| A |

mid threats that include residential encroachment, eminent domain backlash and logistics congestion, detail work has never meant so much in the assembly of large industrial project sites. But having those details in place can be the difference between a mega-project and mega-dirt.

Proof positive came in the fall of 2005 when SeverCorr chose a 1,400-acre (567-hectare) site in Lowndes County, Miss., for its new US$800-million mini-mill. That site was one of five that were part of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s megasite certification program, launched in March 2004 with the guidance of McCallum Sweeney Consulting. Four of those sites are therefore still looking for suitors.

By all signs, there are suitors aplenty, ranging from Kia Motors to Samsung to Toyota. If that sounds foreign to you, it’s because North America and the U.S. in particular are particularly attractive for investment right now, driven in part by exchange rates. But domestic investment is on the upswing too, driven in part by the American Jobs Creation Act of 2005, created to incite large U.S. multinationals to bring foreign earnings back to U.S. soil for reinvestment.

Site Selection surveyed its contacts in the 50 states, supplemented their responses with research, and put together the accompanying chart of super sites, defined as parcels of 1,000 acres (405 hectares) or more in size that are pre-disposed to industrial development. Site condition runs the gamut from “mostly forest” to business parks that keep their options open.

|

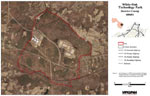

| This 2,735-acre (1,107-hectare) site in Stanton, Tenn., is expandable to 3,250 acres (1,315 hectares). It’s the largest of six super sites in the state. |

“We have a 9,000-acre [3,642-hectare] park and can put together 1,000 to 2,000 acres [up to 810 hectare] in one hour,” says Don Berger, marketing director for MidAmerica Industrial Park in Pryor Creek, Okla. “We would love to have a single end user,” says Barry Josowitz of Pittsburgh, Pa.-based The Rubinoff Company, speaking of the just-launched Starpointe Business Park in nearby Hanover Township.

At the same time, even Certified Megasites might be divisible by a prime number.

“In economic development, our goal is never to say ‘no’ to new jobs,” says David Rumbarger, president and CEO of the Community Development Foundation in Tupelo, Miss., home of the Wellspring site. “We have major-impact projects, which are $150 million of investment or 1,000 employees. If they qualify there, that’s a first step. Secondly, they could say, ‘Well, you have 1,700 acres [688 hectares], but we only need 350 or 300, but we are a major-impact project.’ If that is the right cluster — pharmaceutical or automotive such as a transmission or engine plant and not an OEM — that is enough of a foothold in that cluster that it could really develop the other acres that would be remaining. So based on that model, then part of that site might be available for that company. Since it’s 1,700 acres, and the Nissan site was roughly 900 to 1,200 core acres, you could lop off 200 or 300 acres and still have a major site for an OEM.”

Rumbarger explains that the overarching goal is to replace the region’s departing jobs in the $9 to $11-per-hour category with jobs in the $14 to $21-an-hour category, so anything that helps that along, including breaking up a super site, is fair game. However, he says, unlike super sites in Tennessee, Georgia and Kentucky, Mississippi state and local officials have been averse until now to purchasing the site outright. Rumbarger says publicly owned sites can help cut down money and time on the front end.

“The site selectors and the companies will tell you that what prevents them from making decisions are work force training and development and site preparation development,” he says. “Those two lead time items cost them tons of money, and they don’t really recoup it until five, 10 or 15 years down the road. Well, people are looking at year-to-year and quarter-by-quarter earnings. If you can gain an advantage on a competitor you’ll take it. That’s why we’re pitching for preparation of the site rather than leave it a greenfield. If we can get it under public ownership, then we can start the process.”

