By 2050, global demographics will look very different — older and wiser, mostly.

The transformation is already underway. Over the next six years, increasing life expectancy coupled with decreasing fertility rates will push the global share of the population aged 60 and over to one in six. This figure will soon double, with 2.1 billion people expected to celebrate aging out of their prime working years by 2050, according to projections from the World Health Organization.

The other 2.1 — the replacement fertility rate — will become an increasingly aspirational figure as birth rates decline around the world, and with them the proportion of the working population. Already evident among the labor pools of several highly active manufacturing destinations in East Asia and Europe, the next demographic disruption will have drastic repercussions for the global labor force in the not-so-distant future.

In other words, old age is coming for us all and will impact global manufacturing destinations.

Aging Populations, Shrinking Workforces

Europe is grappling with a shrinking workforce. As of last year, the median age in the European Union was 44.4 and rising, 14 years older than the global median. Eastern Europe is preparing for up to a 35% reduction in the number of working-age citizens, and not a single EU member state has a fertility rate above replacement. This story is not unique.

Home to the greatest concentration of greenfield FDI, Asia also stands at the forefront of the demographic transition. In South Korea, Singapore, Japan and Thailand, fertility has already fallen well below replacement rate. By 2050, Korea’s dependency ratio, or proportion of those above and below prime working age, will more than double to be one of the highest in the world. Falling closely behind with a current fertility rate of 1.3 and dropping, Thailand is set to halve its population and double its number of seniors over the next 50 years. Since 2022, deaths outnumber births in China for the first time in six decades, despite fervent efforts to reverse the country’s one-child policy. Even Vietnam, with its relatively young and active workforce, is growing up, albeit at a slower pace.

