Micropolitan statistical areas, or “micros,” are odd animals. A micropolitan is a core-based statistical area, in this case a county, whose name derives from its core city of 10,000 to 50,000 residents. William Fruth, who evaluates micropolitan economies as president of the Florida-based consulting group, POLICOM, says the tortured configuration is a matter of bookkeeping.

“Ninety-five percent of all economic data is generated by the counties, with very little at the municipal level,” says Fruth. “But the micros are [named for] the cities.”

Micropolitan oddities include Pahrump, Nevada, whose area consumes nearly one-fifth of the state. That’s because Pahrump, population 36,441, anchors Nye County, which covers some 20,000 sq. miles (52,000 sq. km.).

To further muddy the waters, a given micropolitan can cover adjacent counties and even bleed into adjacent states, should the U.S. Census Bureau establish significant “economic integration” tying those outlying areas back to the core. Also, some micros are named for multiple cities (see Eureka-Arcata-Fortuna, California), because more than one city within a single county might qualify as a core.

“It gets confusing,” acknowledges Fruth.

Still, as modestly sized “contained economies” focused around a single population center, America’s 542 micropolitans, as identified by the White House Office of Management and Budget, do provide a lens on small-town America. Cities identified as micropolitans tend to be older, less diverse and more blue-collar than the nation as a whole, with higher shares of workers employed in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, forestry, fishing and hunting. In 2000, people living in micros accounted for 9.2% of the U.S. population. By 2017, the micro population had shrunk to 8.4%.

New Players Arrive, But Top Performers Stick Around

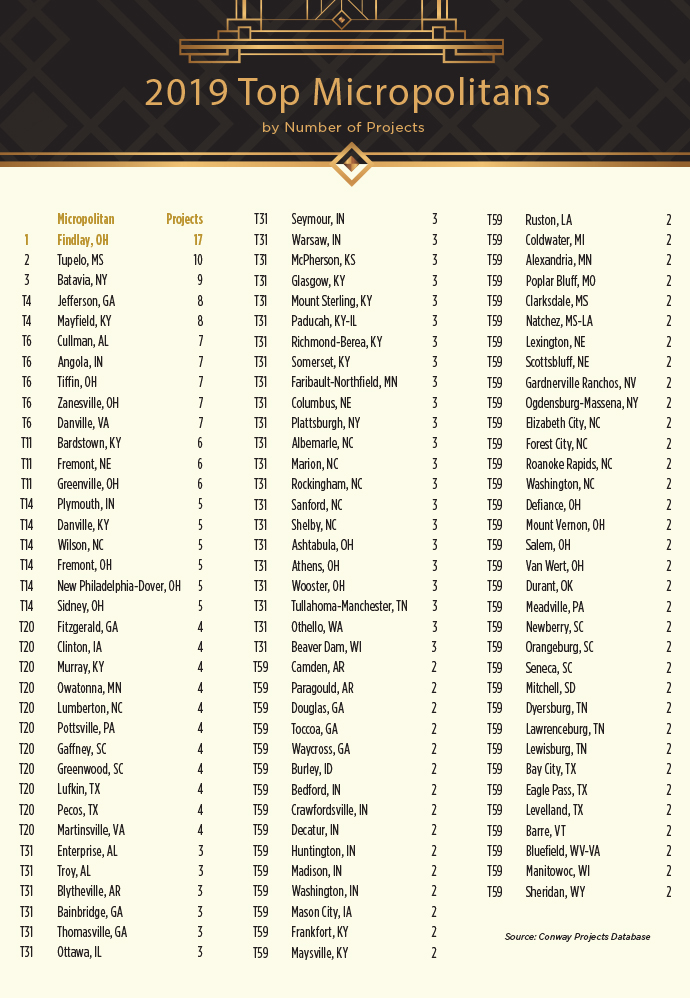

In comparison to the previous two years, Site Selection’s Top 100 Micropolitans for 2019 cover qualifying investments in an unusually wide range of states. Micros in 30 states are represented, up from 22 states in 2018 and 23 in 2017. Newcomers in 2019 include towns in Nevada, Washington State, West Virginia, Minnesota, Iowa, Idaho, Oklahoma and Vermont; With investments totaling $150 million from sock maker Cabot Hosiery and distiller Caledonia Spirits, the town of Barre, Vermont, is the first Vermont micro ever to crack our Top 100.

