After the publication of IMD Smart City Index 2025, I conducted the following email Q&A with IMD World Competitiveness Center Chief Economist and Head of Operations Christos Cabolis. Before responding to questions, he offered this framing of what makes the report (SCI) unique:

“The SCI is not a measure of infrastructure per se,” he said. “It is a measure of how residents perceive the effectiveness of their city’s infrastructure and services, particularly whether technology is helping to solve the challenges residents face in daily life. This makes SCI a valuable input for policymakers and city administrators. SCI highlights whether a city’s efforts align with residents’ lived experience: whether residents feel policies are working, whether technology is accessible, and whether the benefits are widely felt across the community.

“If there is a disconnect, it raises a critical question,” he said. “Are city administrators solving a different problem that the one residents experience? Or is there a communications gap, where residents do not recognize the value of what is being provided?

Christos Cabolis

IMD World Competitiveness Center Chief Economist

and Head of Operations

The most striking rise in the upper echelon of your index comes from the two UAE cities and from Ljubljana, Slovenia … probably the least well known of all the top 25 cities. What is driving these cities’ rise in the rankings? And what do people need to know about Ljubljana?

Christos Cabolis: The rise of Dubai and Abu Dhabi reflects significant improvements in areas that matter most to the residents: health care, green spaces, digital access to public services and a general sense that the cities are becoming more livable. These are not just infrastructure gains. They are elements that are being ‘felt’ at the everyday level, and that shows in the data.

Ljubljana may be less well known globally but residents report high satisfaction with mobility, sustainability and public safety — that is, areas where many larger cities struggle. What is striking about Ljubljana is that it is performing well not because of scale, but because of responsiveness and perceived quality of life. This shows that cities do not need to be global giants to score highly. Instead, they need to make their services meaningful for their residents.

What are the leading factors causing cities to drop in the rankings?

Christos Cabolis: Cities typically drop when residents report growing dissatisfaction in one or more key areas. These are linked to affordability, congestion, safety or perceived gaps between available technology and actual access or impact.

In some large cities, even well-funded initiatives do not always translate into improved perception if the benefits are not visible at the neighborhood level or if services are not trusted or user-friendly. When residents feel the city is not working for them, it shows up in the rankings.

Your study’s methodology prominently relies on perceptions of residents. Are there particular examples that strike you where the perceptions don’t align well with observable reality (whether that reality is actually better or worse)?

Christos Cabolis: It is important to remember that in our index, perception is the reality we are measuring because it reflects the resident’s lived experience. A city might objectively rank high in broadband penetration or hospital capacity but if residents do not experience those services as accessible, affordable or effective, the perception will be low. Note that this is important feedback.

In some cases, this disconnect can be a sign that city administrators need to better communicate or localize their services or ensure that programs are not leaving segments of the population behind. In others, it may suggest that public trust is lacking even when technical infrastructure is in place.

We do not treat misalignment as a flaw. Instead, we see it as a signal. It invites a dialogue between what the city offers and what its people actually experience.

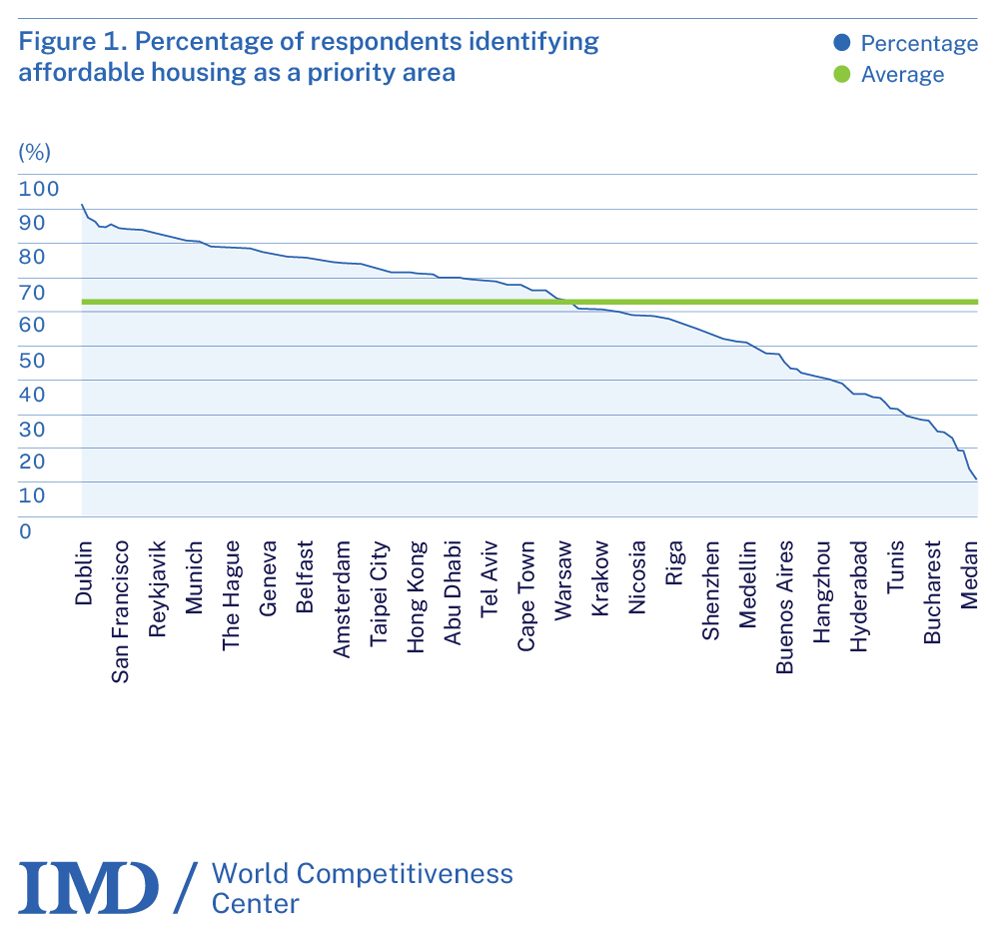

Graph courtesy of IMD

Affordable housing is a nearly universal concern. Which metro regions are devising the most effective or proactive solutions for attainable housing?

Christos Cabolis: Affordable housing is indeed one of the most widely shared concerns in SCI. In 2025, residents in 110 out of 146 cities evaluated identified it as a top priority and in some cities, up to 90% of respondents said they were unable to find housing for less than a third of their income.

Cities like Singapore, Vienna and Zurich are often cited for their proactive housing policies, from public housing models and rent control to land-use planning and digital tools that improve housing transparency. Yet even in some of these cities residents still perceive affordability as a challenge, showing that strong policy does not always translate into relief at the household level, especially in fast-moving markets.

Other cities, such as Dubai and Manama, have used large-scale investments and favorable ownership regulations to expand supply rapidly. And in these cases, residents are reporting a perception of improving affordability.

The takeaway is that effective solutions vary by context. The common thread in cities that perform well is a clear alignment between policy intent, execution and the everyday reality of residents.