Real estate and corporate resources executives from several leading financial companies gathered in New York City in mid-December 1998 to discuss ways in which they are helping drive change in their organizations. Unless an organization changes, it stops growing, becomes less competitive — even non-competitive — and will be left behind by more nimble players. This is particularly true in the financial services arena, where players invest huge amounts of money every day to remain competitive locally and globally. At the same time, few industries are as used to cutting costs when the going gets tough as financial services.

In order that the ax not cut too deeply into such strategic assets as human resources, work space and competitive information systems, the executives gathered for a working luncheon roundtable discussion at the Midtown Manhattan offices of E&Y Kenneth Leventhal Real Estate Group, a unit of Ernst & Young LLP. Their task was to share ways in which they are adding value to the complex process of matching physical assets to their organizations’ strategic plans and to articulate the corporate resources issues they face.

Discussion moderators were Barry M. Barovik, E&Y Kenneth Leventhal’s national director of corporate real estate services, and Mark Arend, senior editor of Site Selection Magazine. Discussion participants included: Stephen Bell, senior vice president, Fidelity Corporate Real Estate, Boston; Richard Lilleston, director, real estate, at Merrill Lynch, Princeton, N.J.; Cesar Chekijian, senior vice president, Chase Properties Group at The Chase Manhattan Bank, New York; Karla Schikore, president of Karla Schikore and Associates LLC Corporate Real Estate Consulting, Petaluma, Calif. (formerly a real estate executive at Bank of America); and Robert L. Hamilton, Jr., vice president, global corporate real estate at CIGNA Corp., Philadelphia.

Also attending the discussion were E&Y Kenneth Leventhal executives Joseph B. Rubin, partner and national director of the real estate group’s financial services practice, James J. Glennon, manager, New York corporate real estate services, and Peter S. Brooks, principal, corporate real estate advisory, special;izing in financial services. Following are excerpts from the discussion. Comments have been edited for clarity and space considerations.

Mr. Barovik (E&Y Kenneth Leventhal): Your introductory remarks reflect a variety of corporate structures where real estate services are concerned, from centralized to decentralized. Specifically, where do you and your objectives fit into the larger corporate organization?

Mr. Bell (Fidelity Corporate Real Estate): We have about 39 different companies at Fidelity, all of which have their own president. One of those companies handles real estate, which is a centralized function. If anybody has anything to do with real estate or management of hard assets, they have to work through us. We are a required service group, and we have outsourced much of what we do over the past four years. But we still have a fairly large in-house staff with a full complement of project managers and a team of information managers. One of the groups I manage is a workplace research group.

Mr. Barovik: Do you integrate [real estate] with technology and human resources?

Mr. Bell: We are a totally separate organization right now. I’m sure the group is familiar with

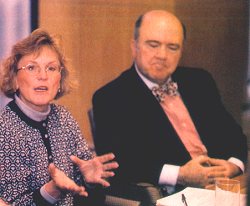

Below: Barry Barovik of E&Y Kenneth Leventhal (left) and CIGNA’s Robert Hamilton, Jr.

Mr. Hamilton (CIGNA Corp.): We have been taking an integrated approach for the past three years, primarily in our strategic planning effort. In retrospect, as we have tried to make decisions in real estate that support our environment, we were not doing it in a well-thought-out way. The life cycle of real estate and the technology life cycle were not along the lines of the life cycle of our business. So we introduced a new way of approaching these decisions. Twice a year we meet with the business heads and do a three-year projection of their changing business needs in terms of people, space, technology, public affairs, and legal considerations. We must demonstrate that this process enables people, space and technology to deliver their products and services more competitively and profitable than the competition. That is the objective. The focus is not the cost of real estate. It’s how that cost is an enabler. Do you know what your percentage of real estate cost is to your revenue right now? If you don’t know that answer to that, then you are still trying to understand what the cost of your real estate is rather than how it is an enabler.

