I won’t make a blanket statement about the current State of the States — we know the economies and business climates of North Dakota and California are as different as those of the national economies of Germany and Greece in Europe. But of this I am certain: (1) the US, much of it at least, is a significantly more attractive location to invest in than in recent years, as the recent reshoring trend demonstrates; and (2) US states that demonstrate predictability and sustainability — in the economic sense — are the ones that routinely appear at the tops of business climate rankings, like the one Site Selection publishes each November.

“The best way you can be sure that a state will maintain [the tax credits and other incentives] you consider to be important to you is to have a state with its finances in order,” Gov. Nathan Deal of Georgia told me in October as I was working on the November 2015 cover story. “It’s predictability and stability, and investors want to be able to count on it for more than one legislative session. It’s smart for them to think like that, and it’s smart for us to understand that.” Georgia ranked first in our business climate ranking — for the third year in a row.

Meredith Whitney, who wrote The Fate of the States: The New Geography of American Prosperity (Penguin Group) in 2013, cited outgoing Gov. Mitch Daniels of Indiana as a state leader who understood this point. As the Hoosier State’s chief executive from 2005 to 2013, Daniels refused to cut into programs like education and infrastructure and likewise refused to borrow or raise most taxes at a time when state finances were not sustainable, as was the case in most states and remains the case today in many. Privatizing a toll road and leading the effort to make Indiana a right-to-work state are among Daniels business climate achievements while in office.

The bottom line, notes Whitney, is this: “As Governor Daniels describes it, businesses must believe in the sustainability of the state in order to locate there.” Like them or not, the steps Daniels took — and there were many — put his state in very good stead when viewed through the prism of economic development. “For Mitch Daniels,” writes Whitney, “doing nothing was never an option because he understood the velocity of money and realized just how quickly other states could exploit inaction.”

I would point to Gov. Scott Walker’s championing of the Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill in 2011 — controversial as it was, given its measures affecting funding of public union pensions and collective bargaining — as another example of a step taken to give businesses some confidence that future state budgets would not be unduly strained, and that the fiscal predictability investors seek was within sight, if not yet glaringly apparent.

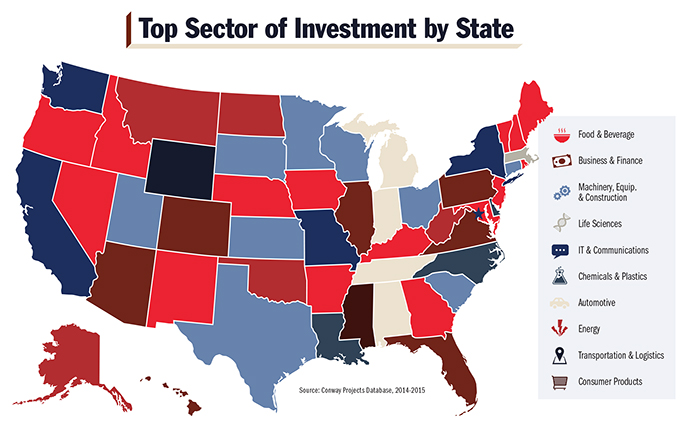

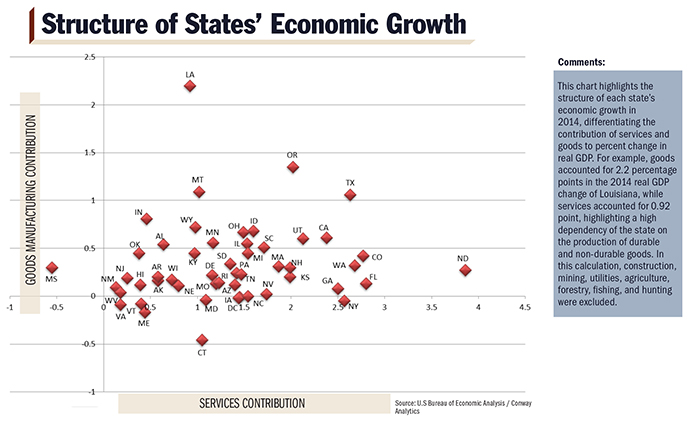

The point of Whitney’s book is this: US economic growth is predominantly found in flyover country — from North and South Dakota to Indiana to Oklahoma to Texas, in states that have found a way to attract corporate investment with fiscal discipline and pro-business policies in spite of economic pressure to reduce spending on social and other services. They have done this, to varying degrees, even in the wake of the Great Recession and the real estate bust of several years ago.

