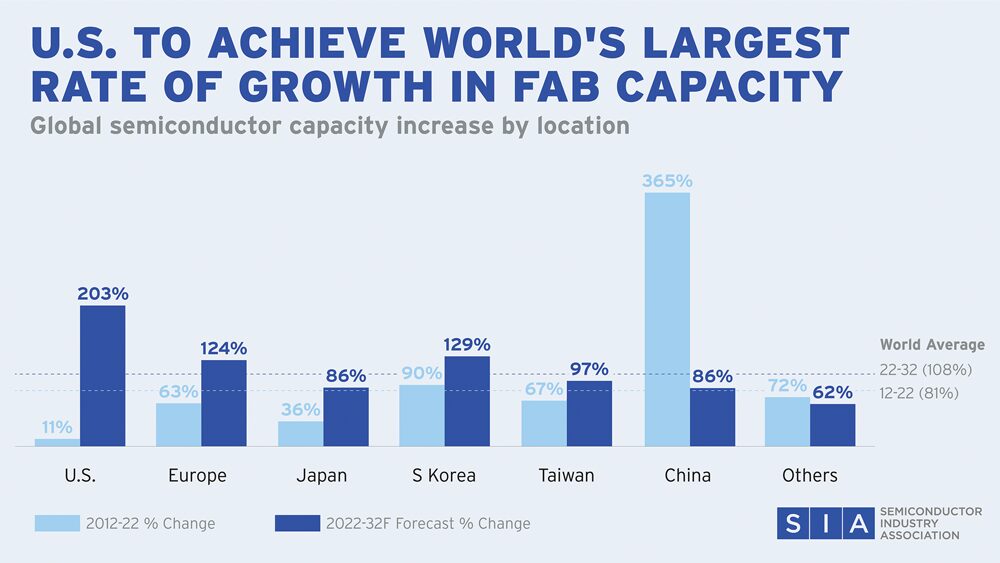

The U.S. will triple its semiconductor manufacturing capacity from 2022, when the CHIPS and Science Act went into effect, to 2032, according to a report from the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), in partnership with the Boston Consulting Group. The projected 203% growth is the largest projected percent increase in the world over that time. The study, “Emerging Resilience in the Semiconductor Supply Chain,” also says the U.S. will grow its share of advanced logic (below 10nm) manufacturing to 28% of global capacity by 2032, up from 0% in 2022, according to an SIA release.

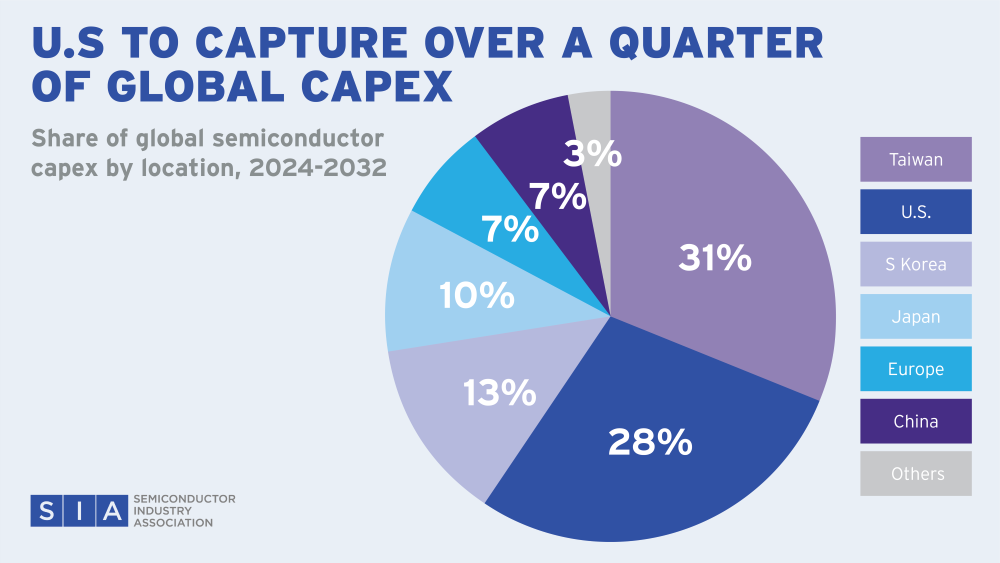

Additionally, America is projected to capture over one-quarter (28%) of total global capital expenditures (capex) from 2024-2032, ranking second only to Taiwan (31%). In the absence of the CHIPS Act, the U.S. would have captured only 9% of global capex by 2032, according to the report.

The report also analyzes the efforts underway in other countries to incentivize chip production and innovation and the criticality of ensuring chip companies have open access to global customers and suppliers, among other topics.

