Community colleges have done a lot to boost graduation rates and program completions. But it’s not enough.

Davis Jenkins, Senior Research Scholar, Community College Research Center, Columbia University Teachers College

David Bevevino, Research Director, Aspen Institute College Excellence Program

That was the message delivered by Davis Jenkins, senior research scholar at the Community College Research Center (CCRC) within Columbia University’s Teachers College, and David Bevevino, research director in Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, at the fall 2022 symposium of the Institute for Citizens & Scholars Higher Education Media Fellows program.

“We’re very interested in looking at guided pathways,” said Jenkins. Community colleges “have done a lot to get students through, but now they need to look at their programs. Their outcomes haven’t been very good.”

The good news? Between 2006 and 2015 there was a 24% increase in the six-year completion rate for students who start at a community college (to 42%). The discouraging news? Only about 25% of associate degree graduates and a bit more than 33% of certificate holders earned enough pay to qualify as “good jobs,” defined as those that pay a minimum of $35,000 for workers between the ages of 25 and 44 and at least $45,000 for workers between the ages of 45 and 64. Even worse, most community college starters do not earn any credential.

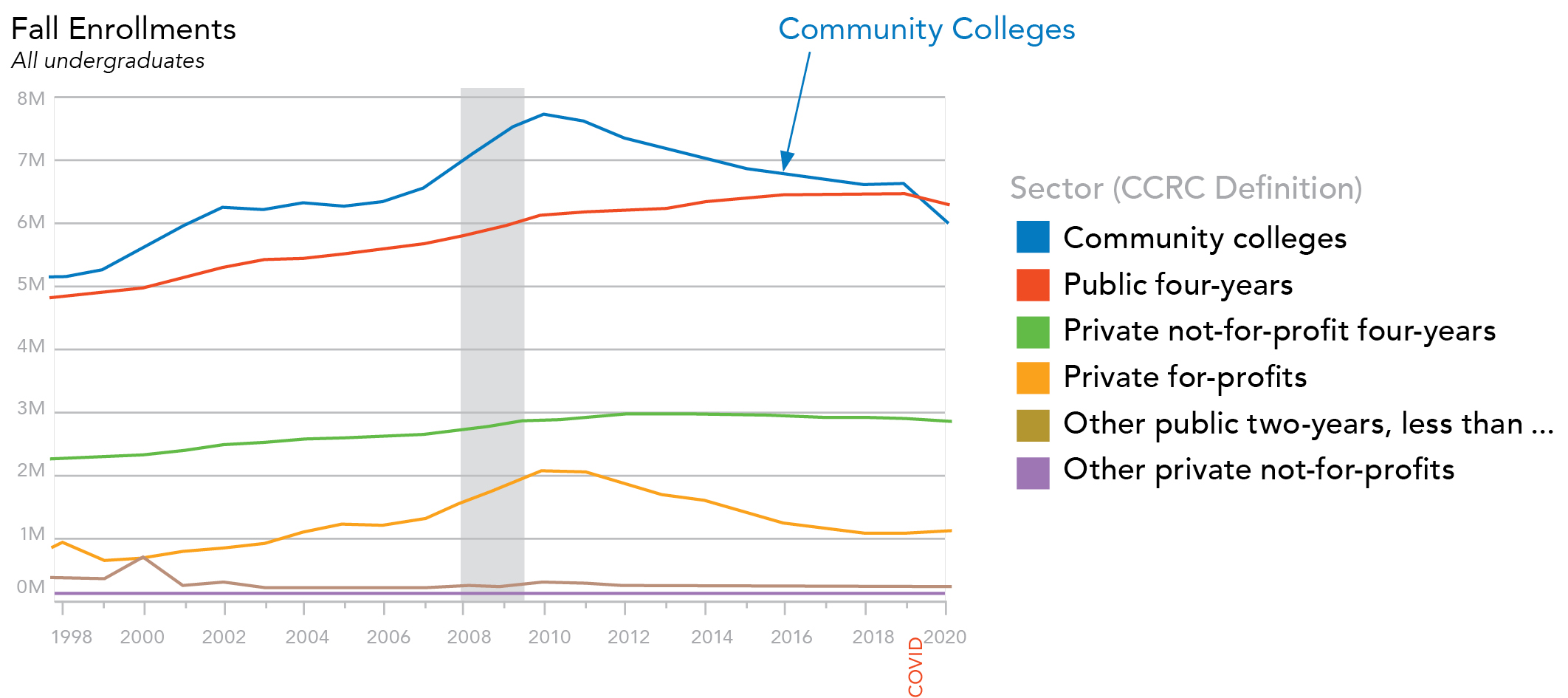

As community colleges lose out to public 4-year colleges in the enrollment game while also trying to come back from the pandemic hit, say Jenkins and Bevevino, they must ensure their programs are worth completing in order to improve recruitment and retention.

