One of the more bizarre political scandals in recent memory concerned a ploy by aides and associates of then-Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey to instigate traffic jams in the town of Fort Lee to punish its mayor. During the four days of “Bridgegate” in September 2013, authorities closed certain toll lanes at the George Washington Bridge leading into New York, causing I-95 traffic to spill over into Fort Lee.

Gail Toth, executive director of the New Jersey Motor Truck Association, remembers it well.

“When it started making the news,” Toth tells Site Selection, “we were all scratching our heads, because how could you tell the difference? That area is always backed up and congested.”

In the ensuing six-and-a-half years, things haven’t much improved, which is why I-95 at New Jersey State Road 4 in Fort Lee just has been identified as the nation’s worst bottleneck for trucks.

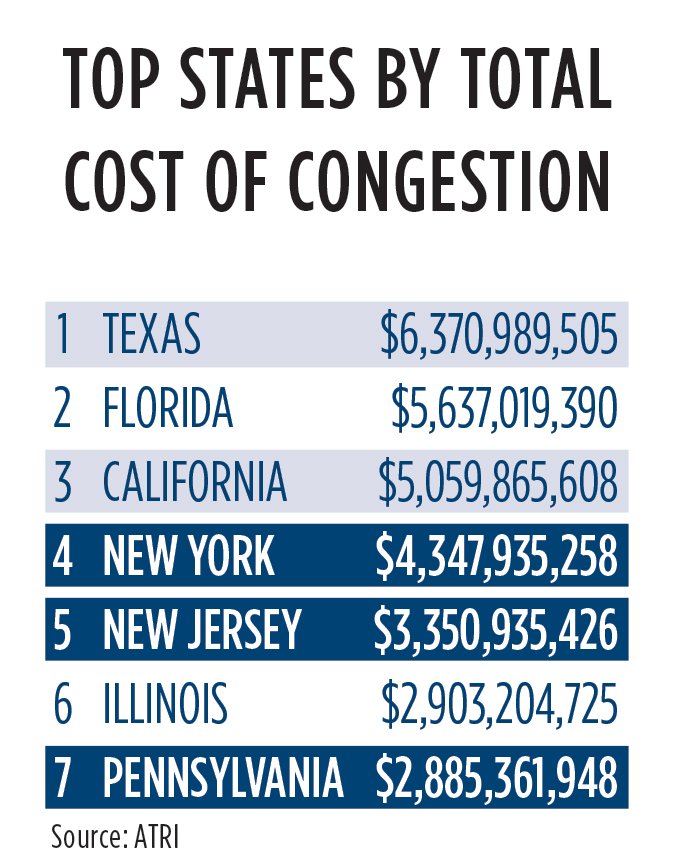

An American Transportation Research Association (ATRI) report issued in February suggests the densely populated Northeast is the nation’s most congested region for trucks. Only one state, Texas, placed more bottlenecks in ATRI’s Top 100 than did New York, which tallied seven. Pennsylvania was right behind with six. As for New Jersey, there’s always Fort Lee.

Sitting in traffic means more than just stewing and stressing. It means money. In a 2018 report on trucking industry losses due to congestion, ATRI listed New York ($4.3 billion per year), New Jersey ($3.4 billion) and Pennsylvania ($2.9 billion) among the costliest 10 states.

“Typically, we see the most egregious truck bottlenecks in locations where you have high population density, because population density requires all the things that get delivered by a truck,” says Rebecca Brewster, ATRI’s president and CEO.

Brewster and Toth agree that e-commerce, in particular next-day and same-day delivery, is making matters much, much worse.

“Distribution warehouses are growing by the gazillions in New Jersey because we’re close to the largest consumer market in the world,” Toth says. “When people complain to me about truck traffic in their area, I ask them why they approved that mega-warehouse with 100 doors. Those goods won’t be delivered by plane, train or boat. They’re coming by truck.”

The worst of Pennsylvania’s bottlenecks is at the junction of I-76, the Schuylkill Expressway, and I-676, a notorious chokepoint leading into Philadelphia from across the Delaware River. Locally known as the “Surekill Expressway,” I-76 has suffered from congestion for decades.

“Using ATRI’s bottleneck analysis, we can target infrastructure investment to those areas most affected by congestion,” says Kevin Stewart, president & CEO of the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association.

Adding new lanes is a double-edged sword, as traffic worsens during construction. Facilitating “after hours delivery,” thus allowing trucks to deliver during non-peak hours, has proved to be somewhat effective for trucks serving New York City, says Toth. Still, that’s nipping around the edges of a massive conundrum.

“I honestly don’t know what the answer is,” she laments. “We have an old infrastructure and more people using it. We haven’t built new roads and it’s difficult to expand the ones we do have, because there’s no room. They encourage people to take mass transit. Well, the problem we have in New Jersey is our mass transit is not in good condition, either. People are not going to use mass transit unless it’s dependable, clean and on time. If we could improve our mass transit capabilities, then we might be able to take some people off the road.”