Now that Russia has invaded the Ukraine and annexed the Crimea, many readers may call into question the idea that there can be such a thing as a good partnership with Russia,” says Glenn Williamson, author of “Inside Out: Building a Glass House in Russia,” As an expat brigade of Americans branched out across Central Europe in the 1990s, Williamson and others viewed Russia as a wide-open real estate market full of unlimited potential. “Thinking there not only could be, but have been, such partnerships might be seen as naïve at a time when we need to ‘stand up’ to the Russians,” he says.

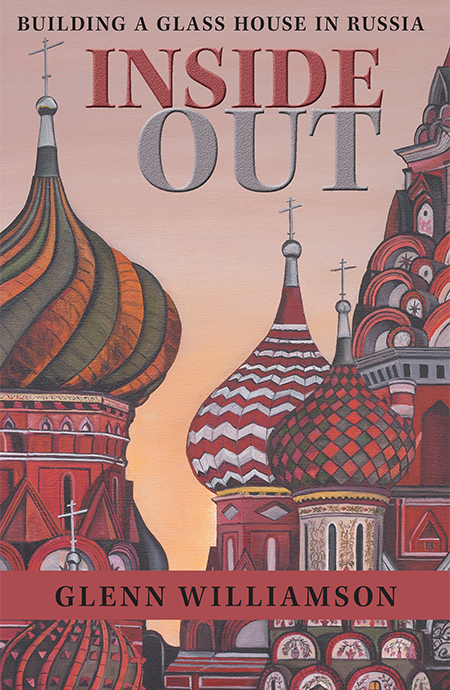

In his memoir, where the names have been changed but the story is real, Williamson takes readers into the reality of living and working in Russia. He narrates the anatomy of a real estate deal as he navigates local permits, international loans, and modern and medieval construction techniques on the path toward the award-winning development of St. Petersburg’s first modern Class A office building by a multinational team of Americans, Russians, Brits, Turks and Finns.

“At a time when Americans are once again perplexed with how to deal with Russians, this story shows what Americans and Russians are capable of — even under the worst of circumstances,” says Williamson.

By special arrangement with the author, below we present an excerpt from Williamson’s book, followed by his five tips for corporate real estate professionals working in Russia.

“Fifty Years of Nodortechnadzor” the banners proudly proclaimed. I could almost hear the people singing their eternal praise. Russians love anniversaries. Five, ten, fifteen, and especially fifty years were a big deal. I had seen the banners and read them, as I tried to read all of the various slogans left over from the Communist times, as well as announcements of coming events. One juxtaposition was classic. “Now greet Soviet Communism!” proclaimed one rooftop sign, while the matching sign on the adjacent building said, “If you smell gas, call 311.”

Kleptov and I were both still a little hung over as we walked down the sidewalk. The weekend before, Kleptov’s son had married his American fiancée. They had held a nice reception at a restaurant on Krasotsky Prospect, of course. The evening had gone on merrily and ended with two vivid images. One was of Kleptov, lying on his back and held in the air on a makeshift scaffolding created by the straining arms of several of his friends, so he could sign his initials in the ceiling with a cigarette lighter. This was clearly a local tradition at the restaurant. He was merely adding his initials to the others already there. The other image kept bothering me in the back of my mind. One of my staff had walked out of the reception with a bottle of vodka for the road. Not a good sign, I thought, when you leave a Russian wedding needing another drink.

Kleptov and I were on our way up the stairs to another dingy government office. We were responding to an official letter we had just received, informing us that, basically, we were in big trouble.

“Your boiler was imported without the proper authorization,” the official informed us. “You do not have a design for your boiler and your boiler has not been properly tested. It cannot be installed until it has been properly designed and tested. Vsyo. (That’s all).”

These conversations always scrambled my brain, because I would translate the words literally as they were spoken and then they never made any sense. To me a design was only needed to guide the construction of something that had not yet been built. Our boiler was not only manufactured, it had already been installed on the fourth floor of our building, underneath the fifth floor and the roof.

“Why do we need a design for something that is already built?” I asked.

“Because you don’t have one.”

“Why can’t we show you the plans that the Finns used to actually build it?”

“Because you need a Russian design.”

“We’ll translate it.”

“It’s not the same thing. A Russian design needs to be done by a Russian designer.”

Here we go, I thought. “Okay, which Russian designers are available for this task?”

“As a matter of fact, we have an affiliated private design firm that works with our public office and can complete this task.”

“Who runs this firm?” I asked.

“Me.”

I couldn’t even laugh. We were behind schedule and were pushing the Turks to catch up. Without an approved boiler we couldn’t do lots of things. Like heat the building. This meant that not only could we not open for business, we’d have to keep using portable heaters inside so that we wouldn’t ruin the finishes on the plaster and drywall. Summer ends quickly in St. Petersburg and we needed heat.

“So you’re telling me that if I hired your private firm, you could get me the approved design I need.”

