Think the cloud is a soft, pillowy, catch-all for all your data storage needs and worries? Think again. For every load of big data, you need heavy-duty physical infrastructure and power to ship and store it.

Since January 2014, Site Selection’s Conway Projects Database has tracked 368 data center facility investments around the world, driven by regulations as well as by hard infrastructure to locate as close as possible to clients and traffic. The leading investors are a mix of top colocation developers (led by Equinix and Digital Realty Trust) and the tech enterprises you’d expect to find in need of more data space: Google, Facebook and Apple among them. The king of them all is Microsoft, whose Cloud service hosts 80 percent of the Fortune 500, and which aims to reach an annualized commercial cloud revenue run rate of $20 billion by FY 2018.

That takes hard assets. In early October, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said at the beginning of a four-day visit to Europe that the company has more than doubled its cloud capacity in Europe in the past year, has invested over $3 billion across Europe to date, and intends to deliver the Microsoft Cloud from data centers in France, starting in 2017. “These new investments in cloud are helping customers — including the UK Ministry of Defense, the Renault-Nissan Alliance, Ireland’s Health Service Executive and ZF from Germany — to innovate in their industries and move their businesses to the cloud while meeting European data sovereignty, security and compliance needs,” said a company release. The company also released a book, A Cloud for Global Good, that “outlines a roadmap for working with policymakers to build a cloud that is trusted, responsible and inclusive.”

“Data sovereignty laws are redrawing the global data center location map,” said a JLL data center trend report in July. “From Brazil to Russia, the industry’s biggest players are expanding internationally faster than ever to meet growing demand and help users stay compliant with regulations designed to keep data inside a nation’s borders.”

Irish Ayes

Nadella made his announcement in front of 2,000 business leaders, developers and entrepreneurs in Dublin, Ireland, where Microsoft has invested in a data center hub. Another hub is located in the Netherlands, and other locations continue to grow in Austria and Finland. Meanwhile, the company has rolled out UK data centers in Cardiff, Durham and London.

Microsoft is not the only large enterprise data center investor making large bets on Ireland. Last January, Facebook — whose international HQ has been there since 2009 — announced that Clonee, County Meath, will be the site for its newest data center. The Clonee data center will be its first in Ireland and follows Luleå, in Sweden, as its second in Europe. The sustainability mandate was loud and clear.

“Our data center in Clonee will be powered by 100 percent renewable energy, thanks to Ireland’s robust wind resources,” said Facebook. “This will help us reach our goal of powering 50 percent of our infrastructure with clean and renewable energy by the end of 2018.”

Facebook also has announced a new data center in New Mexico that will be 100-percent powered by renewables such as wind and solar (see Southwest Review of this issue).

Cloud-based titles are nearly as popular as cloud-based computing itself. Also in October, the non-profit Good Jobs First released Money Lost to the Cloud: How Data Centers Benefit from State and Local Government Subsidies. Most territories know the jobs are scant but the tax base is rich when it comes to data centers. But based on its examination of a handful of data center megadeals, Good Jobs First says it’s not worth the chase.

“States and localities are giving cash-rich tech giants an average of $2 million per job for data centers the companies must build to run ‘the cloud,’ “ says the group, which recommends capping subsidies at $50,000 per job. “Our main message to state and local officials: You should be absolutely stingy in dealing with a possible data center siting,” said the report. “Internet-based companies have to grow the cloud and they will choose stable areas with cheap electricity. They will barely benefit your local economies because they create so few jobs and often import top-wage labor. If tech corporations also demand $2 million per job in subsidies, taxpayers will incur huge losses. No private party would agree to a bargain with such high costs and such low benefits, and you would be wise to refuse such demands.”

Vicious and Virtuous Cycles

How much energy do data centers use? More every day, it seems, despite their proprietors’ best efforts. The US Dept. of Energy said in June 2016 that 70 billion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity were used by US data centers in 2014, an amount equal to 2 percent of the country’s total energy consumption or the annual power use of 6.4 million average US homes — homes that, of course, are using their own prodigious amounts of power to access the Internet those data centers facilitate.

But it could have been a lot worse.

According to the DOE, the total 2014 power usage represented a 4-percent increase since 2010. That’s a big improvement from 24-percent growth in power usage during the preceding five years, and 90-percent growth during the five years before that (2000-2005). Without the efficiency improvements, said the study from the DOE, Stanford University, Northwestern University and Carnegie Mellon University, that 2014 total would have been more like 110 billion kWh.

“Based on current trend estimates, US data centers are projected to consume approximately 73 billion kWh in 2020,” said the DOE. That total could be reduced by up to 33 billion kWh if additional energy efficiency strategies are implemented.

Sometimes the data center space is part of a larger site. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) in October released insights from its most recent Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey that showed that computing electricity intensity (which includes electricity used by servers and data centers, in addition to desktop computers, laptops, and monitors) is 35 percent higher for buildings greater than 200,000 sq. ft. (18,580 sq. m.), and three times higher for all other buildings, says the EIA.

Nonetheless, territories want them. In some areas, the more the merrier.

