LLocated in County Fife across the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh, Dunfermline is known as the ancient capital of Scotland. In recent months it’s made great strides toward reclaiming that crown, at least in economic development circles. And it’s leading a broader Scottish charge to claim the title of wind energy hub.

In December came the news that the 13-year-old white elephant semiconductor manufacturing complex originally built by Hyundai, then put on the back burner by Motorola and then Freescale Semiconductor, finally was sold to U.K.-based Shepherd Offshore Services Ltd. after three years on the market.

Doug Barrett, principal at Seattle-based ATREG (Advanced Technology Resource Group), says it was the only sizeable property transaction to have occurred in Scotland since the fourth quarter of 2008, and credits the marketing efforts of Colliers International, as well as the cooperation of planning councils in County Fife. ATREG spun off from Colliers in September 2010.

The 1-million-sq.-ft. (93,000-sq.-m.) campus comprises a large cleanroom shell designed for 200-mm. wafer processing with potential to convert to 300-mm. wafer processing, an office area, a central utilities building, and a water treatment plant. Officials at Shepherd declined to respond to repeated requests for interviews, but have sent signals that the property may become an energy park to serve the growing wind energy and other energy industry activity in the North Sea, and potentially be home to as many as 2,000 new jobs.

Scots will believe it when they see it. That was the same number of jobs Hyundai promised 14 years ago.

Danny Cusick, president of the Americas, Scottish Development International (SDI), says the Hyundai project came along at the tail end of a boom in the industry, at a time when “30 to 35 percent of all Europe’s personal computers were made in Scotland. Thereafter, industries and companies looked at offshoring. It disappeared almost overnight.”

Breakthrough at Last

Barrett says it takes some patience to move this type of property these days. “There are definitely headwinds for these types of facilities, especially when so much of this manufacturing has gone overseas, particularly to Asia.”

ATREG is representing Austin-based Freescale in marketing efforts for other sites, including a fully operational facility in East Kilbride, Scotland; and two others in Sendai, Japan; and Toulouse, France. The Dunfermline site was unusual in that it never reached operational status and was marketed purely for adaptive reuse. “The carry costs were relatively low,” says Barrett, “because of not having to keep the facility in any clean state, which can often be many millions of dollars per month.”

Three years ago when ATREG first took on the assignment, there were more than eight initial bidders, none of them semiconductor companies. Then the capital markets collapsed. Most recently, ATREG had entered advanced negotiations with a thin-film solar company, which Barrett describes as a perfect match for old chip fabs, given the match between “really tall and really heavy” product and chip fabs’ typically advanced floor structures and high ceilings.

The deal never went forward though. And most recently, advanced negotiations with California-based project development and management firm Zoom Diversified collapsed when Zoom was unable to close on all of its project funding for the facility conversion.

Disposition Dilemma

Semiconductor campuses, whether fully operating, partially operational or mothballed, usually represent many hundreds of millions of dollars of investment. “There are a little over 1,300 of them in the world that we’re tracking,” says Barrett. “They started in the U.S. with the rise of the semiconductor industry, then broadened into Europe, and now a lot of the manufacturing is happening in China and Taiwan, but also now in India and Brazil. From our standpoint, we really do see the global economy at work here.”

Because they’re so expensive to operate, the fabs have migrated to lower-cost regions, says Barrett. “It’s not necessarily a savings in construction, but mostly in labor costs, and especially in incentives. That’s where we see it’s difficult for the U.S. and Europe to compete. We just don’t offer the same incentives,” as say, Singapore, which Barrett puts at the top of the list.

There are very few buyers for the facilities left behind, he says, but it helps when firms such as ATREG can get involved when the facility is still operational and employing people, such as at East Kilbride.

If the facility is shut down, however, the alternative energy and data center industries are the strongest prospects for adaptive reuse, due to the infrastructure left behind. For solar firms, it’s the floors, high ceilings and water volume, as well as the fact that the equipment can be reused to make silicon panels. Data center proprietors like the air handling and cooling capabilities, backed by significant power loads. Barrett cites an example of one bankrupt memory company that just sold a 300-mm. facility in the U.S. to a data center developer, with the equipment sold separately to another U.S. end user. “For once it’s not going to Asia,” he says.