“Effective policies, such as the CHIPS and Science Act, are spurring more investments in the U.S. semiconductor industry,” said Rich Templeton, chairman of the board at Texas Instruments and SIA board chair, in the release. “These investments will help America grow its share of global semiconductor production and innovation, furthering economic growth and technological competitiveness. Continued and expanded government-industry collaboration will help ensure we build on this momentum and continue our next steps forward.”

Other key report findings per SIA:

- America’s world-leading 203% projected increase in fab capacity from 2022 to 2032 stands in stark contrast to its modest 11% increase from the previous decade (2012-2022), which ranked last among all major chip-producing regions, according to the SIA/BCG report.

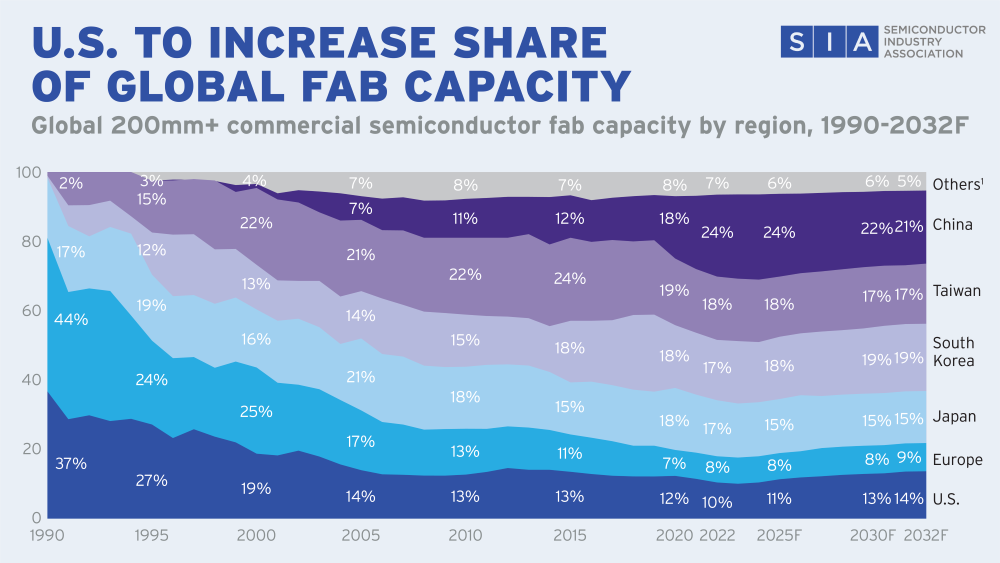

- The U.S. share of the world’s chip manufacturing capacity will increase from 10% in 2022 — when the CHIPS and Science Act was enacted — to 14% by 2032, marking the first time in decades the U.S. has grown its domestic chip manufacturing footprint relative to the rest of the world. In the absence of CHIPS enactment, the U.S. share would have slipped further to 8% by 2032, according to the report.

- The U.S. continues to lead the world in its overall contribution to the global value chain, with strong leadership positions in high value-added areas of semiconductor technology, including chip design, electronic design automation (EDA), and semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

See charts throughout this article for SIA visuals.

NOTES FROM THE FIELD:

What to Know About Siting a Semiconductor Plant

Robert Hess, Vice Chairman, Global Strategy, and Vice Chairman, Global Corporate Services, Newmark

Gregg Wassmansdorf, Senior Managing Director, Global Corporate Services, Canada, Newmark

Landing a semiconductor fab facility is transformational for any community. For better or worse, depending on one’s perspective, things will never be the same. The ramifications can be overwhelming. But effective leadership and communication with stakeholders can turn local trepidation into optimism. In December, Site Selection spoke with two veteran site selectors with years of experience working with companies and communities on the sometimes-thorny process of siting and establishing megaprojects, including chip plants.

Following is a Q&A with Newmark Vice Chairman, Global Strategy, and Vice Chairman, Global Corporate Services Robert Hess and Senior Managing Director, Global Corporate Services and Senior Managing Director, Canada Gregg Wassmansdorf.

What is meant by “placemaking” in the context of new chip fab facilities being built?

Robert Hess: I met recently with a large South Korean client that we have done many battery plant and semiconductor studies for. We met about the site selection projects we’re working on, but we also met with two other divisions that were focused on placemaking around those assets. They were talking about multifamily housing, housing for their workers, live-work-play environments — everything we’ve seen being important post-COVID is on their minds also, making these large projects successful. I’ve been thinking about this for years and years looking at sites, but how are the developers thinking about this? It’s about communities and economic development coming together. This has been a big thing for some time, but it will be even bigger going forward.

Photo by SweetBunFactory: Getty Images

“If the housing, the daycare, the public transportation, if the public infrastructure isn’t there, what economic development ends up selling becomes a fiction, so divorced from what the community can support that the projects you attract end up struggling or even failing.”

