Let the sunshine in, and you very well might see something grow.

Sunshine Week is a national initiative to promote a dialogue about the importance of open government and freedom of information. Launched by news editors and journalists, this non-partisan, non-profit initiative is celebrated in mid-March each year.

Sunshine Week just ended, but that’s no reason to stop the light from shining. It’s easy to turn up your nose at information you’re convinced is tainted with ideological fingerprints different from yours. But that’s no reason to ignore the core facts uncovered by such research, however obscured it may be by the rhetoric crafted to pitch that information to the battle-weary public.

Exhibit A: D.C.-based non-profit Good Jobs First (GJF), which seeks to shed light on all incentives, usually with the aim of proving them wasteful, even if some of the jobs created are indeed “good jobs” in many people’s eyes.

Good Jobs First has recently ramped up its Web resources in the form of a “Subsidy Tracker” database and separate but related reports on clawbacks and on job quality analysis of economic development subsidy programs.

While the organization generally rants against corporations in general and engages in the now rote demonization of Wal-Mart in particular, it’s also doing a great public service by trying to assemble all the data for our viewing pleasure. Thus you can sort through the 5,209 subsidies tracked in 2011, some of which might help us here at Site Selection evaluate those projects which in our view merit recognition as the year’s Top Deals in Economic Development, to be unveiled in our May issue. Thanks GJF!

In a December 2010 report, GJF found Illinois, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Ohio had the best economic development disclosure. In addition, Missouri, N.C., Ohio and Wisconsin were the only states providing recipient reporting for all key programs examined by GJF. Meanwhile, 13 states and D.C. had no disclosure at all.

Ohio and North Carolina are perennial contenders for Site Selection’s Governor’s Cup and other economic development rankings, proving that disclosure may not be the project threat it’s often made out to be.

“With states being forced to make painful budget decisions, taxpayers expect economic development spending to be fair and transparent,” said Good Jobs First Executive Director Greg LeRoy then. “Claims that sunshine would hurt a state’s business climate have been discredited, trumped by people’s rising expectations about government information being online.”

Since that report, Oregon and Massachusetts are among the states that have advanced toward more incentives transparency.

Among the GJF’s clawback report’s key findings:

- Ninety percent (215 of 238) of the programs require companies receiving subsidies to report to state government agencies on job creation or other outcomes. Yetin 67 (or 31 percent) of those 215 programs, an agency does not independently verify the reported data. The District of Columbia and South Carolina have no performance verification in any of their five major programs examined.

- The states with the highest program scores are: Vermont (79), North Carolina (76), Nevada (74) and Maryland (70); those with the lowest averages are: the District of Columbia (4), Alaska (19) and North Dakota (30).

Greg LeRoy and GJF Research Director Phil Mattera said keeping up with online disclosure is a daily and sometimes tricky process.

“Florida is a strange case,” said Mattera. “There was some online disclosure, but when Governor [Rick] Scott took over, that website was removed. Recently the state released a big spreadsheet of deals going back to 1995, but the state did not post that on the Web. One newspaper did that, and we incorporated that into our Subsidy Tracker database.”

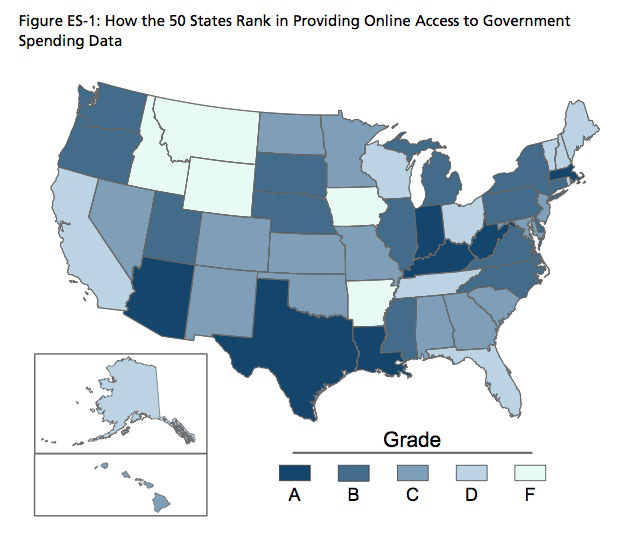

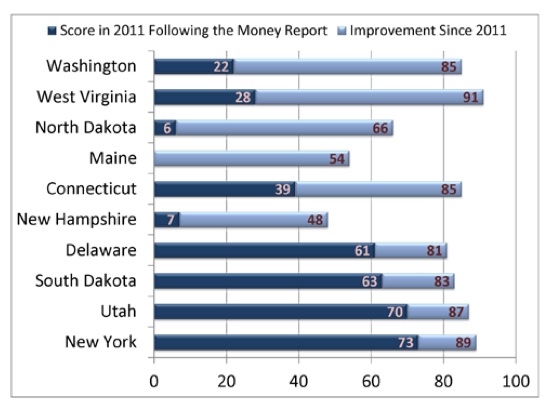

Another recent report is “Following the Money 2012: How the States Rank on Providing Online Access to Government Spending Data,” the U.S. PIRG Education Fund’s third annual ranking of states’ progress toward “Transparency 2.0,” which it defines as “a new standard of comprehensive, one-stop, one-click budget accountability and accessibility.” Texas led the way, followed by Kentucky, Indiana, Louisiana, West Virginia, Massachusetts and Arizona.

