It’s going to take big spaces and big ideas to deliver humans to deep space. Pay a visit to NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, and you’ll see plenty of both, as the facility welds its space program heritage to a future that goes beyond the moon.

On the same former sugar-cane fields where the Saturn V rockets for the Apollo missions and the Space Shuttle’s external fuel tanks were constructed, work continues toward the planned 2017 inaugural flight test for the Space Launch System (SLS), described by NASA as “the most powerful rocket ever built that will take American astronauts into deep space, first to an asteroid beyond the Moon and eventually on to Mars.”

Mars is far in the future (the 2030s), but work on the machines and humans has already taken off. On November 23, NASA selected Aerojet Rocketdyne of Sacramento, Calif., to restart production of the RS-25 engine for the SLS, which will use four of the engines to carry the Orion spacecraft and launch explorers on deep space missions, including to an asteroid placed in lunar orbit and ultimately to Mars. The power generated from three RS-25 engines on the SLS equals the output of 12 Hoover Dams. The first four SLS missions will be flown using 16 existing shuttle engines that have been upgraded.

Under the $1.16 billion contract, Aerojet Rocketdyne will modernize the space shuttle heritage engine to make it more affordable and expendable for SLS. The contract runs November 2015 and continues through Sept. 30, 2024. Engine testing will be performed at NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi (just 40 miles from Michoud) and the SLS will launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., manages the SLS Program and the Michoud Assembly Facility. Jacobs Technology delivers manufacturing support and facility operations as a subcontractor. In July, the Syncom Space Services LLC (S3) team, comprising PAE Applied Technologies LLC and BWXT Nuclear Operations Group, Inc., was selected by NASA for the Synergy Achieving Consolidated Operations & Maintenance (SACOM) contract, a consolidation of contracts at Michoud and Stennis Space Center in nearby Hancock County, Miss. If all options are exercised, the maximum potential value for S3 is $1.2 billion.

Early this month, New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu joined city officials and business leaders to celebrate the completion of the $6.2-million Michoud Front Door Infrastructure Improvement Project, encompassing storm water management, roadway and lighting improvements designed to help create additional and continued private investment in one of the city’s key recovery areas in the Michoud neighborhood.

“This area of New Orleans East is an economic engine reinforcing that advanced manufacturing is key for the growth of New Orleans,” said Mayor Landrieu.

The project was funded by a federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), administered by the Louisiana Office of Community Development-Disaster Recovery Unit.

“The upheaval created by Hurricane Katrina threatened the economic viability not only of the city of New Orleans, but of the entire region,” said Pat Forbes, executive director of the Louisiana Office of Community Development-Disaster Recovery Unit. “The aerospace and defense industries are an integral component in maintaining the economic well-being of New Orleans, that’s why the state of Louisiana has fully funded this disaster recovery project, which lies at the front door of NASA’s Michoud facility.”

“Nearly every U.S. manned flight into space has had some component built at the Michoud Assembly Facility,” said New Orleans Business Alliance President and CEO Quentin L. Messer, Jr. “It is among the city’s most valuable infrastructure assets. With the completion of the Michoud Front Door project, our economic development prospects will now approach an entry that reflects this stellar history and the immense capabilities within.”

Resurrection By Diversification

In August, NASA named Bobby Watkins director of Michoud. The Alabama native brings to the job 30 years of NASA experience, most recently as director of the Office of Strategic Analysis and Communications at Marshall Space Flight Center, which manages Michoud. In an interview, he says one of his most important roles is maintaining a healthy working relationship with the community. Michoud has a $540-million impact on the local area in Louisiana and Mississippi, and supports roughly 5,400 jobs.

Noting the eight federal agencies currently on board at Michoud as tenants, Watkins says, “We have put a lot of resources into hardening this facility,” including higher levees and added redundancy for pumping stations. (Among the installation’s bragging points is that it was among the few places in Greater New Orleans that remained high and dry during Hurricane Katrina.)

Attracting commercial tenants who complement each other as well as potentially the government agencies is an important way NASA can get more bang for the taxpayer buck. An estimated 3,300 employees work at Michoud each day. Among Watkins’ responsibilities is ensuring the facility meets tenants’ needs as well as NASA’s, offsetting costs of maintaining the facility for the space program and helping ensure Michoud’s capabilities will be available to all when needed in the future.