— Gregg Wassmansdorf, Senior Managing Director, Newmark

Gregg Wassmansdorf: In some locations, community development and economic development have gone in different directions with separate staffs, separate budgets and separate agendas. What we have been emphasizing as a practice to communities and regions is you have to bring community development and economic development back together. If the housing, the daycare, the public transportation, if the public infrastructure isn’t there, what economic development ends up selling becomes a fiction, so divorced from what the community can support that the projects you attract end up struggling or even failing. You have to bring the two back together. This is especially true of the mega projects, these fabs where without a concerted, focused effort on these placemaking initiatives you run the risk of bending or breaking the community in which you land. It becomes an all-hands-on-deck effort, and we sometimes see it formalized in an incentives package. For example, in New York you won’t get Green CHIPS [Community Investment Fund] money if you are not committed to doing some of these things. In other places it might not be documented in that way, but it’s understood that we must get everybody moving in the same direction to raise the capacity of the whole community to support what is about to come.

With so much chip production coming back to the U.S., is NIMBY resistance an issue as companies look for suitable sites?

Gregg Wassmansdorf: The short answer is yes. These projects are so large it’s hard to imagine what these projects will mean when they land in a community. There is concern, fear and uncertainty. There is excitement as well, a whole blend of emotions that percolate to the surface and everyone is motivated by different concerns, such as loss of agricultural land or congestion on the roads or the kinds of jobs it’s creating in these hard times. It takes a lot of education by state, regional and local leaders and workforce development agencies. Like I said, it’s all hands on deck. It takes a lot of public education to bring communities along the path of accepting economic growth generally and I think that it is magnified when it’s a megaproject. These things are inflection points that change the future of a community and a region. So it requires discussion about what this really means.

“We want more sites, and we want more ready sites, more qualified sites. That’s our mantra. But I’m wondering if there isn’t some decent product out there that just needs to be reimagined, repositioned and repurposed.”

— Robert Hess, Vice Chairman Global Strategy, Newmark

Robert Hess: It helps to look at it by asset type. A hyperscale data center is not a gigafactory, a cell plant is not a fab and it’s not advanced manufacturing in some other industry. They all have a “NIMBYism” meter. Economic impact studies by third parties have shown that the multiplier effect for hyperscale data centers is just short of what a semiconductor is. With fabs there is generally less NIMBYism. It also depends on whether the area is targeting the industry and whether they are preparing for it. Transparency is important and it helps to have coalitions up front so that things will go smoothly when you get to that city council meeting.

Gregg Wassmansdorf: Depending on where you look around the country, depending on the sourcing strategy of the fab and their localization strategy, you can see in places around the country where there might be only 10 or 15 or 20 suppliers located near the fab and in other areas there are 75 or 90 or 100 companies that are all oriented toward the fab. That large clustering effect tends to be more common. That raises the question for a lot of communities, ‘If I’m on the west side of town and the fab landed on the east side of town actually in a different city within our metro area, how do we get some of the action?’ We know the fab has landed but we don’t know who the suppliers are or where they will locate. Part of that education process is helping communities understand that after the fab you still have requirements for heavy, medium and light industrial lab facilities, light industrial and office throughout the entire value chain. There are opportunities for communities within a metro to potentially get a piece of the action whether that’s small, medium or large, with different asset types and different workforce requirements.

What’s your take on the current supply of megasites necessary for fab projects?

Robert Hess: We want more sites, and we want more ready sites, more qualified sites. That’s our mantra. But I’m wondering if there isn’t some decent product out there that just needs to be reimagined, repositioned and repurposed. As site selectors ourselves, sometimes we find diamonds in the rough like a brownfield site that is almost clean. Can we accelerate this and repurpose it? We have clients that want us to look at greenfield and brownfield sites and potentially even urban versus just finding sites on the edge of the city. They want to know if we looked at everything.

Gregg Wassmansdorf: There are very few sites out there that are large — 500 acres or more — that you could call ready. Of the 2,000 or so sites that Newmark has looked at in the last five years or so in our project work, about 8% are 1,000 acres or more at various stages of readiness. It does take some imagination sometimes to perceive what is it now and, on the timeline of getting all the infrastructure and the site ready, whether this site in the future has the capability and capacity to support what we’re doing. Places like Clay, New York, that won the Micron project — that’s another site that we identified and vetted and then put forward and supported the state of New York with. They had to first lose TSMC to Arizona and then lose Intel to Ohio. They had spent so much time and effort getting ready and making investments that when Micron came along and asked them all their tough questions their answer to almost every question was, ‘Next slide. We have the answer for you. We’ll show you the plan. We’ve done our homework, and we know what it takes.’ But that’s years of effort, years of getting to a position of readiness. It doesn’t mean the pipes are in the ground, but it means that conceptualization and design engineering work has been done so they can say with confidence they can actually deliver what they say they can deliver.