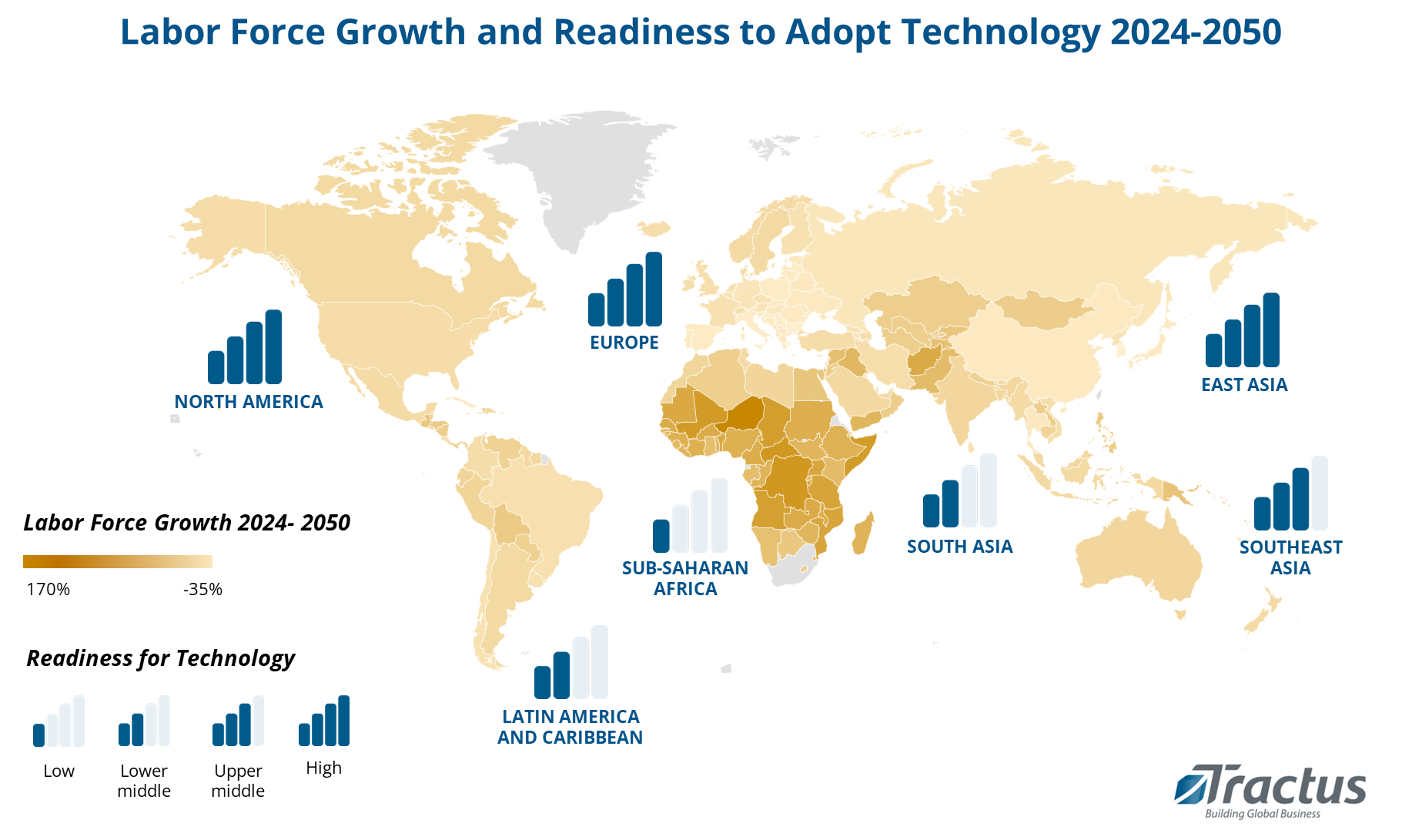

Sources: World Bank, Network Readiness Index, Tractus Analysis

Europe and Asia provide a preview into the coming decades for the rest of the aging world. Japan, considered a “super-aged” society with more than 20% of its population 65 years or older, already faces slowing growth caused by weakening productivity and a growing strain on public finances, as health care and pension expenditures swell while the nation’s tax base shrinks. Although South Korea is slightly younger than Japan, it has the lowest fertility rate of any country in the world, drawing understandable concerns for its future workforce. Germany currently struggles to find skilled workers as it stares down the prospect of a labor shortage in the neighborhood of 7 million people by 2035. These examples highlight only a few of the challenges currently facing major manufacturing destinations that will only worsen without intervention.

The dwindling pool of young, able-bodied workers affects productivity and puts pressure on labor-intensive industries. If left unchecked, this will lead to rising production costs and supply chain disruptions across key industries, eroding the competitive edge of even the most attractive manufacturing destinations. These nations must find innovative and equitable solutions to not only address the imbalance between a depleting workforce and the demands of the manufacturing sector, but also to sustain the health and wellbeing of their aging and vulnerable citizens.

The Demographic Divide

In spite of the foreboding global trend, not every country is shrinking. Africa at large is witnessing a surge in population growth, with estimates for 2050 indicating that one out of every four individuals globally will be African, a rising proportion of those working age.

Asia also still has labor-driven markets. South Asia continues to boom, with India, Pakistan and Bangladesh expecting a combined 30% population increase by 2050, even with a downtick in fertility rates. India, the most populous nation, is projected to continue growing until 2064, at which point it may hit a staggering 1.7 billion. Over the short term, the region will maintain some of the highest GDP growth rates in the world. In Southeast Asia, Indonesia and the Philippines will continue growing and have relatively stable labor forces.

Of the myriad other countries that are aging, some are maturing much more slowly, with fertility rates that hover just below replacement levels or populations that are growing at more modest rates. Such is the case in the United States and Mexico.

Other regions such as Latin America are less clear cut. Although the larger economies of Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Chile are aging just behind Europe — and Puerto Rico has a fertility rate akin to Korea’s — much of the rest of the region is relatively stable or even expecting labor force growth.

Striking a Balance

The traditional answer to the problem of a shrinking workforce dictates that global manufacturers look for labor arbitrage opportunities and migrate toward those countries with more human capital. The countries that are expecting growth, or even stability, in the coming decades offer varying degrees of opportunity for labor arbitrage. The countries that are not will need to adapt in other ways.

To stay competitive against countries with larger workforces, maturing nations have a few options. They can race to proliferate, joining much of East Asia and Europe in incentivizing larger families. Unfortunately, these policies historically have had little impact. Higher participation rates of women in the workforce have helped push back the median age at which women give birth, and in most places, incentives do little to provide the stability and balance working families need over the long term, nor do they cut costs significantly. The costs of raising children in Korea and China remain the highest in the world.

Another option is to force an immediate correction and follow France’s lead in simply compelling citizens to work longer; last year, France pushed its national retirement age from 62 to 64 in a highly controversial move.