Pockets of this can be found outside this north-south economic corridor — North and South Carolina in the East and Utah and Wyoming in the West come to mind. No state is immune from fiscal pitfalls or without economic development challenges. But the state you do business in is either a contributor to US economic growth, or it’s a drag on it. Which do you want your operations in?

Where States Get it Wrong

The domestic energy boom has been a major contributor to state and national economic growth over the past decade — longer in places. But “not all of the central corridor’s advantages are geographical or geological,” writes Whitney. “They’re political too. The reality is, California could reap the same shale-oil and shale-gas bounties now benefiting North Dakota. Politicians simply choose not to.” Similarly, New York won’t take advantage of its natural gas reserves, which are not unlike next-door Pennsylvania’s, due to political disputes over fracking.

Meanwhile, why are companies — and their employees — moving in droves from California to Texas, to cite the obvious and well-documented example? (They are also moving key operations, if not always their headquarters, out of Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut, among others.) Site Selection story sources frequently point to destination states’ right-to-work status, workforce assets and energy costs. They also want a location where their employees won’t lose a disproportionate amount of their earnings to high property and other taxes. Does your state tax individuals on their earnings? Is your location’s cost of living a magnet for workers or a repellant?

On this point I am reminded of the weeks I spent in California’s San Joaquin County in recent years, working on large investment profiles that made the business case for locating operations there rather than in the costlier Bay Area and Silicon Valley, on the western side of the Altamont Pass. Tens of thousands of Bay Area workers traipsed across the mountains each day at o-dark-thirty to their tech jobs, because housing — living — was and is today far more affordable in San Joaquin. Their counterparts in Reno, Nev.; Omaha, Neb.; and Augusta, Ga., typically leave for work after the sun comes up, and their coffee is still warm when they get there.

Now What?

What will 2016 hold for the states and their ability to compete for capital investment? I’ve made the case that those with strong balance sheets deliver a stronger measure of fiscal predictability than those with seemingly insurmountable budget challenges. We chronicle in these pages throughout the year the motivations behind large project site decisions — and the reasons start-ups and small businesses choose the locations they do. New political leadership will influence the prospects of some states — Louisiana comes to mind, where a Democratic governor takes over the reins of a state run by pro-business, Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal since 2008. Louisiana’s rise in our business climate rankings and many others has been demonstrable. Can John Bel Edwards maintain that momentum?

I’m curious to know to what extent you and your location-selection team take into consideration this variable: Are the governors of the states in contention for your capital investment former business executives? Obviously, this shouldn’t be a deal breaker, but why not factor it in? If they were, then they already speak your language, the language of budgets, growth and of how to be successful.

It doesn’t mean that state will have the best business climate, at least not yet. Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner ran the private equity firm GTCR and a venture firm, R8 Capital Partners, prior to his election in 2014. His state has much room for improvement on the business climate front.

Some other examples worth noting are Rick Scott of Florida, a former chief executive of Columbia/HCA and venture capitalist; Rick Snyder of Michigan, former chairman of Gateway and venture capitalist; Doug Ducey of Arizona, former CEO of Cold Stone Creamery; and Charlie Baker of Massachusetts, a former CEO of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. Just as important, or more so, is whether states’ top economic development officials have the business experience to help new and existing businesses prosper. They either know how to do it, or they don’t.

You will find in these pages our most comprehensive State of the States analysis yet, complete with Conway Analytics visuals from Chief Analyst Max Bouchet, Site Selection editorial research on legislative activity of interest to site seekers and a variety of economic, workforce and other metrics and rankings to help you assess the lay of the land as this New Year gets under way.

Let me know how this analysis helped you in 2016, and what you think we should consider adding to it in the future. Your facility investment decisions are what make the states competitive — their business climates are only as strong as the projects they attract and the jobs those projects create. Thank you for making this guide part of your information-gathering process.