When Spirit AeroSystems a decade ago pledged to invest more than half a billion dollars and create hundreds of jobs at the North Carolina Global Transpark in Kinston in the rural eastern part of the state, stakeholders including the North Carolina Community College System Customized Training Program and Lenoir Community College sprang into action on a customized hiring and training program.

They created the Spirit AeroSystems Global Composite Center of Excellence, screened applicants and ramped up curriculum for an aerospace manufacturing readiness program, where students not only gained immediately applicable job skills but earned credit toward a two-year aerostructures degree.

The best part, says Tamar Jacoby, founder and president of Opportunity America, is the training resources came together with specific intentions instead of a blank canvas.

“When you want to move to North Carolina, the state doesn’t say, ‘Here’s a big pile of money for training,’ ” she observes. Instead, the state commits to building up the capacity of the community college, the company gets the workers it wants and all parties win. “Spirit paired up with this little college in the middle of nowhere,” she says, “and five years later you have this amazing training capacity” because the state didn’t write a blank check.

Opportunity America is a Washington-based nonprofit promoting economic mobility — work, skills, careers, ownership and entrepreneurship for poor and working Americans. In September 2021, in concert with Lumina Foundation and Wilder Research, the organization published “The Indispensable Institution: Taking the Measure of Community College Workforce Education,” a report derived from a year-long national survey of community college educators that yielded responses to at least one of the questions from more than 600 leaders at two-year schools.

Among principal findings: Fifty-four percent of the students at the community colleges that responded to the survey are enrolled in job-focused programs. An estimated 3.7 million students are enrolled in noncredit programs — learners more interested in skills than academic credentials who are not included in federal education data and often invisible to policymakers. Most urgent from a policy standpoint: Noncredit workforce education is ineligible for federal financial aid, leaving students and employers to carry the lion’s share of the burden — 53% of the cost nationwide and more than 80% in some states.

Here we present excerpts of the report.

Are Colleges Embracing a Workforce Mission?

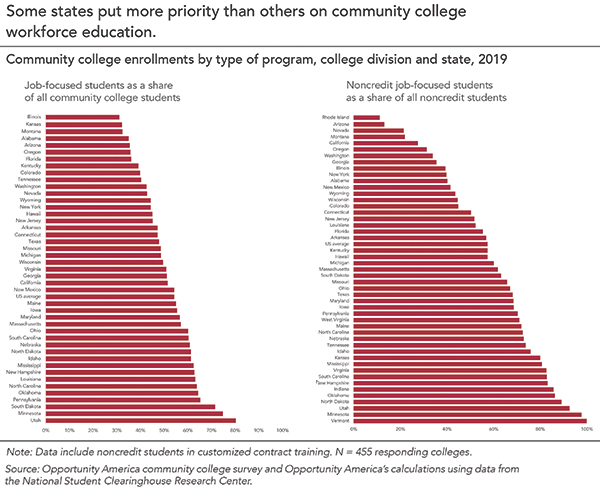

National averages suggest that most community colleges make a priority of preparing learners for the world of work. Individual college results tell a more nuanced story. Some institutions are focused single-mindedly on readying students for the workforce. Others devote most of their attention to preparing students to transfer to four-year institutions. Some succeed in doing both, balancing two critical and complementary missions. Still others try to be all things to all learners and end up doing nothing well.

Similarly, at the state level, our survey found dramatic differences among states. In some states — Minnesota, Pennsylvania and Utah top the list — more than two-thirds of community college students, credit and noncredit, are enrolled in job-focused programs. In other states — including Kansas, Illinois and Montana — the share is less than one-third. In nine otherwise very different states, including New Hampshire, Utah and South Carolina, more than 80% of noncredit students are pursuing job-focused education. In other states — Arizona and Nevada the share is roughly 20% or less.

But the challenge facing community colleges does not end there. Not all workforce skills are created equal. What matters — what learners need — are skills in demand in the local labor market, valued by employers and required in real time for open jobs.

Community colleges have three primary tools to stay abreast of shifting in-demand skills: employer partnerships, noncredit education and competency-based industry certifications. Our survey sought to assess how well they are using each of these tools.

Employer Partnerships

Many community college administrators boast about their ability to engage employers, and when asked how many partners they have, they often offer impressive estimates.

The average small college — fewer than 1,000 students — reports 65 employer partners. The average number for large institutions — more than 20,000 students — is 541 relationships. But without more concrete, descriptive detail, these numbers may be misleading.

Our questionnaire attempted to dig deeper by asking responding colleges to sort their employer relationships into four broad categories: employer sponsors, employer advisers, employer partner/customers and contract training clients. Colleges reported that on average one-quarter of their employer partners offered customized contract training — usually a fairly intensive collaboration, albeit on upskilling open only to incumbent workers chosen by the sponsoring firm.

Asked about collaborating with employers to offer programs open to students enrolled at the college, educators reported that on average 14% of the employers they worked with were sponsors, 46% engaged as advisers and as many as 37% were full-fledged partner/customers.

"An estimated 3.7 million students are enrolled in noncredit programs — learners more interested in skills than academic credentials who are not included in federal education data and often invisible to policymakers."

Perhaps the most telling question we asked colleges about their industry partnerships focused on work-based learning — internships, apprenticeships, cooperative education and other on-the-job experience. Encouragingly, nationwide, colleges report that on average 36% of their employer partners provide some kind of on-the-job work experience, and in some states, nearly two-thirds offer work-based learning opportunities.

Noncredit Education

A second essential tool for maximizing any community college’s labor market alignment is the noncredit continuing education division — a unit ideally positioned to connect instructors and administrators with the local labor market. How many colleges make the most of their noncredit divisions in this way? Our study looked at three telling indicators: noncredit fields of study, noncredit program length and the intensity of noncredit employer engagement.