But consistency rules the day, beginning with Findlay, Ohio. A manufacturing-heavy city of 41,000 people about an hour south of Toledo, Findlay is Site Selection’s Top Micropolitan for the sixth consecutive year, an unprecedented run of success. Of Findlay’s 17 qualifying projects totaling $181 million, 16 represented expansions of existing businesses. Tops among those is Whirlpool’s $65 million investment in what already is the world’s largest dishwasher plant, soon to start production of a newly designed unit that includes three racks, the first of its kind.

Tupelo, Mississippi, a Top 10 stalwart, climbs this year to second place in our micropolitan rankings, a feat it previously accomplished in 2008. Like Findlay and most other successful micros, Tupelo leans heavily on growth by its established businesses, including San Diego-based General Atomics, the nation’s largest privately-owned defense contractor.

“Taking the risk out of expansion is what we’re all about,” says David Rumbarger, president and CEO of Tupelo’s Community Development Foundation.

Taking the road less traveled, Batavia, New York, registered seven new investments and two expansions on the way to its second consecutive third-place showing. Jefferson, Georgia, makes the biggest jump this year, vaulting from a tie for 62nd in 2018 into a tie for fourth place with Mayfield, Kentucky. The rest of the Top 10 includes Angola, Indiana; Cullman, Alabama; Tiffin, Ohio; Danville, Virginia and Zanesville, Ohio.

“TAKING THE RISK OUT OF EXPANSION IS WHAT WE’RE ALL ABOUT.”

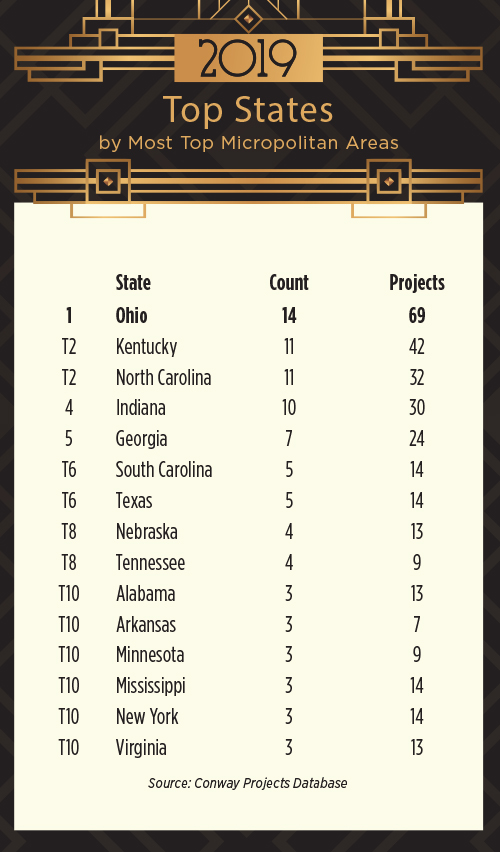

As in past years, Ohio is home to biggest number of towns in our Top 100 (14), followed by Kentucky and North Carolina (11), Indiana (10), and Georgia (7).

How do these Top Micropolitans earn such consistent success? Here’s what three of them are telling us.

To its great fortune, Findlay begins with an enviable set of built-in advantages. The town straddles Interstate 75 two hours south of Detroit, which has helped Findlay nurture a formidable automotive industry. The University of Findlay is a top-notch private academic institution that’s deeply involved in economic development. Marathon Petroleum and Cooper Tires, both of which have their headquarters in Findlay, are prestigious, repeat investors, as is the aforementioned Whirlpool, which employs more than 2,300 workers.

But what truly defines Findlay is its engaged business community and an aggressive, opportunistic approach to economic development. (To learn about one of Findlay’s innovative business retention programs, see “Eyes Wide Open” in Site Selection’s November 2019 issue.)

A crucial part of “the Findlay Formula” is the ability to recognize, seize and develop opportunities more swiftly and boldly than others might. No better example exists than the Findlay community’s longtime embrace of manufacturing companies based in Japan.