Among other highlights:

- Over the past two years, the number of states that give citizens access to their state’s checkbook has increased from 32 to 46. In 2011, eight states created new transparency websites: Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Dakota, and West Virginia.

- Massachusetts’ new checkbook tool gives users the ability to monitor state spending in almost real-time because the data are updated nightly.

- Michigan linked its transparency site to an interactive map that tracks economic development incentives, allowing residents to learn about government-funded projects in their county, information about how specific companies will spend the funds, and the estimated number of jobs to be created.

- Louisiana’s Performance Accountability System has taken the lead on providing detailed performance evaluations of government agencies by listing specific agencies’ yearly objectives.

- Washington allows the public to see how specific areas of the state benefit from government spending by providing an interactive mapping tool with the exact locations of state-funded construction projects.

- Only one state — Illinois, which topped GJF’s 2010 subsidy disclosure ranking — provides information on both the projected benefits and the actual benefits created from economic development subsidies.

- Four states — Arkansas, Idaho, Iowa, and Montana — “have yet to post their checkbooks online.”

Report co-author Phineas Baxendall wrote recently on Huffington Post that states are suddenly as transparent to themselves as to their citizens:

“For example, based on information from its transparency website, Texas was able to renegotiate its copier machine lease to save $33 million over three years and negotiate prison food contracts to save $15.2 million,” he wrote. “Once South Dakota’s new transparency website was launched, an emboldened reporter requested additional information on subsidies that led legislators to save about $19 million per year by eliminating redundancies in their economic development program.”

The Department of Redundancy Department

As if on cue, our next and final stop on this transparency tour is the U.S. Government Accountability Office. This month the GAO has released two reports relevant to the corporate and economic development community. First came its second annual report to Congress identifying federal programs guilty of duplicative, overlapping or fragmented services. The report casts a spotlight on economic development programs in particular. Second: an analysis of DOE loan guarantees.

We’re about to look at the highlight reel. But the really impressive thing about true transparency is seeing clear through to the data itself. Thanks to the GAO’s navigable and accessible Web resources, you can do just that at the following two Web pages:

2012 Annual Report on Opportunities to Reduce Duplication, etc.: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-342SP

GAO report on DOE Loan Guarantees: http://www.gao.gov/assets/590/589210.pdf

The annual report for 2012 presents 51 areas where programs may be able to achieve greater efficiencies or become more effective in providing government services. The first report in this series, issued in March 2011, presented 81 opportunities to reduce potential government duplication, achieve cost savings, or enhance revenue.

Economic development receives strong focus from the GAO, starting with support for entrepreneurs, which may seem more like a mouse maze for entrepreneurs: The Departments of Commerce (Commerce), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Agriculture (USDA), and the Small Business Administration (SBA) administer 53 programs that focus on supporting entrepreneurs. “These programs, which typically fund a variety of activities in addition to supporting entrepreneurs, spent an estimated $2.6 billion in enacted appropriations on economic development efforts in fiscal year 2010,” says the report. Like corporations lately, the government may therefore have some candidates for consolidation — especially from among those programs that appear to barely track their own performance records.

Surface freight transportation is another area of economic development focus for the GAO: Congress authorized around $43 billion in fiscal year 2010 for Department of Transportation programs that can benefit surface freight transportation. According to the Department of Transportation, in 2007, the surface freight transportation system, which crosses multiple surface modes, connected an estimated 8 million businesses and 116 million households moving $12 trillion in goods.

“As GAO previously reported, federal goals in surface transportation are numerous and roles are unclear, and the federal government does not maximize opportunities to promote the efficient movement of freight, despite a clear federal interest, the billions of dollars provided, and the importance of freight transportation to the national economy,” says the GAO. (“No kidding,” say rail and truck professionals across the nation.)

“There is currently no separate federal freight transportation program,” the report continues, “only a loose collection of many freight-related programs that are embedded in a larger surface transportation program aimed at supporting both passenger and freight mobility. This fragmented structure makes it difficult to determine the types of freight projects that are funded and their impact on overall freight mobility.”

In fact, GAO could not determine the total amount spent on freight transportation projects because it is not separately tracked from other transportation investments. Nor is intermodal tracked, “which may result in funding projects across multiple modes without regard for how each works toward meeting a common goal.”

