“Federal policy is causing us to lose more jobs than the disaster itself.”

With those words, Louisiana Economic Development Secretary Stephen Moret summed up the mood of the Gulf Coast region in the wake of the lingering BP oil spill disaster.

While communities in five states await word on when the leaking well will finally be capped — and when the cleanup effort will finally gain momentum — leaders in both the public and private sectors aren’t mincing words.

“In terms of dollars and jobs, the net effect of the deepwater drilling moratorium is greater than anything else, because of the multipliers and capital investment being lost,” Moret told Site Selection in late June. “We expect to lose 3,000 to 6,000 jobs within a few weeks and then up to 10,000 jobs in a few months. It could go up to 20,000 in 18 months.”

While a federal judge lifted the moratorium imposed by the administration of President Obama, lingering uncertainty over appeals, other proposed federal restrictions and delayed permits has brought drilling for new oil in the Gulf to a virtual standstill.

Now in its third month, the unstopped flow of oil into the Gulf caused by the Deepwater Horizon well explosion has galvanized economic developers throughout the region into adopting a multi-faceted call to action. Based upon a series of interviews with key leaders at all levels of business and government leadership, here is what the people in the region tell Site Selection they want to see happen:

- They want the federal government to stop making the situation worse.

- They want the American public to see that the Gulf Coast region is resilient and committed to a full recovery.

- They want tourists to give the region a chance to show that it can still shine.

- They want BP to do all it can to make the situation right, and that includes helping first those who need the help most.

“We have dramatically improved the state’s disaster response and recovery activities over the past 18 months,” says Moret. “We created a new Louisiana Business Emergency Operations Center. We are working closely with businesses and Homeland Security. And we are dedicated to helping businesses prepare for and deal with disaster recovery. We have activated this new center to deal with the oil spill situation, and we are committed to helping the economy recover after this event.”

Guessing Game: Measuring the Spill’s Impact

The challenge is accurately predicting the extent of the economic impact.

Hard numbers are hard to come by, but several groups are trying to estimate the spill’s economic impact. The CoStar Group estimates that the spill may depress coastal property values in the Mississippi Delta region by 10 percent over three years, resulting in the loss of $4.3 billion in property value.

Others take a less draconian view. NAI Global released a report in late June predicting that the oil spill would have only a minimal impact on the commercial real estate markets along the Gulf Coast.

The World Resources Institute estimates that commercial seafood production could decline anywhere from $350 million to $875 million over 20 years, based upon an analysis of fishery habitat in the 38,000 square kilometers (14,672 sq. miles) affected by the leak of up to 60,000 barrels of crude oil per day.

The most immediate concern for folks along the Gulf Coast, however, is the livelihood of tens of thousands of oil workers.

According to Dr. Loren C. Scott, one of the leading economists in Louisiana, “the impact will be mainly on the drilling rigs, but I do not expect long-term consequences from this spill. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita caused shutdowns in production, but this situation is entirely different. What happens after the moratorium is anyone’s guess. If this episode results in more regulation of the oil industry and higher costs on drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico, then you will get less of that activity, not more of it.”

Scott predicts that 30,000 to 35,000 oil industry jobs will be idled for up to six months because of the ongoing disaster and policy aftermath.

Morgan Stanley has even placed odds on how long the drilling shutdown will continue. The firm says there is only a 5 percent chance that new drilling will be back on line within six months, but notes that there is a 60 percent chance the rigs will be exploring for oil once again within 12 to 18 months.

Currently, some 33 deepwater rigs in the Gulf have suspended operations. Together, they employ about 9,000 workers.

John Hofmeister, former president of Shell Oil Company and the leader of a new Houston-based task force responding to the crisis in the Gulf, tells Site Selection that “the most important thing to do is get that well stopped and get the cleanup under control. Until we get that well stopped and the cleanup under control, we will see elected officials getting involved. They are so aggravated about this well not getting capped. But we must recognize that there will come a point when the well is stopped and the oil is all cleaned up. The key question then will be this — where do we go from here as a country in terms of the risks we are willing to take to have access to energy?”

Hofmeister says that this issue “has galvanized the oil and gas industry. The industry is coming together to put a number of task forces in motion to put together appropriate responses — well design standards; collective cleanup possibilities; safety management opportunities; and improving the overall performance of the industry.”

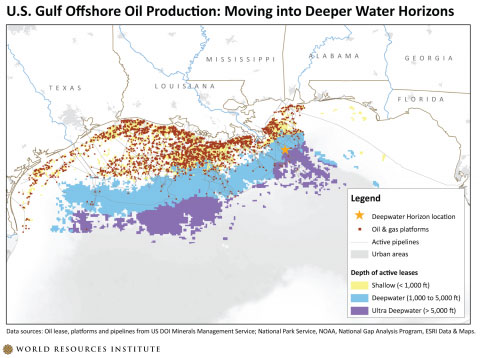

About a third of America’s energy production comes from offshore sources, and the reality of today’s energy environment is that the best locations for finding new crude oil are 5,000 feet or more below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico.