The decades-long relationship dates to a serendipitous, 1986 trade mission to the Japanese city Nagoya by Findlay’s then-mayor Keith Romick, its economic development director and the president of the University of Findlay. Over dinner at a Chinese restaurant, Romick hit it off famously with Japanese businessman Kohei Suzuki, who in 1989 would open G.S.W. Manufacturing, Findlay’s first fully owned Japanese business.

Other Japanese manufacturers followed the lead of G.S.W., and over the ensuing decades, have invested billions of dollars in Findlay. As just one example, 30 years since Sanoh America planted its flag there, the company still is investing in Findlay; its $6 million North American headquarters expansion, with 65 new hires, represents one of the Findlay micro’s 17 qualifying projects for 2019.

Likewise, Nissin Brake, which took root in Findlay in 1988, made a 2019 investment of $8 million that created 44 jobs. Nissin’s investments over the past three decades reach into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

“This is a long-term play that you have to invest in, and that’s what we’ve done that is different from almost any other community,” says Tim Mayle, director of Findlay-Hancock County Economic Development. “This is something we have nurtured over many years through multiple mayors and multiple economic development directors. We have consistently said we are going to invest in Japan and vice versa. Some people will go on a trade mission one time and be done. You cannot do that.”

Japan native Hiroaki “Hiro” Kawamura, director of Modern Language at the University of Findlay, also carries a business card that identifies him as Mayle’s special assistant. In that capacity, he serves as something of an ombudsman for all things Japan. Visa problem? Call Hiro.

He’s likely to get a call, as well, if a Japanese student in Findlay City Schools is experiencing difficulties, or if a Japanese patient is admitted to Findlay’s Blanchard Valley Hospital. Perhaps more than anything, Kawamura keeps his ears to the ground and serves as a conduit between the Japanese business community and Findlay’s leadership.

“My work is basically behind the scenes,” Kawamura says. “This is a partnership where both sides work together.”

A Deepening Friendship

Friends of Findlay is an ad hoc group consisting of the presidents of 13 Japanese companies in northern Ohio, some an hour or more away. Most of the “Friends” live in Findlay, though, largely because of steps the town has taken to welcome the Japanese community — chiefly the introduction of English as a Second Language instructors into public schools. In addition, dozens of Japanese students each Saturday take a bus provided by Findlay City Schools to and from daylong Japanese classes in Toledo. Findlay’s Blanchard Valley Health System makes conscious efforts to respect cultural differences when treating Japanese patients.

“We’ve made it extremely convenient for our Japanese expatriates, because the culture of America versus the culture of Japan is very different, and we’ve done our best to accommodate theirs,” says Mayle.

“IT’S NOT BY LUCK THAT WE HAVE THESE JAPANESE COMPANIES.”

At the same time, the Japanese community has left an indelible mark on Findlay, where Japanese cherry trees line the popular Riverside Park and Findlay City Hall. Bilateral ties with Japan include sister city arrangements and student exchanges. This year, when Findlay High School introduced Japanese language classes, more than 60 students signed up.

But there’s no greater symbol of mutual respect and affinity than Japan West, the downtown Japanese restaurant established by Kohei Suzuki to cater to Japanese families and to extend Japanese culture. Suzuki, who was affectionately known in Findlay simply as “the Chairman,” decreed before his death in 2014 that Japan West would never close its doors. It’s become a favorite for birthdays, anniversaries and other special occasions and a cultural bridge between Americans and Japanese.

This lucrative international partnership represents another opportunity identified and seized upon by Findlay’s economic leadership.

“From this one meeting in Japan in the late ’80s,” says Mayle, “we now have several thousand people employed. We have our youth experiencing cultural opportunities globally. You cannot go to a park in Findlay without seeing cherry trees, symbolizing the relationship between Findlay and Japan. It’s not by luck that we have these Japanese companies.”

Known worldwide as the birthplace of Elvis, Tupelo flies under the radar when it comes to economic development. Maybe it shouldn’t. The town of some 38,000 people is the commercial and industrial hub of North Mississippi.

Funny thing, too. Tupelo shares something important with Findlay.

“Tupelo does not miss the chance for opportunity,” says David Rumbarger of Tupelo’s Community Development Foundation. “Our business leaders are well studied. They’re skeptical, as well, but in the end, action prevails. They’d rather implement a good plan than wait for the perfect plan. And because of that, there’s a lot of activity and movement here.”

