There is no shortage of opportunity at the more than 4,000 free zones dotting the globe. There is, however, a paucity of intelligent insights into their workings, effectiveness and challenges.

Here we present excerpts of recent analyses from organizations with no shortage of acute expertise. First up: Douglas Zhihua Zeng, senior economist at the Financial and Private Sector Development Department of the Africa Region, World Bank. His analysis originally was published earlier this year at the World Bank’s Trade Post website.

In the late 1950s, a group of businessmen and politicians on the outskirts of a small town in western Ireland realized their local airport was in jeopardy of losing its international flights. Knowing how important transit passengers and the airlines were to their economy, a proposal for a special industrial area near the airport was submitted and approved, marking the inception of the world’s first modern free trade zone in Shannon, Ireland.

Today, the concept has gone global with an estimated 4,300 various types of zones worldwide. All across the world, we have seen countries exploring and seizing the potential of these industrial zones — often also called industrial parks or special economic zones. In East Asia, you can point to the experiences of China, Singapore, Malaysia, the Republic of Korea and Vietnam. In Central America, we have those of the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, and Honduras. In the Middle East and North Africa, the United Arab Emirates and Jordan have also created zones. In Sub-Sahara Africa, Mauritius first set up an export processing zone all the way back in the 1970s, and today, countries across the region continue to experiment with modern industrial zone regimes.

“China’s first special economic zone — Shenzhen — is now one of its most developed and innovative cities.”

The concept of the industrial zone is gaining more acceptance globally. The appeal lies in these zones’ ability to catalyze economic development and structural transformation. The experience of industrial zones in emerging economies has proven that, if implemented successfully, they can help to generate employment, foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign exchange earnings, exports, and government revenues.

While results have been mixed in certain countries, in the more successful cases, industrial zones have also helped to facilitate skills upgrading, technology transfer, adoption of modern management practices, economic diversification, and cluster formation. In some countries, zones were even used to test economic reforms and new policies and approaches. By creating a demonstration effect, once successful, these reforms were replicated nationwide. This approach is inseparable from China’s remarkable economic transformation over the last three decades. China’s first special economic zone — Shenzhen — is now one of its most developed and innovative cities, with a population of around 12 million.

How are industrial zones able to achieve such effects? The main reason is that these instruments can help to overcome the binding constraints of business development, such as rigid and constraining regulatory regimes, poor infrastructure, and inadequate trade logistics. They do so by creating a more conducive business environment in a geographically limited area. This can be achieved through a more liberal legal and regulatory framework, efficient public services, and better infrastructure within the zone, including better roads, power, water, and wastewater treatment. Some newer-generation zones are even becoming the drivers of green development and eco-industrial cities.

Developing countries often cannot create the business environment or build out enabling infrastructure nationwide all at once, due to limited resources and implementation capacity. They often also have limited political capital to defend policies and reforms against vested interest groups and political opposition. This makes targeted interventions or a pilot approach necessary, especially at the initial stages. However, it’s important to note that industrial zones should be used to address market failures or binding constraints that cannot be addressed through other options. If the constraints can be addressed through countrywide reforms, sector-wide incentives, or universal approaches, then zones might not be necessary.

Creating an industrial zone is a very expensive undertaking and involves very careful and skilled planning, design, and management. It should not be taken lightly. Unlike early days when most zones were developed by government, today more and more zones are developed through public-private partnerships (PPP), with increasing participation from the private sector. In such cases, the functions of the public sector typically include implementation of a transparent and clear regulatory framework, provision of land and efficient public services, financing of basic infrastructure, and oversight of private developers or operators. The private sector partner(s), on the other hand, will be responsible for zone development and operation, provision of certain on-site infrastructure, and services, like asset management, global outreach, and investor relations.

To be clear, industrial zones are not a panacea. They may fail for various reasons. But successful zones often possess the following key characteristics:

- a robust legal and regulation framework and strong institutions, including effective one-stop-shop services

- strong government support as part of the national development strategy

- a prototype design for broader national reforms

- a strategic location with sound infrastructure

- strong commercial viability and significant economic and social returns.

Record Highs in the United States

Data from zones in the US is available from the annual report to Congress from the US Foreign-Trade Zones Board, published in August 2015. The value of exports from US Foreign-Trade Zones (FTZs) increased by 24.8 percent in 2014, to a record-high $99.2 billion in merchandise exported — a threefold growth of FTZ exports in the five years since 2009. FTZ employment also set a new record in 2014, with 420,000 jobs reported, representing a 7.7-percent increase over 2013 — far outpacing the overall US employment growth of 1.9 percent.

