Malcolm McLaren has little to do with sleek, expensive racecars or sleek, expensive musicians. But he is a rock star in his own right.

He’s not the McLaren associated with British Formula One racing and automotive design and engineering firm McLaren Group, founded by pioneering designer and engineer Bruce McLaren, who died test-driving one of his vehicles in 1970. Nor is this Malcolm McLaren that Malcolm McLaren, the late British impresario, musician and fashion icon known as a catalyst for the Sex Pistols and the British punk rock scene in the 1970s.

The founder, president and CEO of McLaren Engineering Group has a bit in common with both, however, if an engineering firm can have marquee presence: His company’s range over 41 years and a portfolio numbering more than 14,000 projects has included not only landmark infrastructure projects, but Super Bowl halftime shows, the Dancing Cranes of Sentosa in Singapore, Broadway spectacles, and engineering sets for acts including Beyoncé, the Rolling Stones, Tina Turner, U2 and Pink Floyd.

Unlike those other McLarens, he’s also still alive, a fact on his and many others’ minds when I talked to him on September 11th a few weeks ago. A piece of steel from the collapsed World Trade Center towers is part of a 9/11 memorial McLaren’s team designed in Haverstraw, Rockland County, New Jersey, where McLaren that morning had just attended a somber annual ceremony.

"I’m very proud of it," he said of the monument. "We managed to erect the piece of steel vertically so that every year at 9:06 it casts a shadow on a piece of the Pentagon we salvaged and put out in the park."

McLaren’s team had a unique perspective on 9/11 from the moment it occurred.

"We had divers in the water around the World Trade Center and the Battery when it all happened," he said, owing to the work his firm does with the ferry system in New York and NY Waterway. "They were witnesses. We were getting calls from them until the phones went out. The rescue with the ferries was very interesting — all the boats managed to tie off to Battery Park City, and they evacuated thousands of people via ferries and private vessels."

McLaren’s company was part of the huge removal and demolition effort after 9/11 too. "Teams of contractors and engineers were there to basically say, ‘You can pick up this piece without disrupting the entire pile,’ or ‘You can put the crane here.’ It was the world’s largest game of pick-up sticks, very collaborative," he says. "One person described it to me as the worst thing you could ever imagine, but the best thing you could ever see when people came together and helped each other."

His firm helped the New York-New Jersey Port Authority establish a temporary ferry landing at Pier A, enabling the system to move 25,000 to 30,000 people a day for about three weeks. The firm also has worked on aspects of the new One World Trade Center project such as its cable net wall, though confidentiality agreements prevent McLaren from talking about them. What he can say is this: "There were a lot of new considerations they didn’t have to think about when they built the first buildings."

The Meaning of Infrastructure

That ferry landing went into operation because railways, subways and bridges were shut down after the attack. It’s just one of many times — including major work helping the region recover from Hurricane Irene and Hurricane Sandy — McLaren has seen the importance of infrastructure become palpable, rather than its usual "almost subliminal" role.

"People don’t realize how important it is, but they realize it when they don’t have it," he says. It applies to site selection as well as daily commutes, he says, adopting the voice of a company leader: " ‘Let’s not go there. There are no roads, and electric costs are too high.’ You’re seeing people flee the places that are not kept up, but going to places that are."

McLaren would know where those places are. In the Big Apple region alone, his firm has designed and engineered some of the region’s most important bridges, structures, entertainment venues and public spaces, including the Long Island Railroad Post Avenue Railroad Bridge replacement (installed in 36 hours), mixed-use developments in Williamsburg, Hudson Theatre on Broadway, the Sea Glass Carousel in Battery Park, the Formula ePrix racetrack in Red Hook and the White Plains Hospital Center’s reconstruction and renovation.

