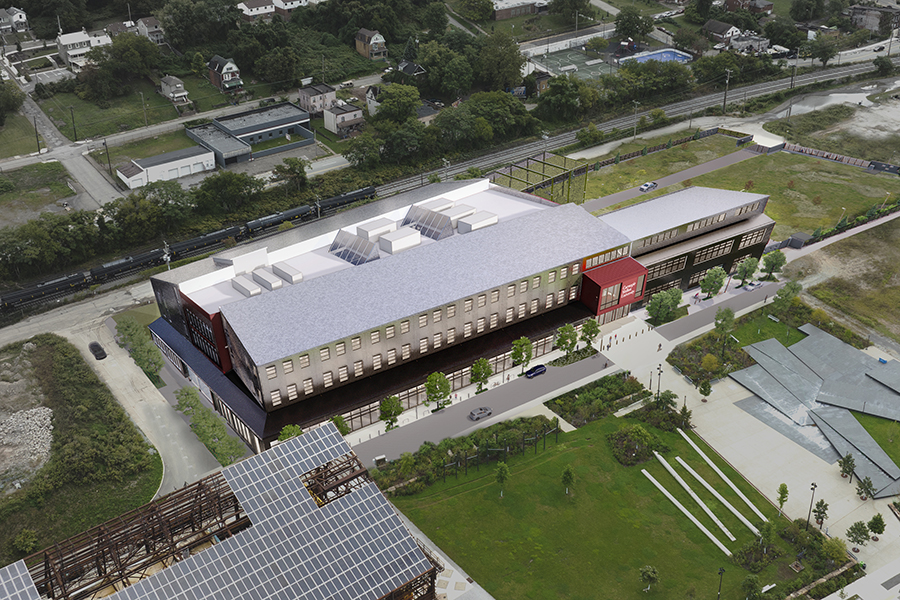

The revitalization of the Hazelwood Green site began with the former J&L Steel plant site, where the first phase of construction welcomed CMU in 2019.

Photo courtesy of RIDC

When it comes to a high profile in the worlds of artificial intelligence and autonomy, does Pittsburgh spring to mind? It should.

As a resourceful playground for the curious, the city has laid claim to technological breakthroughs dating back to the first proper AI program cultivated from the minds of Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) researchers Allan Newell and Herbet Simon in the 1950s. Over 70 years later, groundbreaking innovation is something of the norm throughout the western Pennsylvania region.

A New Vision for Hazelwood Green

As a first-time visitor, when my travels took me through the over-half-mile, warmly-lighted stretch of the Fort Pitt tunnel on my way to the revitalized Mill 19 complex, I felt like I was climbing the lift hill of a rollercoaster — simply anticipating what’s to come.

My drive into the 178-acre Hazelwood Green site was accompanied by views of the Monongahela River to my right, just as the sun began to peek through the trees — a great way to get creativity flowing in the morning. On arrival, it was hard not to notice construction activity taking place on the shell of BioForge, the University of Pittsburgh’s future 185,000-sq.-ft. biomanufacturing facility adjacent to the Mill 19 complex.

Construction continues on BioForge, a biomanufacturing facility purpose-built for the University of Pittsburgh.

Photo courtesy of the University of Pittsburgh

To be frank, photos cannot capture the true essence of how the Regional Industrial Development Corporation (RIDC) revived the former J&L Steel Hazelwood Works facility into 265,000 sq. ft. of dedicated space for robotics, technology and advanced manufacturing research.

CMU is the complex’s anchor tenant, serving as headquarters for the university’s Manufacturing Futures Institute, in addition to housing its Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing (ARM) Institute and the Catalyst Connection workforce training center. Currently, the space provides 60,000 sq. ft. of low bay and high bay project areas, additive lab space, collaborative workspace, meeting rooms and a machine workshop.

Construction is nearing completion on CMU’s $100 million, 150,000-sq.-ft. Robotics Innovation Center (RIC) adjacent to Mill 19, which is expected to open this fall. RIC builds upon the university’s National Robotics Engineering Center that was introduced in 1996 to attract robotics projects for commercial clients, such as the Department of Defense. This initiative will operate differently: Instead of focusing on specific client applications it will create a range of environments that supports a breadth of fundamental and applied robotics experimentation.