To illustrate, CIGNA has a project in the works now called One CIGNA. It’s not real estate driven or technology driven; it’s business driven. The project is about selling our products and services, be they health care related, financial services or insurance, through one lens, not from [different people with different specialties]. The end consumer at the end of the day just wants to buy the right product at the right price. So we are reshaping our sales and marketing offices throughout the country, using technology to develop this business-driven entity called One CIGNA. Once the sales and marketing side of the project is in place, we will extend One CIGNA to the customer service side as well.

Mr. Brooks (E&Y Kenneth Leventhal): As mergers across industry lines proliferate, the issue of whether or not there is synergy among various products and whether you can capture [market share from such diverse clienteles] in one location becomes important.

Mr. Barovik: As you develop these strategies, are you encountering problems with the business units relative to control of the decision-making process?

Mr. Arend (Site Selection): Put another way, do you find you must deal with turf battle issues involving technology, human resources, corporate real estate and other business functions?

Mr. Bell: At Fidelity, cost is important, but on a scale of 1 to 10, it’s 11 or 12. We want the retail centers to be in the very best location and have the best technology available. We work very closely with the technology people and the human resources people on the Investor Centers [retail locations], because that’s what the public sees. As for other property — call centers, operations centers, corporate offices — cost is more of a factor.

Bob asked earlier about percentage of real estate to revenues. At Fidelity, real estate is a very low percentage of revenues. But cost is not the primary driver. It’s important, but the primary driver is making sure the business can work in its environment the best that it can. Enhancing the workplace is what we’re all about today and into the future. If you’re solely driven by cost, you’re headed in the wrong direction.

Mr. Chekijian (Chase Manhattan Bank): I disagree. As a private company you do not have the requirement to meet and exceed the expectations of existing and prospective shareholders. Public companies do. Then there is the issue of performance measures. The key performance indicators are a lot different than just supply-driven corporate real estate. We deal with the demand side — the expectations of the client, the business unit, the shareholder, the corporation. Corporate real estate must anticipate the expectation of the prospective shareholder and how to exceed it. The minute you define that you put yourself [in the context of] Wall Street. That is where you start: to solve to what it is that Chase can afford to spend in occupancy cost. The other components that drive the physical environment are people and technology, [which use] different key performance measures.

But we have to do that collectively. The total productivity of any public corporation is managed as total expense relative to revenue. The key word is relativity, not absolute dollars. The measures are demand driven and they are shareholder driven.

My point is a public company must increase its growth rate in earnings per share to exceed the multiples that it’s selling at. How you organize and deal with that is secondary. More and more we are finding that corporate real estate as a practice is shifting to exporting the execution [to outsourcing services and others]. The challenge for corporate real estate is [achieving] the leadership or management role. That is why you see the qualification of corporate real estate [executives] today being more on the finance and investment banking side than on the supply of buildings or building transaction side.

Below: Karla Schikore and Chase Manhattan Bank’s Cesar Chekijian

Ms. Schikore (KSA Associates): I agree completely. Most CRE executives are facing the question of how to add shareholder value in a unique way and [fully appreciate] the whole business perspective of the organization. I believe the finance models of the future will be completely different than those of today, where every business unit has its own model. The CRE can add value by pulling all those elements together to look at where corporate real estate can add value. So I agree that those organizations looking for corporate real estate executives today are first looking for good business people. They can find good real estate people, good property management people and good design and construction people. But they really need someone who appreciates the business perspective.

Mr. Bell: I’m not sure we are a long way apart. I would contend that the basic premise we have to work under is that we have to be cost effective. That is a given. We are a private company, and we are under a different set of pressures than those of you at publicly traded companies. Fortunately, as a private company we can take a longer view of some things we are working on. But I still think that if you’re not looking at the future in terms of both the demand and the supply side and figuring out how you can increase your company’s revenues, then you’re not doing the job.

Mr. Chekijian: That is true, but there is a higher meaning in what we are doing, which is to create value. Going into the next millennium, corporate real estate now has to be part of the value creation process, which means that it now has to talk in demand economics, in demand key performance measures. The supply is now being exported to people who understand the supply side performance measures. Our challenge is to marry the demand key performance measures and the supply key performance measures together to create value, and there is a tremendous opportunity to create value.