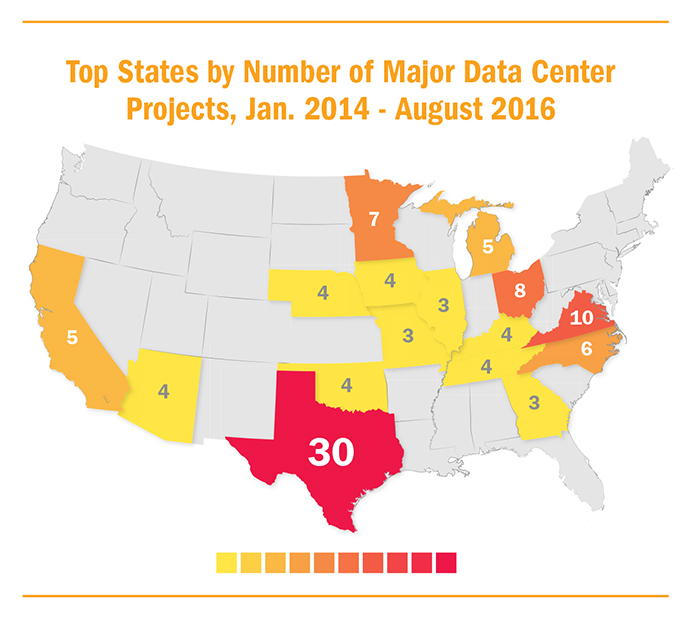

In October, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe announced that French company OVH, the leading cloud provider in Europe, chose Virginia over North Carolina to invest $47 million in its North American headquarters and first US data center in the very French-sounding Fauquier County. The company will install dark fiber infrastructure in an existing facility in the Vint Hill Business Park. McAuliffe credited a meeting with OVH during a 2015 trade mission to Europe, as well as an IT infrastructure in the Commonwealth that has made it the home of nearly 600 data processing and hosting centers. OVH operates 250,000 physical servers in 17 data centers across three continents.

Virginia Secretary of Commerce and Trade Todd Haymore called it a win-win because of OVH’s planned investment in infrastructure enhancements at the business park that will open access to the development of nearly 150 acres (60 hectares) with increased fiber, sewer, water and electrical capacity. “It is exciting to watch Virginia grow as a leader in the data center industry, which has accounted for more than 7,600 jobs and $9 billion in capital investment since 2005,” he said.

Canadian Firm Focused on Plug-and-Play

A former technology leader for Canadian telecom and media giant Rogers has founded his own company in Hamilton, Ontario, to directly address the challenges of wasted energy and wasted capacity. Cinnos (Canadian INNOvation Systems) calls its Smart MCR product “the first truly scalable, all-in-one mission-critical rack that grows with your needs.”

Helping develop it and other Cinnos products is the Cinnos-McMaster Computing Infrastructure Lab, a first-in-Canada hub for data center R&D that was established in collaboration with the Faculty of Engineering at McMaster University. In a sector not known for its job creation, Cinnos is trying to muster the opposite dynamic.

“From our industry’s point of view, I think we’re creating more manufacturing opportunities,” said founder and CEO Hussam Haroun at a panel discussion in Hamilton in early October before business, trade and economic development leaders from 27 nations taking part in the Americas Competitiveness Exchange. “We’re trying to make a data center a pre-fabricated box.”

“We’re looking at ways to make our rack intelligent and our industry intelligent,” says Haroun in an interview. “We want to make it a global appliance product.”

The company has now grown to 31 employees, while growing sales by more than a factor of 20 year-over-year since its launch. And why did it launch?

“Today, DC construction is a $100 billion+ market. DC owners, however, have been plagued by the enormous upfront costs ($1M+ per data center), slow deployments (12-24 months), as well as very high operating costs,” the company explains. “The high barrier to entry has prevented many potential technical innovations from gaining market traction.”

Cinnos claims to be making mission-critical data centers accessible to firms of all sizes by using the same modular approach you’d use with Lego blocks — only these blocks come with pre-engineered components, and don’t cost millions of dollars.

Tangible Results

“The ‘secret sauce’ in the mix is a smart control system that employs an array of sensors and layers of intelligent algorithms to eliminate wasteful over-design requirements that are rampant in legacy DCs,” explains the company. Using a raised floor, says Haroun by way of example, “has become a very inflexible way of designing data centers because it cannot evolve as fast as the needs of the IT equipment. Raised floor is designed based on an average capacity per cabinet and is a permanent installation that can’t be modified once it is built.” Its infrastructure also tends to be very expensive.

Some are moving away from raised floor, but some continue to use it “because they feel that they can predict the future,” he says. “But we are finding that they are not filling the data centers as fast as they think or running out of capacity, and now they have to do major construction to modify existing space, or even abandon their existing space to build a new one and leaving the older space underutilized.”

Haroun cites measurable results from one large company: “One of our customers budgeted to deploy a multi-cabinet deployment over a 50-cabinet data center within six months, but then they faced capital constraints and they were asked to reduce their expenditure substantially and still find a way to deliver to their customer,” he explains. The Cinnos solution allowed the client to defer capital by 90 percent and deploy only what they need their first year, while saving around 40 percent of the total cost of ownership of the full deployment, “and they can do it within weeks.”

The company launched its product line worldwide in October 2016 at GITEX, the world’s largest IT exhibition in Dubai. Haroun says Hamilton will continue to be the company’s base for R&D, design and manufacturing.