Rick Van Schoik is the Portfolio Director of the North American Research Partnership. This report is excerpted from “The US-Mexico Border Economy in Transition,” a new report from the Partnership that is further excerpted in the July 2015 issue of Site Selection. Read the full report for a full list of energy recommendations culled from the input of more than 1,000 attendees of four border-region competitiveness forums convened last year by the Partnership in San Diego, Rio Rico, El Paso and Laredo.

Energy is the lifeblood of economic development. As both a high value product in its own right and an essential input for every industry, energy production and supply are key factors in the competitiveness of any region.

The US-Mexico border region has traditionally been quite energy poor. The region imported large amounts of fuel and electric power from outside suppliers. Thankfully, sweeping changes are underway in the energy sector that have the potential to spark a new round of industrial development in the region comparable to the creation of the

maquiladora sector and the passage of NAFTA.

The border region is rich in renewable energy resources — particularly wind and solar.

States throughout the border region have made significant advances in developing these resources, but their potential is far from tapped out. More recently, the development of new drilling techniques has spurred a boom in oil and gas production from shale formations in south Texas. The pace of development is frenetic, and

the economy of the sub-region is being reshaped. Following the passage of energy reform in Mexico, there is great excitement over the potential for a similar revolution in northeastern Mexico, which enjoys much of the same promising geology as south Texas.

The two nations are closely linked in terms of their energy infrastructure and share both fuels and electrical power. For example, electricity flows both north and south in the Californias. In the spring and summer an excess of hydroelectric power in the northwest US affords cheaper power to Mexico to provide air conditioning and other cooling during the extraordinarily hot seasons in the greater Imperial and Mexicali Valley, while in the winter base load can be provided to the US side from large geothermal plants near the border in northern Baja California.

To take another example, when electricity supply in Texas is challenged by drought that limits hydro-electric generation or when demand peaks during cold snaps or heat waves, Texas utilities pull power north. As recently as October 2014, the Texas grid borrowed electrons from Mexico. Likewise the US has imported crude oil from Mexico and in return sends refined products that include cleaner grades of gasoline and low-sulfur diesel to Mexico. There is a much longer and richer history of U.S.-Mexico energy cooperation than many realize, but cross-border infrastructure limitations and a history of energy nationalism (in both countries) has put limits on the ability to take advantage of energy complementarities of the sort mentioned above.

Petroleum, Petrochemicals and Policy

Several major trends in supply are under way that translate into a major energy transition in North America as well as the border region. First, increased production means that the US will soon be a net exporter of many forms of energy and will soon send light crude to Mexico for the first time in addition to natural gas. Second, energy reform in Mexico is a reality, and private development will begin to produce both fuels and additional power within about a year.

According to some analyses, new foreign and domestic investment could potentially boost Mexico’s daily crude oil output to 5 million barrels per day, making Mexico the fourth largest producer in the world. If Mexico’s oil production undergoes this scale of change, the economic trajectory of the two nations and the border will change significantly.

The largest transitions that will occur in the United States relate to the revitalization of manufacturing due to affordable and easily accessible fuels for electricity generation and as inputs for petrochemical industries. In the United States, eliminating the ban

on petroleum exports (other than refined products and to certain free-trade agreement partner nations) could mean significant new revenues, while the process to enable liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities to export is similarly promising and already underway, including a proposed terminal in Corpus Christi, Texas, near the Eagle Ford shale formation.

However optimistic the potential energy transitions may seem, there are a number of challenges relating to US-Mexico energy interdependence. Policy cooperation between the two nations has been uneven. In 2001, the US Department of Energy and the

Mexican Secretariat of Energy (SENER) worked with Natural Resources Canada through the North American Energy Working Group, but the group has not met for several years. In 2011 the US and Mexico launched the Presidents’ Cross-border Electricity Task Force with the goal of promoting regional renewable energy markets between the two countries. The parties met but never named official representatives, obviously a prerequisite of a successful task force.

Similar frustration accompanies the Bilateral Framework on Clean Energy and Climate Change, which only met a handful of times. However, the two nations did successfully

negotiate an agreement to jointly develop the deepwater reserves in the Gulf of Mexico. The US-Mexico Transboundary Hydrocarbons Agreement was passed by the US Congress in 2013. As in broader economic integration efforts, individual agreements

seem to have been more successful than efforts to institutionalize cooperation.

Reform

While reform of Mexico’s energy sector, was unimaginable for generations for a host of historical and political reasons, Mexico’s Congress changed the energy landscape dramatically in 2013 and 2014 with legislation opening up the sector to private investment in a number of key areas.

Secondary laws fleshing out the 2013 constitutional changes were passed in the summer of 2014 and will enable the petroleum, natural gas, and electricity sectors to modernize and engage private investment upstream (exploration, development, and production), mid-stream (refining, processing, conveyance, and storage), and downstream (distribution, sales, and retailing). New hydrocarbon and climate commissions have been institutionalized, and two rounds of bidding on projects have already begun, with more expected. Essentially all components of energy provision allow private engagement and competition.

What this means for the border region, where much of that transition will occur, is dramatic. Environmental protection has been addressed under reform as well. Private electricity [generators], also known as Independent Power Producers or IPPs, are mandated to meet new efficiency and pollution standards. This complements Mexico’s already existing national renewable portfolio standard (RPS), strengthening the framework for clean energy generation in the border region.

Natural Gas

Because of a boom in US shale gas production and high demand in Mexico, natural gas will fuel the energy transition in the near term. New drilling technologies have increased the production and affordability of shale gas and shale oil. In early 2015, oil prices were

approximately $55 a barrel and natural gas prices just above $3 per million BTUs at Henry Hub, Louisiana.