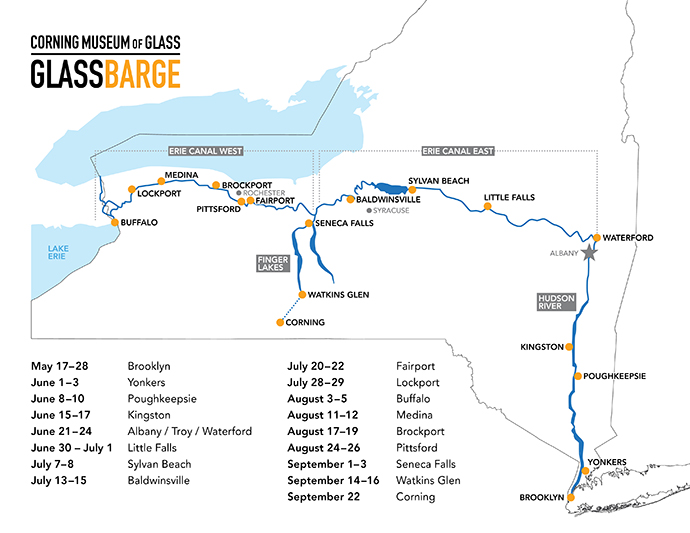

A recent history-driven project reinforces infrastructure’s linchpin role. McLaren’s firm constructed the "GlassBarge" to help Corning celebrate the 150th anniversary of its HQ move from New York City (where it originated as Brooklyn Flint Glass Company) to Corning, New York, by retracing the journey up the Hudson River and through the Erie Canal system.

"I was just up in Buffalo, looking at the Erie Canal history, and the fight about the terminus of Black Rock versus Buffalo," he says of the decision to pick the latter. "These things are real. You connect cities, and investment follows, People say, ‘That’s a place I can be and should be.’ "

GlassBarge launched from Brooklyn Bridge Park in May 2018 and took a four-month journey along the waterways that carried the company 150 years ago. Along the route, a traveling team of educators, historians and artisans invited the public onboard for history talks and free glassmaking workshops in 29 waterfront communities, with the vessel charted to return to Port of Coeymans just south of Albany in October.

Something That Works in Albany?

Sometimes a waterway is an obstacle instead of a conduit, however. That’s what has prompted yet another unique project that came about on a lark.

"One of our guys took the train from New York City to Albany," McLaren says, though the actual station is across the river from the state capital city. "He found out he was in Rensselaer, and said, ‘How do I get over there? Why is it so difficult?’ A guy in the office mentioned Macau, where we had finished a job working for Steve Wynn where we connected his casino and hotel with a gondola."

So his team called Doppelmayr, the global maker of ski lifts, cable cars and gondolas they’d worked with in Macau, to ask in very secretive language if they’d ever worked in a situation where a train station is on one side of a river and everyone wants to be on the other side.

"And he said, ‘You mean Albany, New York?’ " McLaren says with a laugh. Both cities’ mayors got on board quickly, but getting the project on the public works roll is more complicated. So McLaren’s team took the project private. "That comes with its own perils," he says, but we have some very good partnerships with the city, county and CDTA [Capital District Transit Authority]. They all see this as having a benefit, and are helping us through it. We’ve actually had some original naysayers change their mind and say, ‘Maybe it’s not such a bad idea.’ "

The project is now at the permitting stage. "The idea is this will do a lot for downtown Rensselaer and downtown Albany," says McLaren. "Our project is budgeted at $25 million, and it’s a mile of infrastructure. Where else can you get a mile of infrastructure for $25 million? That buys a quarter of a bridge or a couple feet of a road."

Making the Metro Move

McLaren announced in April it would expand to Bergen County, New Jersey, in August 2018, signing a 12-year lease on a 57,000-sq.-ft. building owned by Keystone Property Group in Woodcliff Lake that has the capacity for over 250 employees.

"This new modern facility in New Jersey will accommodate our firm’s growth, help us attract and retain talent, and position us for future success," McLaren said in the spring. "We are excited about the growth opportunities in New Jersey and the expansion of our regional footprint." That includes offices in New York City and Albany and marine services operations in Rockland County and at Liberty Landing Marina in New Jersey. McLaren’s most recent New Jersey projects include the Caven Point Marine Terminal in Jersey City, two mixed-used developments in Jersey City, the Pulaski Skyway bridge in Kearny, a recreational pier in Weehawken, automated signage at Newark Airport and wharf reconstruction at Port Newark. The firm has also worked to improve over 300 miles of coastline in the Port of New York and New Jersey.

In addition to its NY/NJ offices, the firm also maintains offices in Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania; Middletown, Connecticut; Baltimore, Maryland; Roswell, Georgia; Orlando, Florida; San Luis Obispo, California; and Oran, Algeria.

"We’ve doubled in size about every five-and-a-half to six years," he tells me, "and are now about 250 people. Growing the workforce has been good. We are now an employee-owned business, which I think is important to the culture. All employees are shareholders in the company. It’s a cultural evolution for them to understand it and make it part of their daily thinking — it’s different when you have to learn how to find your own food."