“The FTZ Board’s latest report confirms that the program continues to be a vital component of America’s trade policy,” said Daniel Griswold, president of the National Association of Foreign-Trade Zones, a trade association of more than 600 members. “The competitive advantage for companies operating in an FTZ has enabled them to boost their exports and employment to record levels, continuing their strong contribution to America’s economic recovery.”

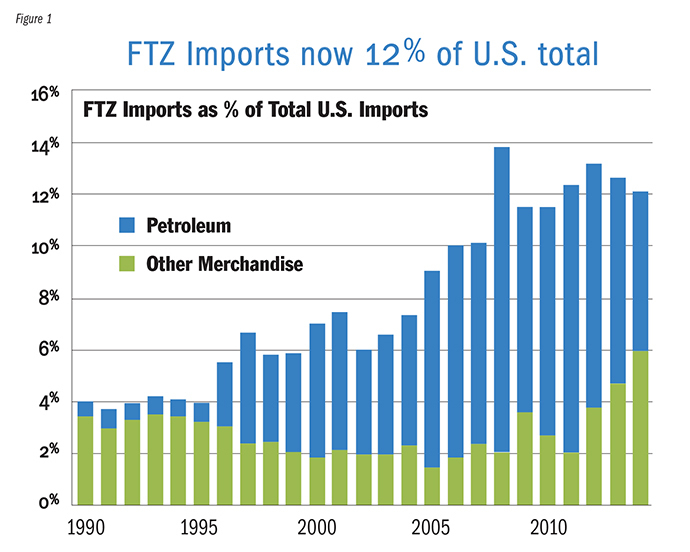

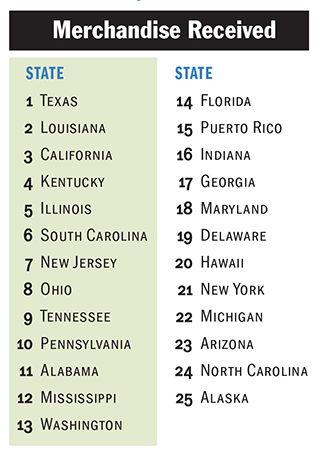

Foreign-status inputs to FTZs totaled $288.3 billion in 2014, accounting for 12.1 percent of all US goods imports. FTZ imports have tripled as a share of US imports over the past two decades. There were 179 active FTZs during 2014, with a total of 311 active production operations; 2,700 firms used FTZs during the year. The FTZ Board processed 57 applications for new or expanded production authority in 2014, and reorganized 18 zones under the alternative site framework (ASF).

“Foreign-trade zones continue to be hubs of manufacturing activity where domestic and foreign-sourced inputs are combined by American workers on US soil to produce value-added final products for export and domestic consumption,” said Griswold. “Key US industries depend on the FTZ program to remain competitive. But we can do even better. US Customs should take every step to fully integrate FTZs into the Automated Commercial Environment as soon as possible to ensure that US FTZ manufacturing operations can take full advantage of global supply chains.”

Free Does Not Mean a Free-For-All

The International Chamber of Commerce’s Business Action to Stop Counterfeiting and Piracy coalition recently released “Controlling the Zone: Balancing facilitation and control to combat illicit trade in the world’s Free Trade Zones.” Here are its key recommendations:

- Review and implement national IPR legislation and include language that makes legislation applicable to all goods in the national territory, in all Customs regimes, including transit, in-transit, and free-zone regimes. Further state that the discovery of prohibited goods may result in civil and criminal penalties.

- Empower Customs with authority over goods in all territories, including FTZs, SEZs and free ports.

- Clarify that FTZs (or SEZs or freeports, etc.) are under the jurisdiction of the national Customs authority; that national Customs has unrestricted rights to enter and observe operation, to audit the books and records of companies in the zone, and to validate goods status and conformance with tariff and nontariff measures under the national Customs mandate.

- Grant Customs ex-officio power to detain goods suspected of infringing on IPR, including goods in FTZs, SEZs, free ports, and the like.

- Enable cooperation between national Customs authorities and the special authorities of FTZs or free ports to ensure efficient enforcement of anti- counterfeiting criminal and civil laws to regulate the offenses of trafficking in counterfeit goods.

- Include provisions to simplify the process for notifying trademark holders of infringement and enable them to initiate enforcement action; institute a simple procedure for destroying infringing goods from changing destination to evade enforcement.