The market for that equipment is very robust. And that’s where the tension lies.

“From an advisor’s standpoint, we’re trying to say, ‘Keep the equipment on the floor, and look at selling it operationally for at least a few years before you have a shutdown.’ From an operations standpoint, the companies are going to look at the equipment first and think they can use it for their own internal needs. Second, they know the market for the equipment to third parties has traditionally been very strong, so it’s much easier [to do]. Generally that equipment tends to go to Asian locations, though not always.”

Though never started up, the Dunfermline fab was packed with advanced equipment, including boilers, chilled water plants, compressors, a couple dozen power generators and hundreds of industrial pumps. Most of that equipment was auctioned in January, after the sale to Shepherd, by Netherlands-based industrial auctioneer Troostwijk.

Right Time

Shepherd leaders never sought out assistance from Scottish Development International nor Invest in Fife for their investment, instead taking their proposal straight to Fife’s elected officials. Nevertheless, their plans fit in well with the plans of Scotland, Fife and the entire U.K.

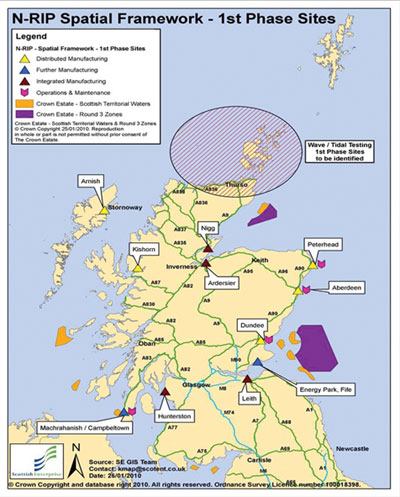

SDI’s Danny Cusick says Shepherd is coming on board to take advantage of opportunities generated by three offshore wind farms expected to generate 32 gigawatts of power. “Twenty-seven of those gigawatts are in the North Sea, and Scotland will take a significant portion of that,” he says, noting forecasts for many more to come over the next decade. “It’s estimated Scotland has about 25 percent of the wind resources for Europe. We estimate that 1,300 offshore structures will be required to generate that capacity, receiving between £18 billion and £25 billion of capital expenditure.”

One of several energy parks is a 134-acre (54-hectare) site in Methil, Fife, which has seen regular funding from the Scottish government and the EU over the past several years. On January 20, Spanish wind energy manufacturer Gamesa pledged to open a new R&D center in Glasgow that could employ up to 130 engineers. Much of the activity is supported by a £70-million (US$112-million) National Renewables Infrastructure Fund recently established by the Scottish government. To put that in perspective, the U.K. government’s fund totals a mere £60 million.

Meet the Neighbors

Not all the region’s good energy is coming from energy projects. Directly next door to the defunct chip fab in Dunfermline, Amazon.com in January pledged to create a new 1-million-sq.-ft. (93,000-sq.-m.) fulfillment center that will employ 750 people, including some 100 positions moved from an existing site in Glenrothes. It’s also hiring 200 more at its existing center in Gourock. Allan Lyall, Amazon’s vice president of European operations, cited SDI’s assistance in helping the location win out over “stiff international competition,” due to the strong work force and to the company’s preference for a site near Glenrothes.

Cusick says SDI first worked with Amazon for a facility near Glasgow in 2004, then the Glenrothes project in 2005, followed by a software development center in Fife in 2006. He says the SDI team began working with Amazon about a year ago as it evaluated multiple sites in the U.K. and beyond. Assistance from SDI will total approximately £9 million, with another £1 million helping the expansion in Gourock, located near the Firth of Clyde west of Glasgow.

That facility is directly next door to an IBM complex that happens to employ 2,000. It’s a popular jobs number in Scotland. Time will tell if it rings true for Amazon’s renewable neighbors in Dunfermline as well.