In the fomenting world of “green building,” GAO found in November 2011 that there are 94 federal initiatives to foster green building in the nonfederal sector. They’re spread across 11 agencies, with HUD, EPA and the DOE spearheading more than two-thirds of them. This table succinctly illustrates the overlap:

in the Nonfederal Sector

|

Green building element |

Number of initiatives |

|---|---|

|

Energy conservation or efficiency |

83 |

|

Indoor environmental quality |

60 |

|

Water conservation or efficiency |

51 |

|

Integrated design (collaborative planning at all stages of a building’s life) |

48 |

|

Sustainable siting or location |

43 |

|

Environmental impact of materials |

39 |

Another economic development office receiving intense scrutiny from the GAO is the Dept. of Labor’s Auto Recovery Office, established in June 2009 to help automotive communities affected by the sector’s dramatic downturn.

While some help has been there, GAO finds the office isn’t meeting its obligations overall and its performance is decidedly underwhelming — at least, in areas where GAO is able to find evidence of tracked performance at all. This reporter recently encountered one aspect of its activity when a report on repurposing auto plants, commissioned by the office from Michigan’s Center for Automotive Research, was nowhere to be found on the office’s website weeks after publication. The GAO recommendation?

“Unless the Secretary of Labor can demonstrate how the Auto Recovery Office has uniquely assisted auto communities, Congress may wish to consider prohibiting the Department of Labor from spending any of its appropriations on the Auto Recovery Office and instead require that the department direct the funds to other federal programs that provide funding directly to affected communities.”

Silos or Synergy?

There is evidence of progress already, however, in terms of better federal agency collaboration and a related behavior: simple communications.

In keynote remarks to the California Association of Local Economic Developers annual conference in Sacramento yesterday, U.S. Treasurer Rosie Rios, a former economic developer herself, was dismayed to see how few in the audience were aware of two Treasury programs: SSBCI and SBLF, both in place since the Sept. 2010 signing of the Small Business Jobs Act.

SSBCI alone has seen more than $1.4 billion approved across all U.S. states and territories, including a food manufacturer Rios and colleagues visited recently in California that has used the loan to purchase packing line machinery. That state’s SSBCI allocation alone was well over $168 million. Loans can be used to finance construction, acquire land, purchase buildings or acquire capital projects.

The SBLF provides incentives for mainstream banks to increase lending to small businesses. Rios said the administration’s budget calls for extending other programs as well, including stretching the New Markets Tax Credit program from its FY2011 allocation of $3.6 billion to $5 billion, and establishing a new manufacturing communities tax credit for communities experiencing major economic disruptions from losing a major manufacturing plant or military base.

But perhaps most promising among her statements was this:

“The federal government is trying to do a better job to make information as accessible as possible through websites and social media,” she said. “We recently launched a website to get information out to the business community — www.business.USA.gov. It’s a one-stop shop for the federal government.”

After her talk, Rios affirmed that the new website was indeed an illustration of improved federal agency collaboration.

Brian McGowan, a longtime California economic developer who recently left a post with the U.S. EDA to head Invest Atlanta, says his roots too are still as a local economic developer. Asked recently to reflect on lessons from D.C., he said it occurred to him while in D.C. that ” I wish I’d spent more time in D.C. as a local economic developer — especially in California, which didn’t tie well enough into what was happening at the national level.”

That’s clearly not the case in Atlanta, where McGowan works hand in hand with prominent Obama ally Mayor Kasim Reed.

“We were working hard — and it was directly from President Obama — to break down those silos and work together,” he says of his time at the EDA, citing interagency collaboration on the I-6 Challenge program, among others. He says agencies simply can’t afford to keep operating independently, whether they’re federal, state or local.

A lesson from D.C. and Sacramento, he says, is that “collaboration is powerful. One thing I really discovered in Sacramento is economic development organizations within regions who you think are working together, probably aren’t. Never make assumptions that people are collaborating, because collaboration is hard. In a period of severe austerity, it’s more important than ever.”

He saw successful examples of such collaboration across the nation during his EDA tenure, he says, including in Northeast Ohio, Pittsburgh and New Orleans.

“Our counterparts in Europe have been collaborating regionally for a long time,” he says. “So have our counterparts in China. It’s time for American economic growth organizations to reach out and collaborate.”

He’s working on that right in Atlanta, where he admits not all the players have been working as well together as they could: “One of my goals is to start bringing people together towards some common goals,” he says.

In other words, transparent partnerships can build a solid foundation of innovation, often springing from transparent sharing of information, objectives and hard data.

And while it’s easy to bellyache about Washington, the data at local fingertips is in just as much need of being shared with national officials as vice versa.

“I tell my colleagues across the U.S., we can’t rely on state capitals or the federal capital to solve our problems for us,” says McGowan. “We have to be willing to solve our own problems, to be creative, to be more collaborative. If you haven’t been working with your state or with D.C., they need you to reach out to them as much as they need to reach out to you.”