“NASA does not have huge budgets like back in the 1960s,” says Watkins. “We try to leverage taxpayer dollars to the best of our ability” while also providing access to Michoud’s extensive assets in order to help those tenants be successful. “I’ve challenged my team to look at our current tenant base and incrase it by 20 percent by this time next year.”

Large-scale manufacturing is, of course, the primary target, encompassing such sectors as aircraft, automotive and shipbuilding. The 300 acres of available greenfield are available for an enhanced use lease (similar to leases companies have pursued on military bases under BRAC). Watkins’ team also is just beginning to benchmark against other US and foreign hubs for large-scale manufacturing, in order to improve efficiency and add best practices.

Once those tenants are there, they “become part of our family here at Michoud,” says Watkins, benefiting from on-site medical, security and fire services, among other amenities. He includes in that family the industrial park just across the road from Michoud’s entrance. “The more you can get those large-scale manufacturers together, the more you can get that synergy,” he says.

Hurdles are Opportunities

“Advanced manufacturing is thriving,” said Michael Hecht, president and CEO of Greater New Orleans, Inc., during a site visit in late October, and Michoud’s capabilities in the wake of the Space Shuttle program’s departure are a big reason why. “Seven years ago, there was concern that Michoud was going to get mothballed. We said it would be a more diversified, public-private facility.”

That sounded great as a plan, he said, but it’s actually coming to fruition. In addition to the SLS work, Michoud is home to the UK’s Blade Dynamics, a maker of huge composite blades for wind turbines that was just purchased by GE. In July Michoud shipped a 78-meter blade, the largest wind turbine blade ever manufactured in North America, from the port on site to Germany where it’s being tested.

Since Blade is a British company, there were some challenges in the beginning with regular access to Michoud by foreign nationals. But the Michoud team worked to get clearance requests from the traditional 30 days’ notice down to 10-12 days.

“We are always looking at ways to be efficient,” says Watkins, acknowledging that with Blade, “we crossed the hurdles early on. We have to follow those procedures, but we have policies in place” that can help accommodate requests within the bounds of federal restrictions from the Department of Homeland Security as well as ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations) concerning access to a NASA installation. Thirty days is still the official time period, but once a foreign tenant establishes a contractual arrangement, foreign national visitor requests become easier and more routine.

Other Michoud tenants include DNV (Det Norske Veritas); the US Coast Guard; Textron Land & Marine Systems; and Alabama-based B-K Manufacturing. The USDA’s National Finance Center at Michoud provides data center hosting, help desk support, human resources, and payroll services, processing a payroll of $1.7 billion for approximately 640,000 federal employees in 170 government agencies every two weeks. NFC employs approximately 1,000 full-time positions (not including subcontractors), and approximately 140 of these employees live in eastern New Orleans.

The Coast Guard liked it so much that in 2007 it started construction on an auxiliary base, investing $97 million in a facility that now has 300 people on site. Half of the deepwater port is used by the Coast Guard, and half by NASA. But even with those two tenants, the complex’s transportation assets are grossly underutilized.

MAF has half a million sq. ft. of office space available across its 36 buildings. The Michoud team hopes to announce a build-to-suit for an unnamed new tenant early in 2016. A likely arrangement for the build-to-suit will be a 99-year lease on the land, with the unnamed company owning the building.

Michoud is also home to Big Easy Studios, founded after Katrina by Herbert W. Gains and New Orleans entrepreneur Jerry Lathan. Among the films made at Big Easy are “GI Joe II,” “Ender’s Game” and “Jurassic World.” The investment came just as the winding down of the Space Shuttle program was leaving enormous spaces at Michoud unused.