While time will tell whether these policies are effective at increasing the labor pools, a necessary alternative for many aging manufacturing locations is to meet the workforce where it is, supplementing the losses through automation, digitalization and immigration.

Automation offers improved efficiency, safety and economic competitiveness. By automating routine and physically demanding tasks, industries grappling with workforce shortages can optimize human capital and create a more inclusive workforce. Moreover, the prohibitively expensive costs for automation, robotics and AI are dropping rapidly, opening the playing field for more countries to participate.

Digitalization facilitates upskilling and remote work opportunities, accommodating the needs of older workers and fostering their continued contribution to the labor market. Physical and cognitive augmentation can achieve a similar effect, equipping those who are typically excluded from the market with the tools to contribute their skills and experience.

While automation and digitalization will empower a more inclusive workforce, readiness to adopt technology varies by country, and not every region can — or should — make this change in the near term. For less technologically advanced countries, reimagining immigration policies will be vital to mitigating the effects of the demographic disruption on industry, but acceptance of the need to allow lower-skilled workers to immigrate may prove challenging. Striking a balance between welcoming skilled and young workers will be essential to filling gaps at all levels.

Winners and Losers

Who wins and who loses from the demographic disruption will depend on how quickly individual countries can adapt to their changing circumstances. Even where labor is abundant, countries face their own problems such as lack of education, gender inequality, weak health-care infrastructure, conflict and political turmoil — all of which will inform investment decisions in the years to come.

Europe and North America will benefit the most from a combination of technology and immigration. Both regions have the capability to automate, which will help build more inclusive workforces. Additionally, while North America is in a less hurried position, the United States and Canada will have targeted labor needs that vocational education and immigration can help fulfill. This is already the case, as evidenced by the skilled labor shortage facing TSMC’s new Arizona plant. After having to postpone manufacturing due to a shortage of skilled labor, the Taiwanese chipmaker recently sent an undisclosed number of workers from Taiwan to the United States to get the fab up and running.

Historically less popular for manufacturing investments due to political and economic instability, security concerns, and overall lack of competitiveness against the technology and labor arbitrage opportunities offered by Asia, Latin America has the potential to emerge from the demographic disruption relatively unscathed. Whether it can use this time to capture the manufacturing demand remains to be seen.

Much of Asia will be forced to accelerate adoption of technology. Japan and Korea already have a head start. Chinese companies similarly excel in this area, and it will be up to the Chinese government to nurture innovation through job creation and providing funding and other soft support.

Meanwhile, Southeast Asia will be a battleground for skilled labor. In the comparable markets of Vietnam and Thailand, Vietnam has the overall labor advantage, but Thailand’s more developed business ecosystem remains attractive. Whichever country adopts technology the fastest may be the winner of their shared targets such as EVs and batteries. Indonesia and the Philippines, on the other hand, may be less tech-driven as their labor arbitrage opportunities will be sufficient to attract foreign investment.

In its effort to close a skills gap and attract more talent, the Thai government aims to attract 1 million foreign experts, remote workers and high-wealth individuals over the next five years through its long-term visa program. Loosening restrictions on “highly skilled” employees, as Malaysia has done, can pave a longer runway for these countries to adopt technology, helping them stay competitive as they advance.

By all accounts, India should be the winner of the demographic disruption. With its burgeoning and tech savvy workforce, the nation is poised to capture a significant portion of global manufacturing investments.

A New Age of Manufacturing Competitiveness

Regardless of where a country ranks on labor availability, technological readiness, education or stability, the risk posed by the looming demographic disruption to manufacturing investments worldwide demands extensive planning. Luckily, unlike most other risks, this one is relatively predictable.

The aging demographic adds a layer of complexity to the already intricate landscape of labor availability impacting corporate manufacturing location decisions. Economic development organizations will require strategic approaches to ensure attractiveness, continuity and competitiveness of manufacturing in impacted regions.

Placing innovation at the center of the solution paves the way for public/private sector collaboration and augurs well for a more adaptable and resilient workforce. With age comes knowledge and, if knowledge is power, then technology is the catalyst to unleash it.

John Evans is Managing Director and Sarah Urtz is Senior Research Analyst at Tractus. Tractus has been assisting companies in making informed decisions about where to invest and how to expand their business in Asia and beyond for over 25 years. For more information, visit www.tractus-asia.com.