Trying to divine where manufacturing is headed is like trying to handicap a horse race. You can study all the bloodlines, workouts, race results, track conditions and personnel you want, but the past can only predict so much about what will unfold when the gates open.

The best trackside tipsters will tell you, however, that some indicators stand head and shoulders above the rest. You just have to pay attention and spot them amid a crowded field of reports, surveys and studies in order to get to the winner’s circle.

Asked to compare their intentions of hiring and technology investment in 2016, 35 percent of respondents to the MFGWatch 2016 survey, released in June by sourcing professional and contract manufacturing marketplace MFG.com, said they planned to invest in new technology and hire more. Thirty-two percent said they will be investing in new technology but not hiring; 25 percent said they are neither hiring nor investing in new technology; and a mere 8 percent said they are hiring but not investing in new technology.

But even as tech rules, the importance of humans persists: Both buyers and suppliers of custom manufactured parts indicated that access to a competent workforce would be a major challenge facing the manufacturing industry going forward, with 25 percent of respondents calling it the biggest challenge facing manufacturing this year.

Where advanced manufacturing is going depends in part on where manufacturing is advancing. According to the MFGWatch survey, US sourcing professionals chose to source their parts predominantly in the United States (80 percent), China (35 percent), and Canada (20 percent).

Turn to the Index

Where will those who choose to grow advanced manufacturing investment in the US find the best critical mass of infrastructure, talent and support?

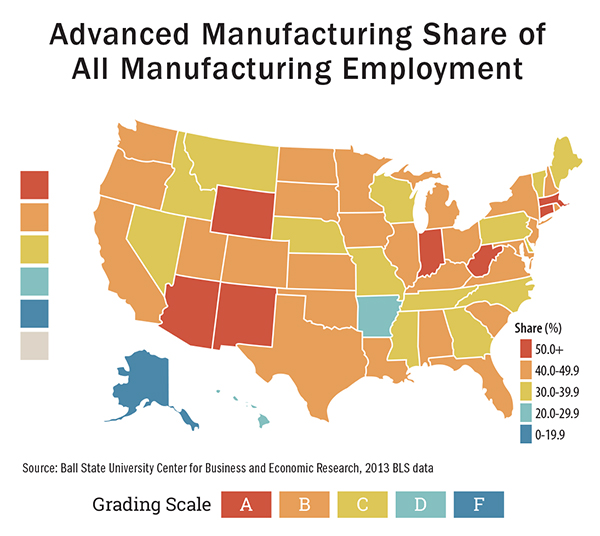

Ball State University’s Center for Business and Economic Research (CBER) has some ideas in its 2016 Advanced Manufacturing in the United States report, prepared for Conexus Indiana, and state’s advanced manufacturing initiative.

CBER Director Michael Hicks uses the Brookings Institution’s definition of advanced manufacturing as an industry sector with high levels of STEM-related occupations and R&D investment in order to evaluate each state’s advanced manufacturing employment as a share of total manufacturing employment in 2013, across 35 industry sectors. The sectors were selected based on the post-recession rebound, impact to US economic activity (value added and GDP), employment share in occupations with large numbers of engineers, and increased contributions to private sector R&D, patents, and to exports.

“These sectors contribute significantly to employment in most states, and are especially important to Midwestern states, comprising a significant share of overall manufacturing,” said the CBER report.

Indiana’s share was 52.6 percent, which was the third highest after New Mexico (54.5 percent) and Wyoming (52.9 percent). “Because Indiana has the largest manufacturing sector in the United States, it is also true that Indiana has the largest state share of advanced manufacturing in the nation,” said the report.

Hicks and his team also showed a positive correlation between employment in the swath of industries and changes in the share the adult population with associate’s degrees or higher. Data show that, nationally, STEM and white-collar jobs are growing in the advanced manufacturing sector, while blue-collar occupations have declined.

“These data underscore the importance of talent development efforts with a focus on educational attainment,” Hicks said with the report’s release. “In the long run, a well-educated and ready workforce matters more than any other single factor in the health of advanced manufacturing firms.”

Strengthening the Sector

Other things matter too, however: regulation of licensing and patents, intellectual property protection and public investment in R&D. In a June 2015 report, Hicks and Ball State CBER senior research associate and project manager Srikant Devaraj disputed with evidence the notion that manufacturing is in decline in the US, though they did not dispute that productivity hurt job growth. The Myth and Reality of Manufacturing in America reported that 88 percent of job changes in manufacturing were due to automation, with only 13 percent due to trade imbalances. And they concluded by pointing to some possible solutions for keeping manufacturing strong:

“Exchange rates clearly play a part of the role of manufacturing import substitution and employment displacement,” they wrote. “Any non-market factor which influences dollar valuation should be diligently opposed by international trade agencies and agreements.

U.S. national corporate income tax rates are the highest of the OECD nations, and clearly impose a disincentive for transnational corporate location in the U.S. The government should consider lowering barriers to headquarter[s] and manufacturing facility location through a reduction of federal corporate tax rates.

“Sustainable manufacturing employment growth requires high levels of human capital,” they continued. “The nation and individual states should actively support education reforms at the secondary and tertiary level that prepare students for employment opportunities in manufacturing, which will be large due to job turnover among the baby boom share of the manufacturing labor force. Human capital interventions should also begin at the pre-K level, focusing on skills that enable acquisition of the mathematical and cognitive skills required of the modern manufacturing workforce.”