L |

ocation searches frequently focus on the larger metropolitan areas, and for good reason. Data sources are more readily available for these locations, and they represent the largest labor markets, airports, developed properties and other resources. However, there is a whole other layer of locations the small towns — that represent communities with populations of 10,000 to 50,000. Small towns may lesser known or located in more remote areas, but take a closer look — you may be pleasantly surprised.

The index of a good atlas proves there are many hundreds of these communities scattered throughout North America. They appear only as small dots on the map, but for the millions of local residents living there, these communities represent places that support business and a quality of life that would be the envy of many big city executives and commuters.

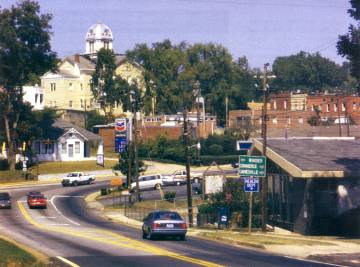

Small towns are not all the same, but they can be categorized by the type of economic base that is in place. The typical “anchor stores” or major economic segments that underpin these smaller communities represent a fair amount of diversity. Examples include large military bases, such as Robins Air Force Base outside Warner Robins, Ga. (pop. 46,000); Concord, the state capitol of New Hampshire (pop. 38,000); university towns, such as State College, Penn. (pop. 40,000); corporate headquarters, such as Whirlpool Corp., in Benton Harbor, Mich. (pop. 12,000); resort and retirement communities in the mountains or near the ocean, such as Myrtle Beach, S.C. (pop. 26,500); or manufacturing communities, such as Waynesboro, Va. (pop. 20,000).

Many of the small towns have more than one segment as an economic base. For example, Keene, N.H. (pop. 22,500) has Keene State College along with several manufacturing firms and two regional insurance companies. Some of the larger technical and research universities, such as Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va. (pop. 35,000), and the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, Mass. (pop. 18,000), have well-developed technology parks that have attracted numerous employers into the area to leverage the expertise and labor available through the local university. Companies with call center operations have successfully located in college towns, such as Morgantown, W.Va., (pop. 27,000), and near military bases to leverage the student and spousal labor resources that are available.

Big Company, Small Town

Moran, Stahl & Boyer recently surveyed Fortune 500 companies that have their headquarters in small towns to gain insights into the opportunities and challenges such a location generates. Most of the relevant companies have resided in their hometown from the founding of the company, ranging from 22 to over 130 years ago. Over time, the company and the town have built very strong relationships that have evolved into a shared culture and identity. The company usually provides some type of on-going community support in such areas as education, the arts, sponsoring special events or making contributions to major community facilities projects.

The company may also be active in local Chamber of Commerce initiatives, including economic development. In contrast to the “company towns” of the early Industrial Revolution, companies no longer want to “own” the town but rather be a contributor to its quality of life and economic vitality while leaving the basic infrastructure and operational needs with the local town government.

Companies surveyed noted that they need to be very cognizant of any rapid growth or downsizing that can have a drastic impact on local resources. For example, rapid growth may stimulate the need for more housing and schools than the community can produce in a short time period. Local labor resources are finite and can result in recruiting challenges if tapped too frequently. Rapid downsizing can have an immediate impact on housing prices, overall unemployment numbers and community welfare. Essentially, large employers in small towns need to manage their employment levels — either up or down.

The ability to recruit and retain top talent may pose problems depending on the location. Employers and new recruits coming into a smaller town have similar concerns related to availability of housing, health care for special needs, sports and cultural activities, quality of school systems, opportunities for spousal employment and job options. In many cases, small towns have answers to many of these needs although they may be in a slightly different package from what the recruiter is familiar with.

For example, the local college may provide great spectator sports instead of pro sports in the big city, or a local clinic may have the medical specialization that is handled in a major hospital in a metropolitan area. Cultural events may be offered at the local college or a small civic playhouse and shopping may be done more over the Internet or at a regional mall.

The upside of a small community — a less hectic life style, 10-minute commutes, easy access to outdoor activities and a stronger sense of community — can be very strong differentiators for recruiting talent to the company and keeping employees productive.

