global marketplace.

As for immigration, Colorado aerospace companies and those in other locations have reservations about finding and keeping the highly trained engineering graduates they need, especially with relatively fewer U.S. students entering the field and fewer non-U.S. students being permitted to remain in the U.S.

For now, says O’Brien, state higher education is meeting the needs of state employers. “It’s the future that all the states are worried about, and competitiveness with other countries,” she says. “At the moment, the University of Colorado at Boulder receives more NASA funding than any other university in the country. So they are big in aerospace and have an outstanding aerospace engineering program. The main employers say they are finding highly trained engineers coming out of our schools. What we’re worried about is what happens with the kids in school now, where math scores are stagnant and fewer kids overall in the U.S. are going into engineering as careers. It’s the future pipeline that is of concern because of the visa issue. It’s harder and harder to keep students here when they graduate and their time as students ends.”

For now, Colorado’s private-sector aerospace industry employs about 26,000, and as many as 170,000 work in aerospace-related jobs in more than 300 companies, says O’Brien. How those numbers will hold up in the coming years remains to be seen.

No Space Background Required

For the time being, Sierra Nevada’s Sirangelo is having no trouble meeting his staffing requirements as his space operations ramp up. “Colorado has a high concentration of technology-savvy people and a well-educated work force, which is one of the key things to a growth industry like ours,” he observes. “We can’t necessarily find all the people with a background in what we do, because a lot of it hasn’t existed before. But we can find technologically-savvy people who have an interest in what we’re doing.”

Much of what SNC is doing involves first imagining and then developing and building all-new ways of expanding scientific exploration and understanding. “We have to do a lot of imagining about what life would be like on Mars,” Sirangelo illustrates. “We helped build the two Rovers, and we’re helping build a new science lab that’s going to Mars. With no one ever having been there, you have to have a good imagination about what it’s like. Much of that work is done through simulation, which is computer driven. A space background is not necessarily required to figure out how to simulate something — it’s much like computer gaming. We’re very fortunate in that the state has a good base of those people.”

Launching Talent and Innovation

Still, Sirangelo does not take that base of workers for granted.

“One of the downsides to aerospace is an aging population in our industry. To that end, we decided that, rather than wait for that to happen, we would do something about it. Working with the University of Colorado, we launched a nonprofit enterprise called the Center for Space Entrepreneurship, or eSpace (www.espacecenter.org), which is supported by government, the university and industry.”

One goal is to encourage high school and even grammar school students to become involved with science and engineering, and specifically aerospace, because that hasn’t been a much-sought-after field, says Sirangelo, “mainly because many of those kids don’t want to see themselves working in the bowels of a global aerospace company doing CAD work.

“But aerospace in my world is not really like that,” he maintains. “We’re doing some pretty interesting things. How often can you go home and say you landed on Mars? We found when we talked to students, they got excited, but there wasn’t really a mechanism for that to manifest itself, so working with the university we’ve created this program that tangibly goes out and gets students involved with work flow and work forces. They can come out and experience for six months what it’s like to work in a company like mine. It’s worked very well.”

Secondly, eSpace has established an incubator, says Sirangelo, where “nascent companies who are looking to do new things that might help our industry have a place where they can get support. We provide some early-stage funding, we provide mentors to help make that work, and we now have several companies in that pipeline and a lot more that will be moving to the next level. These are companies that one day might be run by people that someone like me calls upon if I have a problem and need to find a way to build a really small motor, for instance — how do I do that?”

The state, too, is helping aerospace startups become established, notes Lt. Gov. O’Brien. “A lot of smaller companies need help knowing how to get involved with the federal contracting system, so we created a procurement technical assistance center with federal funds,” she says. “We’re trying to really help this industry shoot forward.”