In the meantime, Hofmeister says he will help the Greater Houston Partnership spread the word that Houston and other Gulf Coast communities are still open for business. “We want companies to know that they have a business organization right here that is willing to look out for their interests, even if it means taking on the political flavor of the day, because we are looking out for the interests of the region as a whole.”

What’s at stake, besides lost tourism dollars, are a $2-billion commercial fishing industry in the Gulf, a $30-billion offshore oil industry and an estimated $100-million recreational fishing industry.

Dr. Peter Ricchiuti, assistant dean at the Freeman School of Business at Tulane University in New Orleans, predicts that both the fishing industry and the offshore oil industry will take a big hit.

“A lot of people will be affected,” he says. “We will see a lot of short-term layoffs in both the oil fields and the fishing business. And keep in mind that many people work in both industries. The sad thing is that this disaster comes at a time when there was so much positive momentum. I have been here for 25 years and I have never been more bullish on the region. We had 44,000 applicants for 1,600 freshman slots at Tulane this year. We were really starting to feel our oats.”

Ricchiuti says that, despite this setback, “there [will] be a lot of positives for the oil industry. They can’t end deepwater drilling permanently. Only one area has deep reservoirs of oil and that is the deepwater of the Gulf of Mexico. As bad as this situation looks right now, and as tragic as it was that 11 people died, we need to remember that these deepwater wells are technological marvels and they are incredibly safe. In the long run, there may be a lot more money spent on safety and regulation in the Gulf.”

Short-term, he says, the results could be “devastating. Some 15 to 20 percent of all jobs in Louisiana are tied to the offshore oil industry. Basically, that industry is going to come to a screeching halt for some time. These people likely will be laid off for several months. And it is really bad news for the companies. Some of these really highly skilled employees may leave and not come back, and they may go to other fields. The companies can’t afford to keep everyone on the payroll.”

Where Will Rigs Go? How Much Will BP Pay?

Another question is how many of the oil rigs in the Gulf will pull up stakes and move to other parts of the world to drill? No one really knows, but most economists tracking the Gulf Coast region say that such relocation is inevitable if the rigs remain dormant for long.

“Everyone is trying to figure out the winners and losers in all of this,” says Ricchiuti. “Companies that own the offshore supply vessels are being beaten down. One thing that may happen temporarily is that some of these boats and rigs may go to where the demand is now – Brazil and Nigeria. It is a pain in the neck to ship a rig to Nigeria, but they will do that if necessary.”

In the meantime, says Ricchiuti, “everybody in New Orleans and Houston is scrambling today to figure out what they can do.”

One of those scrambling is Secretary Moret, who says the administration of Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal will leave no stone unturned to rectify the situation. “We are preparing for the long term here at Louisiana Economic Development,” Moret tells Site Selection. “We are requesting [that] BP pay for a seafood certification program and marketing program to reassure people that our seafood is safe. We have to assure confidence in that. We are working on long-term economic recovery, anticipating a day when the spill will be stopped and the cleanup will begin. And we are looking for dollars to help offset job losses that have occurred.”

Moret notes that the impact on the seafood industry “has been the most severe. The seafood industry is receiving loss of income payments from BP. Tourism right now is experiencing a moderate effect. Louisiana doesn’t have a large portion of tourism focused on coasts, but we are seeing some drop-off in recreational fishing.”

So far, the state has received $18 million from BP to use in tourism marketing, but more is needed, says Moret.

How much total help will be forthcoming from BP is still in question. The company has set aside $100 million to help offset lost salaries caused by the drilling moratorium and agreed to set up a $20-billion fund for future restitution claims.

Despite the crisis, Moret says that Louisiana actually remains on track to have “an even better year this year than we did last year. We are in the final stages of several major economic development projects, and we are on track to close out 2010 with even more capital investment projects than we landed in 2009.”

The feedback from corporate real estate executives and site selection consultants has also been positive but measured so far. Pete Garra, director of real estate for North America for The Linde Group, tells Site Selection that the BP oil leak has had no impact at all on Linde’s gas operations in the Gulf. Michael McDonough, director of corporate real estate for international shipping giant Maersk, said that, so far, the Gulf oil spill had not adversely impacted his company’s shipping operations in the Gulf Coast region.

Prominent Chicago-based site selection consultant Ron Pollina says that, “from a corporate perspective, the oil spill probably is not affecting most companies in the Gulf Coast area. Still, there is the whole issue of the disaster and the perception that can be created in its aftermath. New Orleans is still recovering from Katrina. The state of Louisiana has made a lot of progress and has improved its business climate [http://www.siteselection.com/features/2009/jul/Louisiana/] since then. But there is still the question of lingering perceptions. This is really more of a perception problem than it is a real problem for most companies right now. Unless you are in fishing or shrimp or the oil business, it is not really affecting you.”