McLaren’s been finding it for a long time, so is sensitive to areas such as Bergen County that are overtly pro-business, as opposed to some jurisdictions where — like obstructions underwater — rules and regulations can slow progress to a crawl.

"We do a lot of goodwill and volunteer work, but we need to encourage business so it has the wherewithal to take care of things like that," he says. "I don’t mind paying taxes, as long as I can make enough money to pay taxes. Help us to succeed in business and to share what we can build."

He highlights the gondola project to illustrate: "We’re getting calls form other areas of the country to look at gondolas. In other states, there’s more of a "Hey, let’s just get it done" attitude," whereas New York State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQR) laws and other rules can stack up. McLaren notes that such laws enable "tremendous benefits" to the state’s environment and quality of life, "but we have to be careful balancing those benefits with progress."

Let’s Go Under and Have a Look

It’s the unique perspective McLaren brought to underwater and waterfront work that has marked his firm’s global portfolio of work, as he pioneered the discipline of professional engineer diving. Did he just dive in? In a manner of speaking, yes.

"It’s almost comical," he says. "I started my business at the ripe age of 25, a horribly stupid thing to do. I was structural engineer trying to get work doing bridge design, but of course they want to know about your experience. So I figured I must need some other line of business. I had done some scuba diving as a kid in the Virgin Islands. I thought someone must need an engineer to look at subaqueous conditions around pilings or anything submerged. So I went around selling professional engineer [P.E.] diver services, a bit higher order than a contractor. Next thing I know, I’m swimming up a live sewer outfall in the Hudson River, picking unmentionables off my head at the end of the day — I had to hose off before I could come into the house. I dove in dams built 150 years ago, under piers built in the 1920s and 1930s, and saw things that had worked and stayed in place for 50, 80 or 100 years, and things that failed in 20 years, but were hidden under water. I learned about the right and wrong way to build things in the water. I could look at problems, touch them and feel them, and think about a solution and a repair while I was down there looking at it."

Only a few individuals did what he did in the beginning. Now there’s an entire industry niche revolving around bridge and harbor inspections by P.E. divers. McLaren says most of his team’s diving work involves conveying information to a note-taker on the surface. His firm’s work has included rehabilitation of the docks at Brooklyn Navy Yard; creation of a recreational pier in Weehawken, New Jersey; and underwater inspections of historic Ellis Island. Along the way, McLaren not only invented a professional occupation, but saw an economic development opportunity literally lurking under the surface.

"I remember this vividly," he says. "I’d dive under the piers that surround Manhattan, come out and say, ‘Why is nobody here? This is valuable real estate.’ My conclusion was New York was built facing Central Park, and everything looked inward. The waterfront was where the rats and sailors lived. There used to be an active pier at the end of every street. They became dilapidated and abandoned."

Then the water got cleaned up through the Clean Water Act, the areas became more attractive and a ferry system (NY Waterway) was launched by Arthur Imperatore Sr. connecting New York to New Jersey.

"People realized this water connection, and all of these abandoned waterfront sites all of a sudden started to become valuable," McLaren says. "People wanted to live there — not on a polluted river, but on a ‘majestic view shed.’ Parks developed on the waterfront, and ferry transportation took off, linking all these waterfront sites. We’ve worked on hundreds of waterfront sites in New York Harbor as they’ve gone from fallow ground to high rises and parks and restaurants and destinations."

The firm today is also helping design terminals for New York City’s expanded ferry service.

"New York was built facing Central Park, and everything looked inward. The waterfront was where the rats and sailors lived."

He says his divers can see a lot better underwater these days because of the cleaner water, and among the things they see is more abundant sea life. But that comes with a catch.

"In the ’40s and ’50s they built things out of wood," he says, which is atmospheric but vulnerable. "Now the marine bores are back eating the wood piers, and that’s a big problem."

Oh well, all the more opportunity for sturdier redevelopment — something McLaren says could be unfolding in any number of waterfront areas.

"I think there is a lot of opportunity in a lot of cities around the country where industrial waterfront has gone to decay and can be resurrected," he says, from Great Lakes shoreline to Boston, the Bay Area and Puget Sound. "Anywhere there’s old industry. The same is true on some of the major rivers too, where there was huge industrial development because of the waterways."

Look for more from Malcolm McLaren and other New York business and community leaders in the New York state spotlight in the next issue of Site Selection magazine.