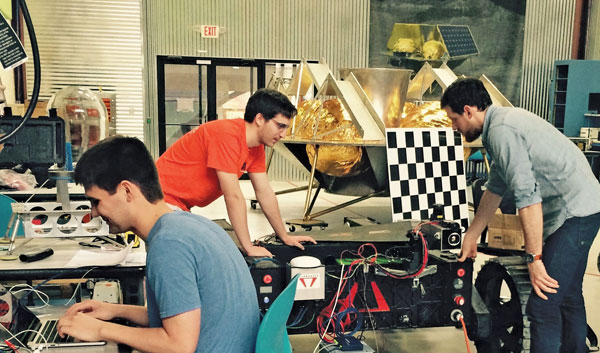

The Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute allows CMU to collaborate with industry, government and academia to enhance robotics utilization.

Photo by Alexis Elmore

“The model for RIC is based largely on the National Robotics Engineering Center, which is a part of the CMU Robotics Institute,” says CMU School of Computer Science Associate Dean for Strategic Initiatives Phillip Lehman. “The vision for RIC is the same, but much more open research and generalized robots, especially big robots. It’s fine to have a little lab on campus to build a small robot, but a lot of the work we do is larger.”

From agricultural robots to autonomous vehicles to interplanetary robots, diverse space needed to develop and test new concepts becomes vital, and hard to come by. Blueprints of RIC left me speechless.

“It’s a big playpen for robotics,” Lehman states.

He isn’t kidding.

The first floor will feature a high bay project area, including a continuous vehicle pass-through that leads out to a 1.5-acre outdoor running room. This 65,500-sq.-ft. space will emulate various outdoor terrains to move robots throughout, additionally incorporating a 6,000-sq.-ft. drone cage. Moving back inside, the facility will house an over 2,000-sq.-ft. water tank designed for underwater robotics, an open-layout wet lab and a 50,000-sq.-ft. indoor robot test space.

By fall 2025, operations at the 150,000-sq.-ft. Robotics Innovation Center will begin.

Rendering courtesy of Perkins Eastman

Collaboration is a key focus of RIC, which will host dedicated spaces for development, research and skills building. For early-stage robotics startups the facility will introduce fresh incubator space.

“We’ve already had a lot of interest from companies that are looking to partner with us on research, sponsor research funding and to share the space,” says Lehman, “So it’s really exciting.”

RIDC President Donald Smith says that real estate developer Tishman Speyer will soon break ground on 50-unit apartment building with a ground level that will bring new retail space to Hazelwood Green. Combined with a 2-acre green space and the future multi-sport recreational facility Hazelwood Stadium, this historic Pittsburgh neighborhood anticipates a new era of community development.

“We think that will be a big difference maker for the site, to have on-site services and have a little more 24/7 kind of vitality and sense of community,” Smith continues. “Development has been focused on the Mill District to create that sense of place first then expand out, so we’re excited to have that going up.”

Driving a Healthy Collaborative Ecosystem Forward

Over 20 robotics companies operate in what is known as Robotics Row in Pittsburgh, a number that was fewer than five when John Bares launched Carnegie Robotics in 2010. As a spin-off of CMU and NASA’s National Robotics Engineering Center, the company focused on commercializing autonomous applications for large OEMs and defense industries.

The RIC layout creates ample indoor and outdoor test environments for robotics, drones and vehicles.

Rendering courtesy of Perkins Eastman

“There’s a lot of persistence in Pittsburgh — I don’t think we give up,” says Bares. “We have continued to stay in difficult spaces of robotics where software meets hardware and then meets the real world. We’ve continued to tug startups, universities and larger companies to that spot. It’s really tough. I think that’s helped a lot of the reputation and the growth of Pittsburgh.”

Carnegie Robotics grew its capabilities quickly, eventually (and unknowingly) attracting a visit from former Uber CEO Travis Kalanick to the company’s Lawrenceville site in 2015. He first attempted to buy the company, later settling for an intellectual property deal for some of Carnegie’s information technology. Bares worked alongside the rideshare giant to develop Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group, which focused on self-driving technology for vehicles and which later was sold for $4 billion to nearby Aurora Innovation in 2020.