Rocket Science

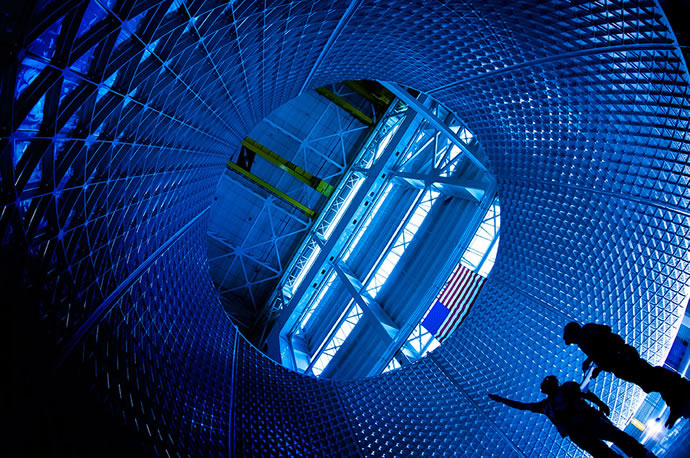

Walk through Building 103 (or, if you’re a regular, climb on a bicycle), and you’ll see there’s still plenty of unused space waiting for the thrust of new investment.

At Michoud, primary work on the rocket’s core stage is being performed by Boeing Co., pursuant to a $2.8-billion contract finalized in July 2014. Lockheed Martin is the primary contractor for the Orion crew module that will sit atop the rocket. The contractors are executing most of their work in sections of the cavernous Building 103, a facility with 43 acres under one roof. There’s still nearly 1 million sq. ft. available for manufacturing in that building, a slackwater port and plenty of other space and equipment waiting for full utilization at the 832-acre Michoud complex, including more than 300 acres of available green space. Building 318 houses a full metrology lab, available to all tenants on a pay-as-you-go basis.

A network of cranes navigates Building 103, while on its floor sits a collection of advanced manufacturing equipment that includes 37 machine shops, spray and paint booths, non-destructive evaluation, composite fabrication and cure facilities, and friction stir welding capabilities.

It’s also home to the Vertical Assembly Center (VAC), an advanced welding facility where 27.5-ft. diameter cylinders, domes, rings and other elements are being brought together to form the fuel tanks and core stage of SLS. Fueled by liquid hydrogen, the 321-ft., 5.5-million-pound rockets will be designed to carry payloads of either 70 metric tons or 130 metric tons — the latter option has 8.4 million pounds of thrust, equal to the horsepower produced in 208,000 Corvette engines.

The VAC is one of six welding tools being used to complete the massive project.

“One of the challenges that we face in building this large core stage is to develop world-class tooling using modern manufacturing methods in an affordable way, while maintaining the scheduled first launch in 2017,” said Tony Lavoie, then-manager of the Stages Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., said at the VAC’s unveiling. (He was replaced by Steve Doering earlier this year.) “This tool set that we’ve developed for Michoud to build the core stage is a perfect blend of those requirements and constraints.”

Too Late to Turn Back Now

In September, engineers at Michoud welded together the first two segments of the Orion crew module that will fly atop NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket on a mission beyond the far side of the moon.

“Every day, teams around the country are moving at full speed to get ready for Exploration Mission-1 (EM-1), when we’ll flight test Orion and SLS together in the proving ground of space, far away from the safety of Earth,” said Bill Hill, deputy associate administrator for Exploration Systems Development at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “We’re progressing toward eventually sending astronauts deep into space.”

What about the humans, you ask? Since the first astronauts were named in 1959, only 338 have been selected. In July 2013, after reviewing more than 6,100 applicants over a year and a half, NASA chose eight astronaut candidates hailing from places as diverse as Hoxie, Kan.; White Bear Lake, Minn.; Pomona, Calif.; and Caribou, Maine, to receive a wide array of technical training at space centers around the globe to prepare for missions to low-Earth orbit, an asteroid and Mars.

“These new space explorers asked to join NASA because they know we’re doing big, bold things here — developing missions to go farther into space than ever before,” said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden. “They’re excited about the science we’re doing on the International Space Station and our plan to launch from U.S. soil to there on spacecraft built by American companies. And they’re ready to help lead the first human mission to an asteroid and then on to Mars.”

Four more astronauts were named in July 2015 to take part in commercial crew module testing and missions to the International Space Station. But don’t put away that updated resumé just yet. After all, NASA is “in the process of identifying possible near-Earth asteroids to explore with the goal of visiting an asteroid in 2025.”

The next round of astronaut selection begins with an open application process December 14. The Astronaut Candidate Class of 2015 will report to Johnson Space Center in Houston in August 2017. One of the first things they, like every astronaut class, will do is tour every single NASA location — including the Michoud facility building their rocket ride, a mere 360 miles to the east.