Updated insights from Novogradac offer evidence of the OZ incentive’s success.

The following analysis, published by special arrangement, is an adaptation of several August 2024 posts by Jason Watkins, CPA, a partner in the metro Atlanta office of Novogradac, with contributions from Novogradac Director of Public Policy and Government Relations Peter Lawrence. For more information, visit www.novoco.com.

With significant tax provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) set to expire next year, 2025 is being called the “Super Bowl of tax.” The opportunity zones (OZ) incentive was enacted by TCJA and while the capital gains investment deadline through this incentive does not expire until 2026, stakeholders are using the review of the TCJA to garner support for the extension of this deadline and other proposed enhancements.

The OZ incentive was created to encourage the investment of capital gains in underserved communities. OZs are census tracts in low-income communities experiencing economic distress. There are more than 8,700 OZs in the 50 states, District of Columbia and U.S. territories.

There are three main tax benefits to investors. The incentive allows investors to defer the payment of taxes on capital gains up to nine years, if those gains are invested in qualified opportunity funds (QOFs), the mechanism used to direct investment in economically distressed communities. For investments held for at least five years, there is a 10% step-up in basis, effectively reducing the deferred tax liability by 10%. For investments held for at least seven years, the taxpayer’s basis is increased by an additional 5% of the original gain. After paying the deferred capital gains tax, taxpayers holding investments for a period of at least 10 years are exempt from taxation on any additional gains. The ability to invest capital gains in a QOF ends in 2026, but legislation introduced earlier in the 118th Congress would provide a two-year extension.

Billions of Investment Dollars

Qualified opportunity funds (QOFs) tracked by Novogradac reported nearly a half-billion dollars in equity raised during the second quarter of 2024, putting total equity raised since the start of the OZ incentive at $38.3 billion.

The 1,479 QOFs tracked by Novogradac that report a specific amount of equity raised (Novogradac tracks another 418 QOFs that report no equity) accounted for an additional $446.9 million in equity raised in the period from April 1-June 30. QOF data reported by Novogradac doesn’t include proprietary or private funds owned and operated by their principal investors. It is estimated that actual OZ investment is up to three times greater than the Novogradac total.

Novogradac breaks QOF investment into five categories: residential, commercial, hospitality, renewable energy and operating businesses. The first two categories receive the overwhelming majority of investment, with QOFs focused on residential development only reporting $7.87 billion in equity raised, while QOFs with at least some focus on residential reporting $31.46 billion in equity.

Novogradac can account for 185,436 homes built with tracked QOF funding — it is estimated that this total likely exceeds 500,000 homes. Nashville, Tennessee, is the leader in homes built by funding from QOFs tracked by Novogradac, with 7,529 homes. Six other cities — Washington, D.C.; Phoenix; Austin, Texas; Cleveland; Los Angeles; and Charlotte, North Carolina — have seen more than 5,000 homes built with investment from QOFs tracked by Novogradac.

Commercial-only QOFs report $2.22 billion in equity, while QOFs with some focus on commercial have raised $25.71 billion. QOFs with at least some focus on hospitality have raised $4.12 billion, those with some focus on renewable energy have raised $2.23 billion and those with some focus on operating businesses have raised $1.14 billion. Each of those overall categories saw between $20 million and $50 million in new investment in the first six months of 2024.

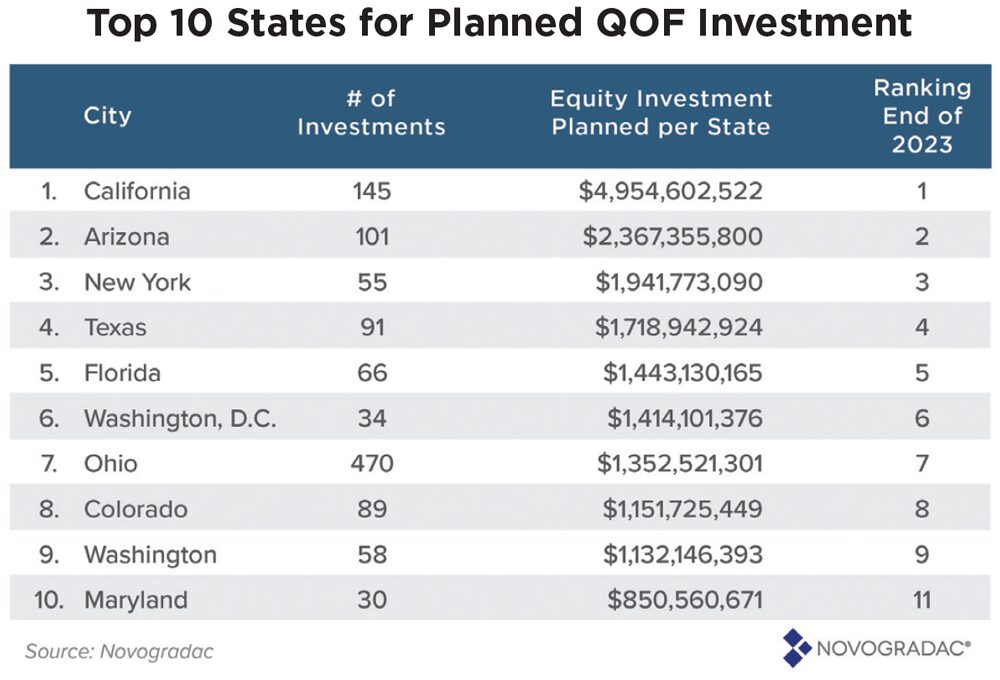

California remains the state with the most planned QOF investment, with an additional $878.7 million added in the first half of 2024, more than six times than in Nevada, the only other state that received more than $100 million during the same period. California has $4.95 billion in planned investment, more than double any other state.

The top nine states for planned investment remained unchanged since the end of 2023. Maryland moved past Tennessee into the 10th spot at midyear 2024. Among other states on the list of the top 20 states for investment, North Carolina moved from 13th to 11th and Nevada moved from 18th to 16th. Novogradac tracks planned QOF investments in 49 states, as well as the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico.

Los Angeles received $217 million in planned investment in the first half of 2024 (constituting 24.7% of California’s overall planned investment) to remain the city with the most planned QOF investment at $1.75 billion. Washington, D.C., and New York City rank second and third, ahead of rural Fresno and Kings counties in California, an unincorporated area that has seen $1.2 billion in QOF investment in solar power. Those three cities (and one area) are the only specific locations with more than $1 billion in planned QOF investment.

Among the rest of the top 50 cities on Novogradac’s list, the cities that moved up the most in the first six months of 2024 were Tempe, Arizona, (13th to 11th), Las Vegas (31st to 20th) and Richmond, Virginia (39th to 32nd). Novogradac tracks planned QOF investments in 335 cities.