Mr. Barovik: We’ve all seen the rise in importance of technology and the chief information officer. What about the operational portfolio? How can we add value there?

Mr. Hamilton: Among other things, I look at how our businesses are changing, by redefining themselves or by acquisition or disposition. The challenge the chairman is putting on corporate real estate is: How well do you know your organization? So as we do an acquisition or a disposition and if you are part of that team, can you make the right decision faster and smarter than the competition? Most corporations have done a poor job in the absorption of other businesses. I’ve seen millions of dollars worth of real estate costs being left on the table when corporations have sold companies or acquired companies. We have to do a better job at that.

Another challenge we have as a real estate senior officer is to make sure our environments for people and technology are an enabler so as to obtain and retain the best and brightest people in the corporation.

Mr. Chekijian: Don’t underestimate what goes on in a corporation in dealing with merger planning. At Chase, corporate real estate played a key role in planning and anticipating mergers in advance. A significant amount of savings coming from mergers was from corporate real estate, in our experience.

Mr. Brooks: One of the things that’s happening in financial services with mergers is the emergence of different philosophies about sites and technology. Fidelity has 70 or 80 retail centers. Merrill Lynch probably has about 700, and Bank of America perhaps 3,000. As different business cultures merge, a key issue is how they view the necessity of physical locations as part of the distribution strategy.

Ms. Schikore: In the financial business, companies are trying to get locations to where the customers are. People want access [to financial services] 24 hours a day, seven days a week, where they want it when they want it. CREs are in a unique position to offer a new way of delivering the physical environment so that you can be first to market, and the first to get out when something doesn’t work – not everything works at the point in time when you think you need it to.

In the case of mergers and acquisitions, it’s interesting because you have two different cultures coming together that may have approached things differently. But regardless of what the culture is, if your physical way of providing a service is unique and different, and you can get the product or the business up and operating in a very fast time frame, then that is where you can really add value from a corporate real estate perspective.

Mr. Barovik: How are your organizations handling the retail delivery mechanism relative to the corporate and operations functions? Are multiple strategies at work or an integrated one?

Mr. Chekijian: The driver is not the location or the building. The driver is the customer and determining the best way to reach that customer. [Companies must first determine who their customers are and what services they intend to offer.] Then it’s time to design solutions with buildings and technologies, rather than designing the answer without really knowing what products and services and customers factor in.

Mr. Rubin: The trouble is, when you have such big companies as all of you do, and you are selling so many products to so many clients, how do you prioritize the location and type of retail outlet that you use? Demographics are changing, and customers’ needs are changing all the time. Customers are moving around the country, because they are aging, or because they their job requires them to relocate. But real estate is a fixed asset. You cannot just pick up a branch office and move it to Florida with your customers. How do you manage that portfolio of customers and make sure your distribution network is achieving that?

Below: Richard Lilleston of Merrill Lynch (left) and

Stephen Bell of Fidelity Corporate Real Estate

Mr. Lilleston (Merrill Lynch): Our focus in corporate real estate [at Merrill Lynch] is to work closely with the business units. Our various [internal] customers have real estate portfolios of leased property and owned property, and we try to manage those portfolios for them. The important thing is to give the business unit heads enough information and advice to make informed decisions. This represents a change in the way we used to work with them, which was to say, “You will or will not do this or that.” We’re listening to the business units a lot more.

Mr. Arend: How does your unit interact with other core functions, such as human resources and technology?

Mr. Lilleston: We are very focused on attracting and retaining the best employees, and we work with the human resources people on that. We try to keep costs under control and make assets as flexible as possible. If we sign a new lease, for instance, we make sure that the signing provision is not personal to us so we can get out of it if necessary. Perhaps this is more mundane than what others see the CRE role to be, but the direction is towards corporate services.

Mr. Barovik: How is technology helping you manage your real estate portfolio?

Mr. Bell: It depends on which business you’re talking about. The location strategy involving the Investor Centers incorporates systems that can pinpoint the right street corner or location according to demographics and all sorts of computer modeling techniques. Then, we hope we can find an available building there.

