From Site Selection magazine, July 2004

ROCKY MOUNTAIN REGION

|

|

Tech Transfer Thrives

In Mountain States

ocky Mountain states have long had a leg up in But there’s also plenty of bleeding-edge research Following is a state-by-state look at some of UIRP Paces

Idaho’s Technology Effort

Doug McQueen, director of the University of Idaho Research Park (UIRP) in Post Falls, near Coeur d’Alene, says a “grow your own” economic development policy is the norm in this part of the Rockies. McQueen came to Idaho after developing Arizona State University’s Research Park. He is also a former executive director of the Association of University Research Parks.

“Our goal is to expand the presence of, and UIRP is home of the Center for Advanced Microelectronics McQueen says the technology will enable the analysis Montana Also Takes

Home-Grown Approach

Montana State University in Bozeman has plenty of efforts underway to develop startups in various technologies. These include Tech Link, a largely federally funded agency that functions as a Department of Defense (DOD) and NASA technology transfer center, and TechRanch, a recently developed business incubator. Tech Link, created in 1996, is the DOD’s only

“Our role is to find technologies that you can Swearingen cites Visual John O’Donnell considers Bozeman to be “the coolest

“We put students in the incubator, give them

Wyoming Working

to Create Firms

Wyoming has the distinction of being the only Gern says the university’s tech transfer office, In the works is a new, 25,000-sq.-ft. (2,300-sq.-m.)

“I’m becoming much more optimistic,” Gern says. One of the companies produced by the university

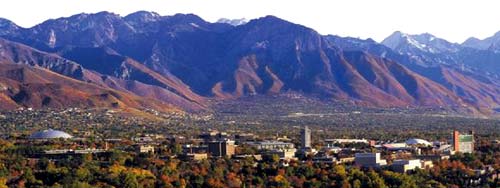

Utah Gets

Most From R&D Funds

Technology transfer is robust in Utah, with three

major universities churning out startup companies annually. In fact, the state may be the entrepreneurial epicenter in the region. Entrepreneur ranked Salt Lake City No. 5 in its annual list of Best Cities for Entrepreneurs in 2003. Tech transfer heads at the University of Utah, Dr. Jayne Carney, head of technology transfer “We have an extremely entrepreneurial faculty Dr. Ted Stanley has been director of research Stanley is also mentoring young faculty in “The university has historically been pro this The latest launch is Sentrx Kuehn, who says his new company will seek to “That will get us started and located and through Kuehn says that Utah hasn’t quite reached the “It’s not like being in Palo Alto where every Steve Kubisin, vice president, technology commercialization

About 50 companies had come out of the university “We are trying to better leverage the technology Technology in the works includes development Brigham Young University, with 30,000 students, “The amount of research we do is relatively While BYU was once known for its software design

The latest company is Procerus, Colorado Among

Research Leaders

The University of Colorado receives a half billion

dollars annually in research funds, making it the fifth largest public research university as measured by federal support. About half of that funding goes to bioscience while the remainder is spread across traditional research areas of engineering, atmospheric sciences, physics and chemistry. Startups are on the rise at the university. David “One of greatest attractions here is a high quality Thriving sectors include telecommunications,

“It accelerates the program and expands our bandwidth,” Colorado State University is in the process of “We’re assessing how we take ideas and make sure Last fall, CSU was awarded $22.1 million by the “It will make one of the largest free-standing

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

©2004 Conway Data, Inc. All rights reserved. SiteNet data is from many sources and not warranted to be accurate or current.

|