From the Community Perspective

Moran, Stahl & Boyer recently surveyed selected small towns located throughout the east coast and Midwest to understand their perspective on economic development and their strategy for attracting additional employers. In general, there was a common interest in high-tech companies and light manufacturing with low environmental impact. There was less interest in the mega-manufacturing operations like those that arrived in the 1950’s and ’60’s and have since gone through substantial downsizing. To the towns, a portfolio of small to mid-size companies that are stable are ultimately more valuable than one large employer whose employment level fluctuates.

A number of the communities would prefer to stay with their manufacturing heritage, but most feel they will ultimately need some type of back office or knowledge-based businesses to survive long term. Their link to an interstate is still very critical, because it potentially brings tourism and provides an opportunity to expand into distribution if they have the required low-cost, flat land and logistical positioning.

Small communities have a sincere interest in growth, but they want to manage it better than the larger cities have. New business should be placed in pre-defined industrial parks or in renovated buildings rather that scattered around the community at random, most maintain. For some communities, land is a premium — particularly flat land — and they want to maximize its use. Current employers in each respective community have an interest in growth as long as the new businesses complement their operations.

|

Local attributes and resources typically marketed by small communities include the size of the labor-draw area, because traffic is minimal; the strong work ethic and low turnover of their workers; and an exceptional quality of life with low crime, low-cost housing, clean air, short commutes and unique cultural and recreational opportunities. Many small town school systems have very good ratings, but quality will vary among areas.

The marketing of small towns utilizes a number of techniques. Major utilities as well as state, regional and local agencies sponsor economic development initiatives. Many towns have their own Web sites, place ads in trade journals and target mailings to site selection consultants. They also use feature articles in major metro Sunday papers to promote unique attractions in their area to entice tourism and potential companies to come and visit.

A Case Study: Corning, N.Y.

This study begins back in the mid-19th century, when the founder of what became the Corning Glass Works, Amory Houghton, relocated his business to Corning, N.Y., in search of better access to raw materials and lower operating costs. Since 1868, the Corning Glass Works (now known as Corning Inc.) has enjoyed a strong relationship with the local community that has helped the company and community prosper. Together they have lived through rapid growth and downsizing, devastating floods, urban renewal, visits by famous people and the ebb and flow of daily life.

Corning is now a multi-billion dollar corporation with facilities around the globe. But it still has its corporate and division headquarters, flagship R&D operation, corporate engineering and corporate support services operations in Corning, N.Y., an area with a population of about 20,000 residents.

From the perspective of Tom Blumer, a 28-year veteran executive with the company as well as a local resident of Corning, N.Y., the small community works well for the company, because the values of the company and the values of the community are almost synonymous. Team work. Fair play. Honest business practices are all hallmarks of Corning, Inc., and can be found in the local businesses that surround Corning’s headquarters. A sense of community is reinforced by the small town location, says Blumer.

However, Blumer cautions that being a major employer in a small town brings unique challenges. Recruiting top caliber optical communications technologists is more difficult, for example, but it can be done with hard work. Helping local community leaders with infrastructure management to support growth can also be a challenge. It is important to help without being perceived as actually doing their work.

The opportunity for economic diversity is more difficult in a small community with a major corporation headquartered there. It is vitally important to encourage economic diversity, Blumer adds, as other firms can offer spousal employment opportunities, absorb some amount of Corning’s employment fluctuations, as well as being another partner in the community.

Small towns are not the answer to all location decisions, but they have a place in the company location portfolio. Placing back-office operations, call centers and data centers in small towns that have reasonable labor resources and telecom access can result in both lower operating cost and risk as well as access to a highly committed work force. In some cases, there are very attractive incentives available that include various tax abatements and credits, grants for infrastructure and training provided through local community colleges. Manufacturing and distribution operations have also been placed in smaller towns with good results as long as the local resources and logistical positioning match the needs of the company.

Locating a business operation in a small town requires careful evaluation, and being a major player in a small town brings special responsibilities. But as many companies that live in small towns would confirm, they are proud of their “hometowns,” and the community has been part of making them a success.

John M. Rhodes is president of Moran, Stahl & Boyer, LLC,

an Atlanta-based site selection and relocation consulting

firm. His email address is john.rhodes@msbconsulting.com.