The strategy for the operations centers and larger facilities is different. It’s not just real estate that we look at. Among other things, we look closely at the cost of operations. If you move a department or group from Texas to New Hampshire, what will that do to your operational cost, head count, human resources cost, systems cost and taxes?

Mr. Barovik: What has been your experience with off-balance-sheet financing strategies?

Mr. Chekijian: Over the years, there have been a lot of exercises from investment banking and accounting [professions] for corporations to exploit their balance sheet. But none of them really addresses the P&L side of the equation. Now, corporations are looking for higher productivity and are pushing corporate real estate executives to see how they can reformat themselves to do that, and the spotlight is on the income statement. We’re looking to see how we can improve the cost of occupancy to revenues, and what we have to leverage is our balance sheet. It’s not to extract hidden values in the balance sheet – that doesn’t do anything to the P&L. In fact, it prejudices it, it puts it in the negative. It’s a mater of timing or modeling, of transforming corporate real estate and extracting it away from the corporations, removing what is there in the balance sheet, lowering the effect of the income statement and institutionalizing it in some sort of security that would have its own independent accountability and value creation. But the driver must be the lower effect of corporate real estate on the P&L.

Mr. Hamilton: Our businesses currently hold about $250 million in real estate per annum, and we manage it for them. We oversee how those dollars are being utilized. In the model we are working on, we would like to take the expense to a corporate level, allocate out the dollars. There are pros and cons. One idea is to sell a business off and if the company purchasing it wants to buy the real estate or lease the real estate from you, you can get the true value out as opposed to not really get the true value out.

Mr. Bell: I’m struggling with the fact that our cost of occupancy is such a low percentage of revenues – it’s around 3 percent. How much of an impact can I have on our total operations from a revenue perspective? P&L is a little different. It has a bigger impact on P&L, I agree. If we can have a major impact on P&L, then that is something to strive for. In terms of revenues, that is why we are looking at how to enhance the workplace to generate higher revenues for the corporation, because cutting costs is not doing it. That is not the right focus from a revenue perspective.

Mr. Arend: What additional pressures or considerations does globalization exert on your role?

Mr. Hamilton: We are trying to define: Are we a domestic company with an international division, or are we growing into a global organization? From a real estate perspective, people sometimes challenge me, asking why I want to know. Well, we have about 8,000 people in Philadelphia, where the corporate culture grew up, many of them – about 5,000 – in the One and Two Liberty buildings. That lease is up in ’06, and we must decide in December ’03 whether to renew. Can I reshape that decision to meet the prospective vision of what my corporation wants to be?

Mr. Chekijian: The overseas challenges are multiples of the domestic challenges we talked about earlier, because of the higher cost of doing business and narrower margins overseas.

Mr. Arend: Let’s look ahead three to five years. How will the profession be different? Will the moniker “corporate real estate executive” still apply? Will you or your peers be more involved in strategic planning for the organization?

Mr. Chekijian: You must demonstrate that you can create value-added in hard dollars – not qualitative, quantitative. The way to how we are going to do that is by dealing with the financial reporting, legal and tax aspects of

Ms. Schikore: If you think in terms of real estate being the workplace, whether you’re hoteling or you work from your car, it doesn’t matter – it’s where the revenue of the company is generated. That puts a different perspective on a lot of real estate organizations. Think as a business instead of just real estate specifically. This is where the business change of the future is going to be. I personally believe that corporate real estate won’t be here in five years. There will be something, perhaps corporate infrastructure, but it won’t be defined as CRE.

Mr. Lilleston: I hope somebody will know something about real estate, no matter what they call it! But I agree with that view. Real estate’s role, although still important, will be less of a driver [relative to] the corporate services function.

Mr. Bell: As others have pointed out, it’s going to be a combination of the major service provider units. I don’t think corporate real estate will go away in five years. Even though the fastest part of Fidelity’s business in terms of growth is the Internet, we will still have workspaces and environments that someone will have to manage.

SS