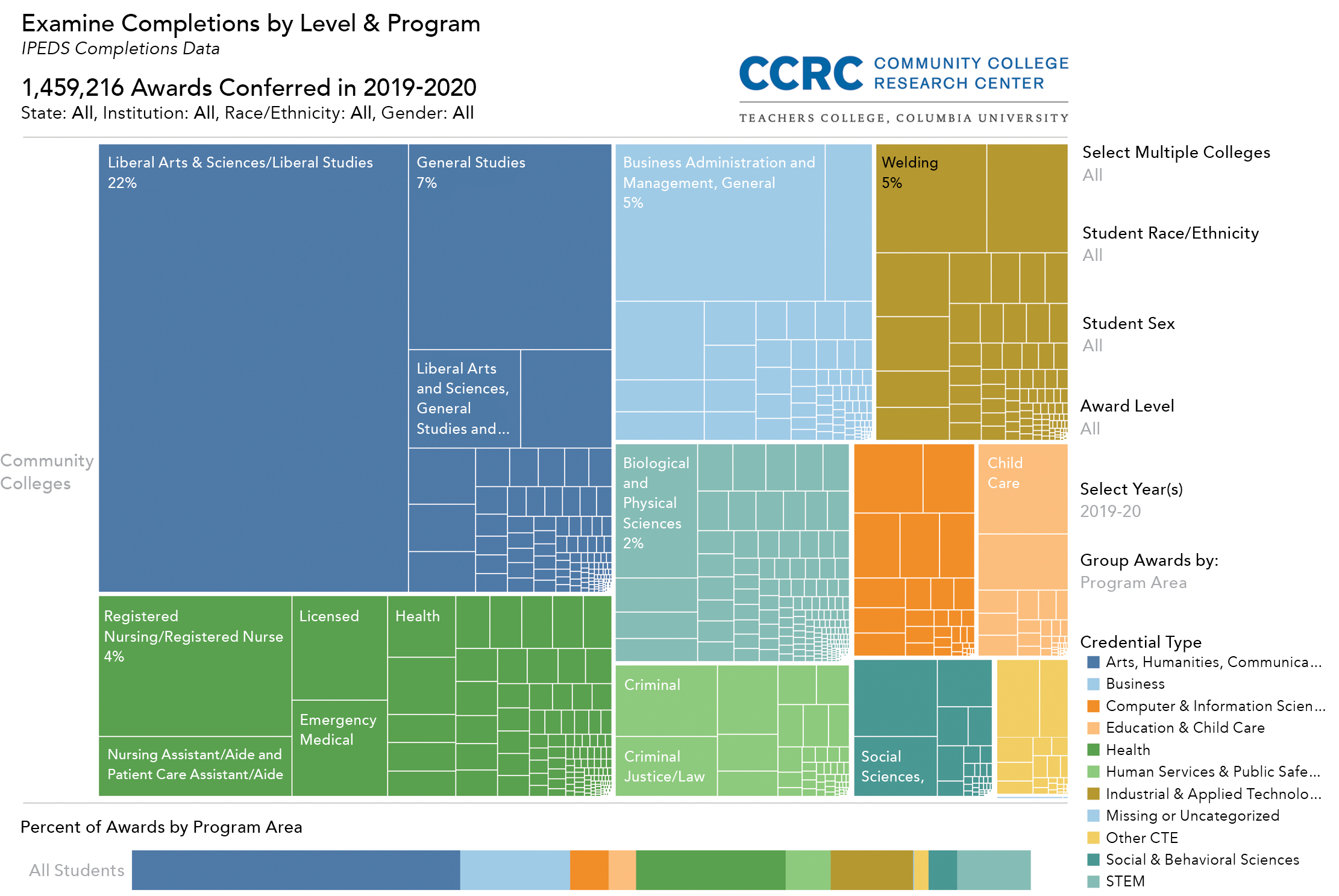

A data tool created by the CCRC allows users to examine individual college programs and post-graduation pay for institutions across the country using data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) with the National Center for Education Statistics. What quickly becomes apparent is how many students are enrolled in programs without strong earning potential. Registered nursing and industrial technology are the most rewarding fields but a large chunk of credentials are in liberal arts and general studies, which often have vague and/or low-paying job outcomes.

The competition for workers has brought tuition assistance into many offered compensation packages. “We think colleges have to be more aggressive working with those,” said Jenkins.