Experts See Opportunities After Disaster

Mark Sweeney, principal of McCallum Sweeney Consulting in Greenville, S.C., says that after the initial anxieties over the spill wear off, “if the oil is down there in the Gulf, they are going to stay there and eventually get to it. They will push the policy to allow for the drilling to gain access to that oil. So that industry will bounce back. Tourism is going to be iffier, because of lingering concerns over the water quality and related quality-of-life issues. Houston will be okay, and so will the vast majority of Louisiana [http://www.siteselection.com/features/2010/mar/SW-Louisiana/].”

John Boyd, president of The Boyd Company Inc., location consultants in Princeton, N.J., predicts that “the region will become a working laboratory for disaster recovery and remediation of the environment for years to come. The region will stand to attract some high-end life-science firms in coastal management and the environment, but at far too great a price.”

Paula Scalingi, president of The Scalingi Group and consultant to the newly formed Gulf Coast Alliance, says the entire region must work together “to respond and recover. Everyone in this region must work together to map out how things will look in the future once this disaster is over and all the oil is cleaned up. One lesson we all need to learn from the oil spill is that the unexpected does happen.”

Scalingi says “it is critical to measure the economic impact and respond accordingly. If you are looking at damage to businesses, there is no easy way that businesses can get compensated. Individuals can get compensated by FEMA, but businesses are pretty much on their own. There needs to be a better way for businesses to get compensated for their losses. We have to figure out how that can get done.”

She added that the key question is “how can we get the Gulf region back on its feet as quickly as possible? There will need to be a lot of investment into the Gulf region so that states and communities can move forward.”

Chris Laborde, a senior New Orleans Regional Transportation Management Center official and one of the leaders of the Gulf Coast Alliance, says it is important for all Americans to remember that “the Gulf of Mexico is home to nearly 4,000 rigs and platforms — the greatest concentration of artificial reefs, woven in with the energy hub of the Southeast.”

Laborde calls the current situation the “perfect economic storm,” but he adds, “We will overcome this challenge, and I believe the Gulf Coast Alliance will play a role.”

Because of the region’s importance to the national economy, Laborde says it is imperative that government assistance funnel into the region to help local communities and businesses rebuild and recover.

“We need more SBA loans, Gulf Opportunity Zone bonds and other forms of assistance,” he says. “What we don’t need are more drilling moratoria.”

Jeff Moseley, president and CEO of the Greater Houston Partnership, concurs. “The market just doesn’t work well with uncertainty,” he says. “It works even with bad law, but it doesn’t work with uncertainty. Business decision-makers are risk averse, and when government actions raise questions, that is when we have deep concerns.”

What’s Next for the Gulf Coast Region?

While the experts try to sort out the damage and estimate recovery costs, the International Economic Development Council has offered its own assistance to help the region rebound.

“We have just put together a proposal to send assessment teams down to cover a whole number of counties from Louisiana to Florida,” says Jeff Finkle, president of IEDC, a Washington, D.C.-based association that represents economic developers around the world. “It does not look like this crisis is hitting Texas. But we will be conducting these community damage assessments in conjunction with the U.S. Chambers of Commerce and the National Association of Development Organizations.”

IEDC is working closely with the Economic Development Administration to formulate a comprehensive economic recovery package for the Gulf Coast. Finkle says the group will consult very closely with economic developers in all of the affected communities.

Among the questions being asked, notes Finkle, are the following:

- How have coastal communities been impacted?

- What do people in the region think the federal government should do?

- Would governmental intervention be displacing some of the responsibility of BP to make things whole again?

- What should be the clear and definitive response of the federal government?

“We need to think of this like a natural disaster,” adds Finkle. “The communities will take the same ebb and flow that a natural disaster normally takes. They will go through a bust and boom. And as the recovery money starts to show up, there will be a spike in employment.”

The main issue holding up progress right now, he says, “is a fair amount of uncertainty. I talked to an LSU professor. His wife is a helicopter pilot who flies people out to the oil rigs in the Gulf. She is now unemployed. She is currently angry at the president because of the moratorium on deepwater drilling. It all depends on your perspective. If you later get made whole, your anger will get dealt with and the injured parties will be satisfied.”

Finkle says the silver lining in this disaster is the fact that “this industry has a lot of money. BP’s money will go a long way toward making people whole. It will help people who lost their jobs.

“The bottom line,” he notes, “is that the entire recovery process must be followed one step at a time. It just takes some retooling, some time and some planning to get through it.”

Moseley remains optimistic that, in the end, the right things will be done to correct this situation and avert another crisis. “It is going to cause all of us to be creative and look for ways to work together,” he says. “There will be a solution, and then our entire focus will be on cleaning up and moving on.”