For a town of its size, Tupelo was early to the incubator game, having launched its Renasant Center for IDEAS all the way back in 2004. Sponsored by Renasant Bank and located on Tupelo’s Main Street, the 36,000-sq.-ft. (3450-sq.-m.) facility has graduated some 30 companies that have created more than 800 jobs over its 15-year history.

Hyperion Technology, whose $1 million expansion created 25 jobs in 2019, is one of those companies. Hyperion launched from the Center in 2009, and now provides custom electronic systems to the U.S. military and commercial customers. Its move into a space four times the size of its previous facility represents one of Tupelo’s 10 qualifying projects for 2019.

Another qualifying investment came from furniture maker Homestretch Holdings, itself a graduate of the Renasant Center. Formed in 2010, the company employs more than 500 people and hired 71 workers in 2019.

“We’ve got both service centers and manufacturers there in the Center, and what it does is it gives them a chance to fail, and obviously, a chance to succeed,” says Rumbarger. “It proves out their concept and helps them build their marketplace. It gives them a Main Street address, conference rooms and shared services. It allows them to get their businesses up and running, and in the case of Hyperion and Homestretch Holdings, they’ve done great things.”

High-Level Stuff

Long known as a center of furniture manufacturing, Tupelo registered qualifying investments in 2019 totaling more than $30 million from Homestretch, Leggett and Platt, Sofa Kraze, local institution H.M. Richards and Ashley Furniture Industries.

Tupelo’s biggest 2019 investment came from Cooper Tire and Rubber Company, an anchor of the Lee County economy since 1984. Cooper updated its automation process to the tune of $52.5 million and made 35 new hires. Its hometown? Findlay, Ohio.

Less well-known than Cooper but of equal importance to the Tupelo economy, San Diego-based defense contractor General Atomics put $50 million into the latest of its many physical expansions since arriving in 2005. Beginning then with a modest 30,000 sq. ft. (2,787 sq. m.), the private company’s built-out footprint has grown to more than 20 times that. Peter Rinaldi, vice president for manufacturing and operations, says the company’s combined investments total “north of $500 million. I’ve done an expansion almost every year.”

“THERE’S A LOT OF EXPERTISE AND ENGINEERING IN WHAT WE DO.”

General Atomics developed an electromagnetic “launch and capture” system to facilitate takeoffs and landings from the decks of the new Gerald R. Ford class of aircraft carriers. Parts manufactured at the Tupelo plant, says Rinaldi, can individually cost more than half a million dollars.

“Ours is a highly engineered manufacturing environment,” he says. “It’s not somebody bolting on a bumper. There’s a lot of expertise and engineering in what we do. We’re going up against the big guys, the ones that are publicly traded like Northrop Grumman, General Dynamics, Boeing and Lockheed Martin.”

Rinaldi says Tupelo “checked all the boxes” when General Atomics faced the need for a rapid expansion 15 years ago.

“Mississippi had a large workforce that was available, and workforce training grants,” Rinaldi says. “The land was available, and since we require multiple megawatts of power to test, we had to have power availability. The TVA supported the effort of Mississippi and Lee County to get us the power and the infrastructure we needed. Mississippi fared well in all these things.

“In terms of workforce,” Rinaldi says, “a lot of folks came out of the furniture industry and had never seen an electric motor in their life. But it’s been a pleasant surprise. The ability and desire to learn and to continue to learn has been top notch. You have to have a willingness to keep learning, and the workforce we have hired is excited about learning. This has allowed us to be successful. We could not do it without the people we have here.”

Scarcely a decade ago, leaders of Kentucky’s signature bourbon and distilled spirits industry poured whiskey on the steps of the state Capitol to protest the latest tax hike on spirits. In February 2019, they poured bourbon inside the Capitol to toast the industry’s epic turnaround. Bourbon barons joined elected officials and key business executives to unveil a study showing that bourbon provides twice the jobs, payroll, capital investment and tax revenue as it did just 10 years before.

Perhaps no other town in Kentucky has reaped the rewards of the bourbon boom as much as Bardstown, No. 11 on our list of Top Micropolitans, a town that first landed on our radar in 2015. Sitting as it does at the southern tip of Kentucky’s “Amber Triangle,” whose other points include Louisville and Lexington, the town of 13,000 residents tallied bourbon-related investments of $50 million in 2019.

