This year marks the 25th anniversary of the economic development strategy known as economic gardening, and the 90th anniversary of the National League of Cities (NLC). Christiana McFarland, research director at the NLC, offers insights from the organization’s years of economic development experience.

Economic gardening is an economic development approach with a fine attention to smaller companies with growth potential. This “grow from within” development strategy started in Littleton, Colo., in 1989 after the relocation of a major employer devastated the local economy. Precisely because of this harsh history, economic gardening became associated with small businesses, specifically eschewing economic recruitment or a focus on larger employers.

According to Chris Gibbons, director of business/industry affairs for the City of Littleton and co-creator of economic gardening, “The relocation of manufacturing plants offshore and the general decline of economic health in parts of the country have reduced the effectiveness of traditional economic ‘hunting.’ ” For these reasons, economic gardening in its purest form has been adopted in smaller, more rural and harder-hit areas of the country.

Out of those start-up seedlings has come a harvest of second-stage businesses – companies that have moved past the start-up phase of development but are not yet fully mature. They have a proven product and a market for their goods or services often reaching beyond the local area, bringing dollars into the community, and generating a substantial economic impact.

As the outsized impact of second-stage businesses became more apparent, as cities came to realize that typical small business programs didn’t meet the needs of these unique businesses, and with a desire to strengthen the broader business ecosystem, cities across the country have therefore adapted economic gardening to their local circumstances. What has evolved is a second-stage strategy that leverages larger employers in meaningful ways to accelerate smaller businesses.

Where to Connect?

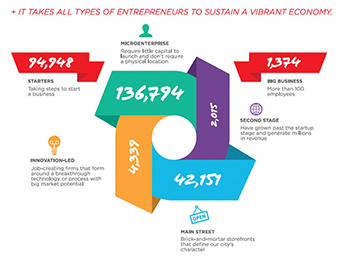

According to the Edward Lowe Foundation, between 1995 and 2012, second-stage companies represented 11.6 percent of establishments, but 33.9 percent of jobs. Employee numbers and revenue ranges vary by industry, but the population of firms with 10 to 100 employees and/or $750,000 to $50 million in receipts includes the vast majority of second-stage companies.

“Second-stagers now face more strategic issues as they strive to gain a stronger foothold in the market and win more customers,” says the foundation. “Second-stagers wrestle with refining core strategy, adapting to industry changes, expanding their markets, building a management team and embracing new leadership roles.”

According to the US Small Business Administration, economic gardening addresses these unique needs by providing infrastructure, connectivity and market intelligence.

In Kansas City, Mo., KCSourceLink (

www.kcsourcelink.com

) connects small businesses to a network of more than 200 nonprofit resource organizations in the region that provide business-building services.

“In the 11 years we’ve been working in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, we’ve determined that second-stage companies are a key segment, creating jobs and stability in the community,” says Maria Meyers, director of the UMKC Innovation Center and KCSourceLink founder. “Resource partner organizations in the network – such as the Helzberg Entrepreneurial Mentoring Program, the Small Business and Technology Development Center and the World Trade Center – provide second-stage companies with critical connections to larger corporations, mentoring and market opportunities.”

From Vacant to Vibrant

A key trait of second-stage companies is their readiness to grow, both physically and with new market reach. Acceleration of growth firms has actually become an attraction strategy for some suburban communities located outside of larger innovation hubs such as Boston, Austin, Cleveland and Kansas City.

These communities may not have a high density of traditional start-up supports, but can offer value-add to companies seeking to expand, such as affordable wet-lab space.

In turn, some innovation hubs are focusing not only on the growth of start-up and second-stage companies, but on retaining them as well. In order to do that, these cities need to provide both the physical space and the market opportunities for them to continue to grow from within -and this where the opportunities lie to engage larger businesses.

The City of Cleveland’s rallying point for second-stage companies is actually its anchor strategy, an economic development approach that leverages the economic power of major employers such as hospitals and universities to build wealth in neighborhoods and grow other industries and businesses.

In Cleveland, anchor institutions were incubating some great start-ups, but as they reached second stage, they left for the suburbs, or were purchased and moved to other locations. In an effort to further capture value from their anchor strategy, the City of Cleveland partnered with local developer Fred Geis to create space for second-stage companies. This “post incubator space” came with all the amenities these growth companies seek, as well as incentives from the city and continued engagement with hospitals and universities.

“The three buildings in the Midtown Tech Center have allowed us to capitalize on our Anchor Strategy, attracting companies like Cleveland Heart Lab that have grown from 15 jobs when they exited the incubator to over 115 high-paying technical jobs now,” says Tracey Nichols, director of economic development for the City of Cleveland. “These former vacant properties have brought 389 jobs to the area since 2012.”

Although economic gardening arose as the antithesis to larger employers, the approach as a solo strategy disconnected from retention/attraction efforts is rare. More often, as in Cleveland, economic gardening has evolved as an integral part of a broader economic development portfolio, leading to a more strengthened and supportive business ecosystem.

For more, visit www.nlc.org.