It was only a few years ago that Kentucky was in the driver’s seat for the Hyundai plant that ended up in Alabama. From many reports — and straight from then-Gov. Paul Patton’s mouth — much of the blame for losing that project lay at the feet of the Howlett family, who literally refused to sell the farm, and who very publicly fought the state and Hardin County in those entities’ invocation of eminent domain on their property in Glendale. In the interim, the issue of eminent domain has come to the fore in other states too, and splashed into the headlines in 2005 in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Kelo v. City of New London decision.

| Check out our first look at Super Sites, “Size Isn’t Everything,” from the January 2004 50th Anniversary issue of Site Selection. |

In a late 2004 e-mail exchange with Site Selection, Leon Howlett wrote, “Our family does not live in the dark ages. We understand the need for jobs and growth. But communities should have input into decisions that forever destroy or change them. Landowners should not have to endure the kind of abuse launched at our family. We were forced to fight a condemnation suit for an illegal taking of our property.”

Then Howlett shared the following quotation from Gov. Patton in the April 7, 2002, Courier-Journal: “The biggest thing I learned is that you don’t start promoting property for industrial development when you don’t already have agreements on the land. You just don’t do that, we don’t do that.”

“But in fact he did do that,” wrote Howlett.

Chances are, however, that nobody else is going to do that. Rick Games, president of the Elizabethtown/Hardin Co. Industrial Foundation, says there are no ongoing negotiations with the Howletts at this time. But he points out that the Glendale site’s famous missing parcel may not really be needed, given the layout of the site’s already substantial 1,551 acres (628 hectares). In the meantime, he’s been spearheading the crucial detail work.

“All of the buildings that were there have been removed from the interior, though we haven’t done anything yet to the houses on the periphery,” he says. “We’re doing the preparatory work, all the little small things that need to be done.” That includes wetlands delineation, and the state transportation cabinet is conducting a study on a possible new exit ramp off nearby I-65. The Glendale site is one of seven super sites in the Commonwealth.

Article continued below…

Click Photo for large image and information

| U.S. Super Sites | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Indeed, an Interstate interchange rivals dual rail capability as the super-site attribute most likely to raise site-seekers’ eyebrows. In fact, city and county entities in Chattanooga are just completing their second interchange for their Enterprise South site.

It’s figured into the mix in a big way in southwestern Illinois too. In Dupo, Discovery Business Park, a 2,000-acre (810-hectare) master-planned development, is still at an early enough stage to entertain the notion of a single large user.

“We also can expand up to another 2,000 acres [809 hectares],” says Tom Huftless, vice president of Clayco Realty Group, the project developer. He says the current site was assembled under long-term option contracts, with just a half-dozen landowners representing 95 percent of the land mass, which at this point is still farm land. But that land will soon be reachable via a brand new $19-million interchange on I-255.

“Currently we are in the process of getting our Access Justification Report submitted and approved by IDOT and the FHWA for the new interchange,” Huftless tells Site Selection. “Our time schedules show a completed interchange and rail overpass in three years. We can phase in infrastructure as deals mandate. The City of Dupo already has water and sanitary to the area. We will need to improve or develop new roadways depending upon the area of development. One of the key attributes of this site is that we are adjacent to a heavy concentration of labor (St. Louis). This is the largest undeveloped land mass within eyesight of the St. Louis Arch.”

There was plenty of local wrangling over exactly where that interchange would locate, as Dupo duked it out with nearby Columbia. In the end, says Huftless, Congressman Jerry Costello’s office was crucial in leading the decision-making that led to Dupo.

“One of the key decision criteria was the creation of jobs and types of jobs — industrial, distribution, light manufacturing — that the Dupo/Clayco plan could bring to the region,” says Huftless. “Another factor was the type of interchange to be built. The competing interchange [Fish Lake], because of its placement near the intersection of Rte. 3 and I-255 with its merging traffic lanes, mandated a half-loop system which inherently can handle a limited set traffic flow. Dupo is analyzing the merits of developing a single-point interchange which has a much less obtrusive footprint and is commonly known as a high-traffic interchange.”

High traffic is a notion that just about any super site will welcome.