Following that period, Carnegie Robotics shifted to autonomous applications within agriculture, mining, construction, marine boat and defense industries. On a walk through the facility with Carnegie’s Chief Development Officer Mike Embrescia, I got a look at autonomous models of vehicles, construction trucks, boats, floor scrubbers and even a radiation-detecting robotic “dog” whose eyes feature a specialized camera and sensor system the company created for Boston Dynamics.

Carnegie’s partnerships can span months to years when developing new technology, although when working alongside industries like defense, time is of the essence. When technology and management consulting firm Booz Allen sought to address challenges such as overheating, affecting battery packs carried by U.S. soldiers, it turned to Carnegie for results when an industry-leading manufacturer could not deliver.

“When you talk about speed, this is a great example,” says Embrescia. “They said they couldn’t afford to wait anymore, so we started talking to them in April 2024. By the end of May we had a prototype ready and were selling them by fall.”

Carnegie’s workforce stands at 170 employees today, many of whom were scattered throughout the facility locked in on various projects as I looked around. Embrescia says with activity on the rise, plans are in the beginning stages for a future facility expansion that would deliver an additional 20,000 sq. ft. of workspace.

Established and homegrown companies including Caterpillar, Bosch, Honeywell, Gecko Robotics, Astrobotic, Aurora Innovation and more now fill Robotics Row. Such proximity has opened doors for innovative collaboration, but more importantly has kept tech talent and skilled graduates from CMU and the University of Pittsburgh concentrated in the region. Today, Pittsburgh remains a top destination for tech talent and supports a growing number of over 13,000 industry-related jobs.

This archive photo shows Astrobotic staff building the Griffin Lander using parts source almost exclusively from Pittsburgh-based machine shops.

Photo courtesy of Astrobotic

At an AI Horizons Pittsburgh Preview Summit held later that day at self-driving technology company Aurora’s HQ, local founders delivered an inside scoop as to what has kept their operations in the city. John Thornton, CEO of aerospace robotics company Astrobotic, was able to spin his startup out of CMU about 18 years ago and despite his niche operations, has remained solid in Pittsburgh.

“A lot of people thought we were crazy building a space company here in town, but we stuck to it. The town believed in us,” he says. “We ended up winning upwards of $600 million in NASA and related contracts. Now, we’re headed to the moon.”

Right there on Robotics Row, the Astrobotic team and California-based Venturi Astrolab constructed the Griffin lunar lander, a vehicle crafted with 99% of its parts coming from Pittsburgh-based machine shops. (See this November 2015 story in Site Selection documenting the lander’s construction.)

Griffin will make its way to the moon next year to explore its south polar region, a critical mission to discover what kind of materials are located here. Thornton notes that the moon is a vital resource for advancing space activity. In the case of water mining, robots can be used to locate deep deposits of frozen water on the moon to be split, condensed and used as rocket fuel.

“We are in a race with China and other adversaries that want to do the same activities,” says Thornton. “We have an opportunity in Pittsburgh to build on our groups of energy, robotics and now groups of space to actually go and capture this new domain and open an entire new frontier.” (Read this September 2023 Site Selection story about Astobotic’s lunar ambitions.)

Founders — including Bares, Gecko Robotics’ Jake Lossararian, Eos Energy’s Joe Mastrangelo and Abridge’s Dr. Shiv Rao — shared the same sentiments on Pittsburgh’s opportunity to lead the nation’s tech and energy revolution. Skilled talent, abundant natural resources, top research institutions and legacy industry expertise represent a few tools that continue to set the city apart.

“I think what Pittsburgh has is humility,” says Rao. “There is that ethic to Pittsburgh that I think everyone who’s born and raised here, but also everyone who moves here, can’t help but absorb.”

Abridge was created as an AI-powered platform designed to transcribe medical conversations and improve clinical documentation for doctors and patients. Rao built the company leveraging the city’s world-class health care and AI talent, although it did not locate on Robotics Row, but rather positioned on the city’s east end. Its operations are near the one-mile stretch from Bakery Square to East Liberty forming what is now referred to as AI Avenue. Anchor companies, including Google and Duolingo, converge with more than 20 emerging AI companies to form the city’s own AI technology hub.

No one knew what the fall of the region’s steel industry would bring for Pittsburgh, but the city’s determination to start anew has positioned the city to lead a “human-first” AI economy and become a powerful player in the Fifth Industrial Revolution.