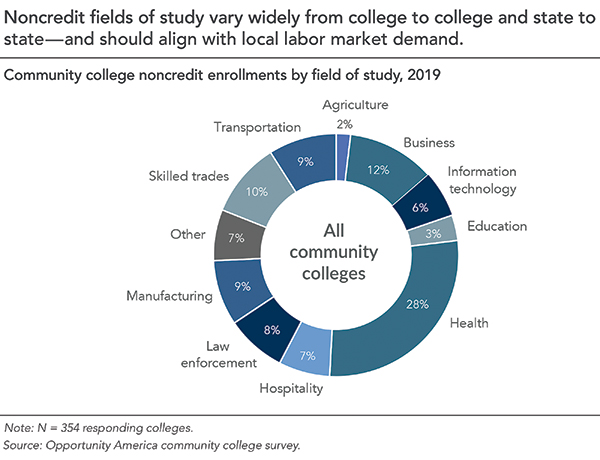

Field of Study: Nationwide, health care predominates by a large margin. Some 30% of noncredit workforce students are enrolled in programs designed to prepare them for health care jobs, with most of the next biggest concentrations — in programs targeting business, manufacturing, transportation and the skilled trades — each logging in at close to 10%. The critical question for educators: Does the mix of programs they offer match labor market demand in their region?

In some cases, it does. Consider the states with the largest share of noncredit programs in manufacturing: Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi and Ohio. All five also rank among the top manufacturing states nationwide by employment. Other states use their noncredit workforce programs even more strategically. In Oklahoma, for example, where the aerospace and defense industries touch roughly one-quarter of all jobs, 22% of noncredit workforce students study aerospace and aviation.

Program Duration: Unlike on the credit side of the college, where virtually all courses are the same length — a 15-week semester — noncredit instructors can vary the duration of the programs they offer. Less complex skills require less training, allowing for shorter programs. And in theory, market discipline, whether from students in a hurry to get jobs or employers ramping up to meet customer demand, should keep programs just the right length — no longer than it takes to acquire essential skills.

In fact, our survey found dramatic variation across noncredit workforce programs, with nearly two-thirds — 63% — measuring fewer than 100 clock hours and just 8% requiring more than 600 hours of instruction. This could be a good sign — evidence of encouraging labor market alignment.

But it’s also of some concern. Under current law, only students enrolled in noncredit programs longer than 600 hours are eligible for federal financial aid. And a popular reform proposal to lower that threshold — the Jumpstart Our Businesses by Supporting Students (JOBS) Act — would provide only for programs longer than 150 hours, leaving out a full 76% of noncredit workforce course offerings.

Noncredit employer partnerships: Is the conventional wisdom true — do noncredit instructors and administrators have closer, more intensive ties to employers than their peers on the credit side of the college? And do they use these relationships shrewdly to ensure that students are learning skills with value in the local labor market?

Our data suggest that they may. Asked what means they use to ensure the quality and labor market relevance of their noncredit workforce programs, the administrators who responded to our survey ranked input from local employers as their No. 1 tool — a full 92% say they design and revise programs on the basis of industry input.

Industry Certifications

Unlike traditional academic credentials, which signal that students have attended and completed a course of study, industry certifications signal what learners know and what job-related tasks they can perform — occupation-specific knowledge and skills measured by tests developed by employers.

What share of credit and noncredit college programs prepare students for certification assessments? Our findings suggest that the most telling threshold for both the credit and noncredit division is one-third of programs: Do more than one-third of the programs at the college prepare learners to sit for certification tests? Some 29% of the colleges in our sample said their credit programs met this threshold. For noncredit programs, the figure was 32%.

Looking just at the noncredit side and at learners rather than programs, the colleges in our sample report that on average 25% of workforce students earn industry certifications, and another 11% — perhaps overlapping, perhaps not — earn some other type of third-party credential such as a government certification or licensure.

The challenge for public policy: how to encourage and incentivize colleges to make better use of all these tools — employer engagement, noncredit workforce programs and industry certifications. Policymakers can help by providing information and advice — state lists of certifications valued by employers, for example, or more detailed taxonomies of employer collaboration that colleges can use to assess their relationships.

But ultimately the best leverage is likely to be tangible incentives: developing performance metrics, holding colleges accountable and rewarding institutions that succeed in keeping abreast of the local labor market.

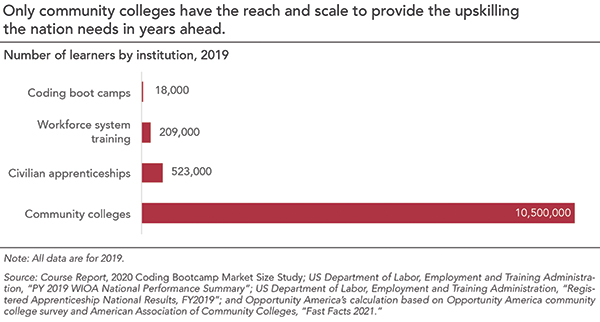

Demand for workforce education is poised to explode in years ahead as automation and business restructuring transform the labor market. Some workers who need to change jobs will make do without reskilling. Others may be lucky — their new employer will train them. But many if not most will need to reboot on their own, and many will look to their local community college — particularly, if they’re in a hurry, to its noncredit workforce education division.

Public two-year institutions are poised to step up, but there is much work to be done to make community college workforce education all it can be for learners, employers and the regional economy.

Tamar Jacoby is president and CEO of Opportunity America, a Washington-based nonprofit working to promote economic mobility — work, skills, careers, ownership and entrepreneurship for poor and working Americans. For more information, visit opportunityamericaonline.org.