“We have always been the center of Kentucky bourbon,” says Kim Huston, president of the Nelson County Economic Development Agency. “We’ve always had distilleries and operations here, even when bourbon wasn’t on the front burner of people’s minds. So, when this bourbon boom started, not only did our existing facilities start cranking it up and building more facilities as quickly as they could, but new distilleries got into the game. We have located three or four distilleries here in the last three years.”

One of the newcomers to Bardstown’s bourbon business is a 56-year old entrepreneur whose name is synonymous with the Great American Spirit. J.W. “Wally” Dant is the great-great grandson of pioneering distiller John Washington Dant, who, in 1836, created a poor man’s whiskey still from a hollowed-out poplar log. At the time, he was only 16. By the 1950s, says Wally Dant, “he’d become a big producer of bourbon and quite well known for it.”

John Washington Dant had seven sons, all of whom immersed themselves in distilling.

“His sons came into the business and then produced on their own,” says Dant. “After that, my family was involved in bourbon production all the way through the early 1970s when my grandfather retired. Outside of the Beams, no one can say that their family has been in the business this long.”

Having found success in the healthcare industry, Wally Dant is returning to the family tradition. If things go as planned, he’ll be producing bourbon and rye next year at the site of the former Gethsemane Distillery, once run by his great grandfather William Washington Dant. The newly-named Log Still Distillery, named for J.W.’s original still, will include a restaurant, visitors center, and a whole lot of history.

“We’ll be using similar processes to those that were used from the early 1900s,” Dant says. “We’re trying to replicate as much as we possibly can. We’ll be using limestone water from the same pond they used, fed by the same creeks and springs. Of course, we’ll be using modern equipment, but we’re doing as much as we possibly can to authenticate what my family has been doing for generations. When it comes to the Dant family and our history, we’re going to showcase that.”

“PEOPLE REALLY WANT TO SEE YOU BE SUCCESSFUL HERE.”

Dant will house his whiskey-making equipment where his great-grandfather did, in a Quonset hut that’s undergoing a full renovation. An old barreling house will serve as a tasting room. The distillery’s iconic water tower has been restored for use already.

Dant expects to invest some $12 million and to create up to 20 full-time jobs. Log Still Distillery qualified for up $500,000 in tax incentives through the Kentucky Business Investment Program and was approved for tax incentives totaling as much as $100,000 through the Kentucky Enterprise Initiative Act.

“I knew we would be welcomed back,” says Dant. “But what I’ve found is that people really want to see you be successful here. I just tip my hat to everybody in the state and at the local level who’s been so supportive of our efforts. It’s a blessing to be a part of that and to contribute to what’s going on here in the bourbon industry. It’s a great time to be in this business.”

Nice Town, Nice People

Despite the outsized influence of the bourbon industry, the Bardstown economy is no one-trick pony. As just one sign of the community’s economic health and diversity, unemployment in Nelson County plummeted to 5.9% in 2019 from 9.1% the year earlier.

“Bardstown,” says Huston, “is very heavy in industrial development. We have 62 manufacturing facilities. For a community of around 14,000 people, that’s a lot.”

In March 2019, automotive supplier Itsuwa announced plans to locate its second U.S. plant in Bardstown, a $5.2 million investment expected to create 43 new jobs. Itsuwa is the eighth Japanese manufacturer to set up shop in Nelson County.

Tokyo-based Takigawa, a maker of pet food packaging, launched production in late 2019 at its new Bardstown production facility.

“Kentucky and Nelson County were very aggressive with the incentives they offered us,” says Takigawa President Kensuke Yamamura. “After several meetings with the governor’s office and with Kim Huston and her people, we concluded that we could believe in their ongoing support.”

For its first location in the U.S., Takigawa cast a wide net that included 150 potential locations. In the end, Kentucky’s central location proved vital to the company’s decision.

“We have existing customers in the USA, and Kentucky’s location makes it very easy for us to reach them,” Yamamura says. “We can reach all of them within a day’s drive. Bardstown is a great place for us, too. It’s a nice, small town with nice people. We are very happy here.”