The Eagle Ford Consortium, which was represented at the recent Regional Economic Competitiveness Forum in Laredo, Texas, reports an almost $90-billion economic impact, the creation of 128,000 jobs and over $2 billion in revenues to local and state

governments as a result of shale oil and gas development in the area.

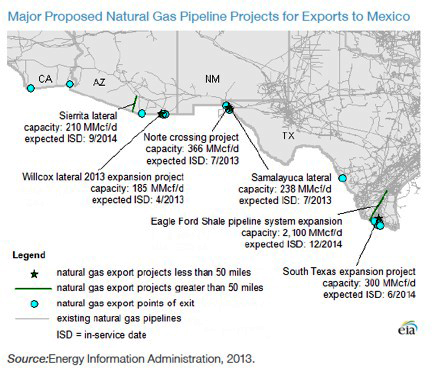

Growth on the Mexican side is expected to follow as technology and equipment is exported and energy reform is implemented. The United States has 1.5 million miles of natural gas transportation and distribution lines. Mexico has less than a tenth of that, and a shortage of cross-border connections in particular has kept the price of gas much higher in Mexico than in the United States.

Mexico’s Energy Secretariat projects natural gas demand to increase 3.6 percent per year from 2012 to 2028, but domestic production to rise just 1.6 percent per year. The Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Coahuila, and possibly Chihuahua all have important natural gas reserves that, as a result of energy reform, may see significant

development in the coming years.

Nonetheless, to keep up with rising demand and to lower electricity costs, Mexico will need to important large amounts of natural gas from the United States. This will require the construction of new cross-border and domestic pipelines, and, indeed, Mexico plans to double pipeline capacity over the next decade. To accomplish this, Mexico will need foreign direct investment (FDI) and permits from both presidents to allow the cross-border connections.

The Impact of Falling Energy Prices

With crude oil prices less than half what they were in mid-2014 and expected to stay low, although perhaps not as low as they currently are, for some time, border states should expect significant changes. Major energy producers will feel a pinch as lower prices force energy companies to tighten their belts. The long-term viability of shale oil and gas projects is not in question, but the speed of their development, in both the United States and Mexico, will be significantly slowed as a result of dramatically lower oil prices.

The Mexican federal government, with its large reliance on oil revenue to finance its annual budget, will also feel pressure. Because of their reliance on federal contributions, these budgetary impacts will be extended to Mexican state governments. As a result of falling oil prices and other economic factors, the Mexican peso has weakened vis-à-vis the dollar. This makes imports more expensive for Mexican consumers, companies, and governments, but it also makes the country more attractive for foreign investors in both energy and manufacturing industries, who can get more out of their dollar-denominated investments locally and, in the case of manufacturing, can also take advantage of more competitive export prices.

Finally, the boon to manufacturers is further extended because of decreased shipping and energy costs. In short, cross-border trade should rise on the back of better prices, but energy industry growth and associated government revenue will slow down.

Job and Career Creation

Energy development offers significant job creation opportunities for both the United States and Mexico. Certain skilled positions, including welders, truck drivers, and several types of engineers, will be in particularly high demand. As a consequence, the

border communities that do the best job of building the relevant educational and skill base will best be able to take advantage of the economic development opportunities the energy industry offers.

The regional nature of supply chains in the United States and Mexico means that our interconnected industries build products together that we sell to the rest of the world. Components built for the production of energy are no exception. For example, a wind farm may have blades built in Ciudad Juárez and a generator manufactured in the US atop a tower constructed in either nation.

A recent McKinsey report argues that 1.7 million permanent jobs will be created by the shale oil and gas boom followed by 3.9 million jobs in manufacturing afforded by cheaper and plentiful energy. The Federal Reserve estimates that for every 10 jobs created in a maquiladora in Mexico somewhere between two and six jobs were

created on the US side. Interviews with those in the energy sector indicate similar interdependence of energy clusters on both sides.

Energy Industry Security

While security at ports of entry remains a concern, another security challenge has emerged in the energy sector as transnational crime organizations (TCOs) have become engaged in energy-related crime. These groups steal oil, damage pipelines,

and otherwise disrupt energy flows. Both property and lives are threatened as these TCOs capture wells and trucks, as well as at times kidnapping personnel. If unaddressed, security concerns in northeastern Mexico could hamper energy development and the competitiveness gains that accompany it. The New York Times reported on October 29, 2014, that TCOs have stolen $1.15 billion from pipelines, a perennial problem for PEMEX. Private industry is carefully watching how governments at all levels respond to their security concerns.

A North American energy market is important for both national and continental security and a better quality of life for all. The main reason we should celebrate our newfound North American energy clout is its ability to create and sustain good jobs in all three nations. With proper human capital development and a strong planning and regulatory process to protect the natural environment, the benefits can be broad-based and sustainable.

Energy interdependence and (through the leveraging of complementarities) energy security begins with having enough power and pipeline infrastructure to move electrons and hydrocarbons and perhaps even captured carbon across national borders. The US, strategically positioned between Canada and Mexico, is a major winner, as it is able to import and export to friendly neighboring nations and across land borders instead of

engaging continually in the expensive practice of loading, moving, and unloading ships.

In Mexico, energy reform will spur oil exploration and development, both in old fields where enhanced recovery techniques and technological investment will allow extraction from deeper and more complex known reserves. In addition, new oil and gas resources will become available as private energy companies take advantage of the new legal framework.

Finally, the electricity market in Mexico and the United States will be transformed as new conventional and renewable sources come on line. Additionally, more cross-border energy trade should be anticipated and prepared for.