“We heard from employers that said some workers are taking advantage of that, but not many,” Bevevino said. “They wish more people would. Colleges need to make it clearer that using that will lead to higher wages. These students are pretty skeptical,” in part, added Jenkins, because their cousins and brothers and sisters have tried community college unlinked to such opportunities and have washed out of the system.

Transfer of credits into bachelor’s degree programs at 4-year colleges is a popular pathway, but a byzantine one. GAO analysis of Department of Education transfer and tuition data found that 22% of students’ earned credits are lost when transferring from a 2-year public college to a 4-year public college, some students having to take as many as 30 more credits than someone who entered the 4-year college directly. At one institution, Bevevino noted, there were 13 different administrative points where a student could get knocked out. “It’s pretty discouraging,” he said.

“When I talk to them, I want to cry,” Jenkins said of the transfer ordeal. “And I want to hire every single one of them.”

Unlocking Opportunity

Two- and 4-year colleges therefore have an important role to play in ensuring efficient and lossless transfer, they said. And community colleges in particular need to examine ROI across the range of career & technical education (CTE) programs, especially if they are mis-aligned with both hiring requirements and bachelor’s degree program requirements.

Bevevino and Jenkins were speaking to a room full of education journalists. But their suggestions of good questions to ask community colleges and “bad” answers to watch out for could be just as useful for any employer or student evaluating a community college. If you’re looking for programs to enable working adults to move up from low-paying jobs, but schedules, student services and advising are difficult to access and advisory boards “meet a couple times a year,” there may be cause for concern. Likewise if access to and success in high-value programs is limited to high school recruitment and comes with burdensome prerequisites; or if advisors there to keep students on track are themselves burdened with high caseloads of 300 or more students; or if a high proportion of enrollment is dual enrollment through high schools and not actively engaged with working adults.

Not that there aren’t bright spots. “There are lot of programs that help create stepping stones,” Bevevino said. At Valencia Community College in Florida, they admit they won’t get you to $45,000 in eight weeks. But they might get you to $15 or $17 an hour.”

Data show a large proportion of community college credential completions in areas such as General Studies and Liberal Arts that have lower-wage job outcomes.

Source: CCRC based on IPEDS data

“At Tulsa Community College, they are working with universities and other community groups for early childhood workers to get them social work degrees so some can move up,” Jenkins said. An accounting program at Zane State in Zanesville, Ohio, had low enrollment and retention so the school worked with employers to create an earn-and-learn structure that meant two days of classes and three days at work. “Both were losing out, but earn-and-learn structures can be powerful,” Jenkins said. Bevevino said community and technical colleges trying to get ahead of the game as a giant Intel fab and related investment come to Ohio are building in earn-and-learn early.

A stronger focus on ROI could help boost flagging community college enrollment.

Source: CCRC based on IPEDS data

“We also want to see new kinds of transfer programs,” he said, citing the ADVANCE program from Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) and George Mason University, where approximately 3,000 NOVA students transfer each year. “The whole time you know you are going to George Mason,” he said. “You are getting specific advising. You have access to parking for football games. Administrators thought it was odd we were excited about that program. We said, ‘That’s the point: You didn’t know it was any different.’ ”

To increase the focus on excellence and equity in post-completion outcomes, the Aspen Institute College Excellence Program and the CCRC are seeking out 10 institutions to comprise the inaugural Unlocking Opportunity Network, supported by Arnold Ventures, Ascendium and ECMC. They will work over three years on comprehensive reforms and three more years on evaluation in order to achieve one major goal: “thousands more community college students, including students of color and those from lower-income backgrounds, entering and completing programs that lead directly to jobs that pay a family-sustaining wage or to efficient and effective completion of a bachelor’s degree.”

Moreover, participating colleges “will commit to decreasing the number of students on paths that fail to confer strong post-graduation opportunity, including those who are undecided, in general education associate degree programs, and in CTE programs aligned to low-wage work.” Schools will be tasked with setting a family-sustaining “water line” wage standard and assessing program outcomes against it.

Bevevino said a number of schools are making moves in this area already. But “very few schools have asked that question. What is that family living wage water line? Can you see programs leading to that, and which don’t?”

“If they don’t have this orientation and intend to produce value, they’re not going to,” Jenkins said. “In fairness to community colleges, they’re not at a living wage either.”

“They need to decrease the number of students on paths that don’t confer strong post-graduation opportunity, whether labor or transfer,” said Bevevino. “This is a big shift. It could change faculty composition and the way you deliver programs. It is one of the first times we’ve brought schools together to create a research and learning community.”