“I can’t guarantee it.”

“Why not?” I asked.

“I can complete the design, but then it needs to be formally approved.”

“By you?”

“Yes.”

As a child I had seen a skit once on “The Carol Burnett Show” in which a tourist tries to appeal his speeding ticket in a small Southern town where the cop, judge, and mayor are all the same person. But in the skit, those three people all work in unison. This schizophrenic official was trying to maintain the independence of each role.

“What if we don’t redesign, or design po-russki, the boiler that is already built?” I asked.

“Then you have to have it tested, but you can’t test it in my city. It’s not safe, and once a boiler blew up and killed people. I have responsibility for the safety of the citizens of St. Petersburg and I won’t allow you to do this.”

How noble and inspiring this conversation was becoming.

“The boiler is built into the fourth floor of our five-floor building,” I said. “How can we test it outside of St. Petersburg?”

“You can cut a hole in the roof and get a helicopter to carry it to Finland, test it, and bring it back.” He said this with authority and seemed convinced of its logic.

“Maybe it could work,” Kleptov suggested.

Oh, my God, not now, I thought. This was worse than a bad TV comedy, and I knew Kleptov was already focusing on the deals he could make with the helicopter company. Absolutely insane.

“We cannot cut a hole in our roof,” I said, “and we cannot decide this question today. We need to speak with our contractor to see what can be done about the testing and the design.”

“Very well,” the official said. “I will wait to hear from you.”

Per the contract, our general contractor was responsible for securing all of the building permits required for the construction. We had fought like hell over this language, which called for one party to help as much as possible, but for the other party to ultimately be responsible for the result. Each party had eagerly tried to be the helper and promised the most diligent and far-reaching help possible, as long as the other party retained ultimate responsibility.

We had won the fight and they were responsible, so we met with them and tried to work out an intelligent solution to the boiler problem that would not impede the project.

Ultimately we did. The contractor was able to find a Russian designer, and the already built and installed boiler was designed and approved.

Fire, aim, ready.

1. Learn to speak Russian

One of the most fascinating things about Russia is that the language is so precise, but the world it describes is so chaotic. There are a lot of relationships to try to figure out, and if you can speak some Russian you will be way ahead. The hardest thing is to hear the side remarks that people make — those are often more telling than the translated speeches, but harder to follow. If you are only hearing the translated presentations, you will miss the tone and depth of feelings that will give you clues to judge where there may be opportunities and where there are simply dead ends.

2. Ignore things that don’t concern you

If you get distracted by all of the things going on around you, it will be that much harder to get anything done. You can be aware of things without getting involved, like a parent in the middle of a playground who doesn’t intervene in the game unless there is a danger. This approach also allows you to maintain your own individuality and integrity — no one expects you to have an opinion on everything you may notice or to get involved. It’s not polite, welcome or useful.

3. Keep your eyes on the prize

I used to tell our team, “We are not here to change the world, we just want to build a building.” That approach helps get the building built and is less threatening to others.

In the end, maybe in an incremental way, you can actually make a positive change. I was at a recent Georgetown University event where the former president of another university said that few people anywhere like change, but that many people will accept an experiment. I thought that comment was brilliant.

4. Respect the contributions of your foreign partners

Russia is a real place — not a fantasyland, but a place with real problems and real opportunities. I hope my book shows that all of the characters — Americans, Russians, Brits, Finns, Turks, Indians, etc. — are human. They have moments of greatness, and they make mistakes. From an educational point of view, I hope that readers can learn something about how developers try to take a dream and turn it into something you can touch and enjoy. As with any foreign country, respect the advice of local guides. They won’t always be right, but they have local insights and understanding that you wouldn’t appreciate as a foreigner. Some of these can be funny — we were advised not to host weddings — but others can be quite serious. A hotel developer in St. Petersburg didn’t take seriously enough objections to the potential dangers of extracting water from beneath his building during reconstruction. His own project was fine, but both buildings on either side cracked down the middle.

5. Recognize that Russia is a Land of Groups, not Individuals

Russian people live in a society made up of multiple small circles of friends. They can be wary of their fellow Russians outside of their known circles, so trying to build trust will take some time. Rather than trying to establish your company culture by hiring distinct individuals, you might consider working with Russian partners who would bring with them a group of people who already trust one another. Of course you will need to trust your partner. In our case, our main Russian partner brought all of the people for key categories of employees. Those employees were completely responsive to that partner in ways that we could never achieve in the short time period of working to develop our project.

The fall of the Berlin Wall, coupled with the collapse of the Chicago office market in the early 1990s, led Glenn Williamson to 10 years living and working overseas in Bulgaria, Russia and Poland as a banker, developer and advisor, followed by 10 more years running his own company, Amber Real Estate LLC, traveling back and forth between those emerging markets and his home in Washington, D.C. Today he teaches international real estate as an adjunct professor at Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies.