The US metropolitan areas tallying the most corporate facility investment projects in 2016 aren’t just competitive nationally — they’re succeeding on a global scale.

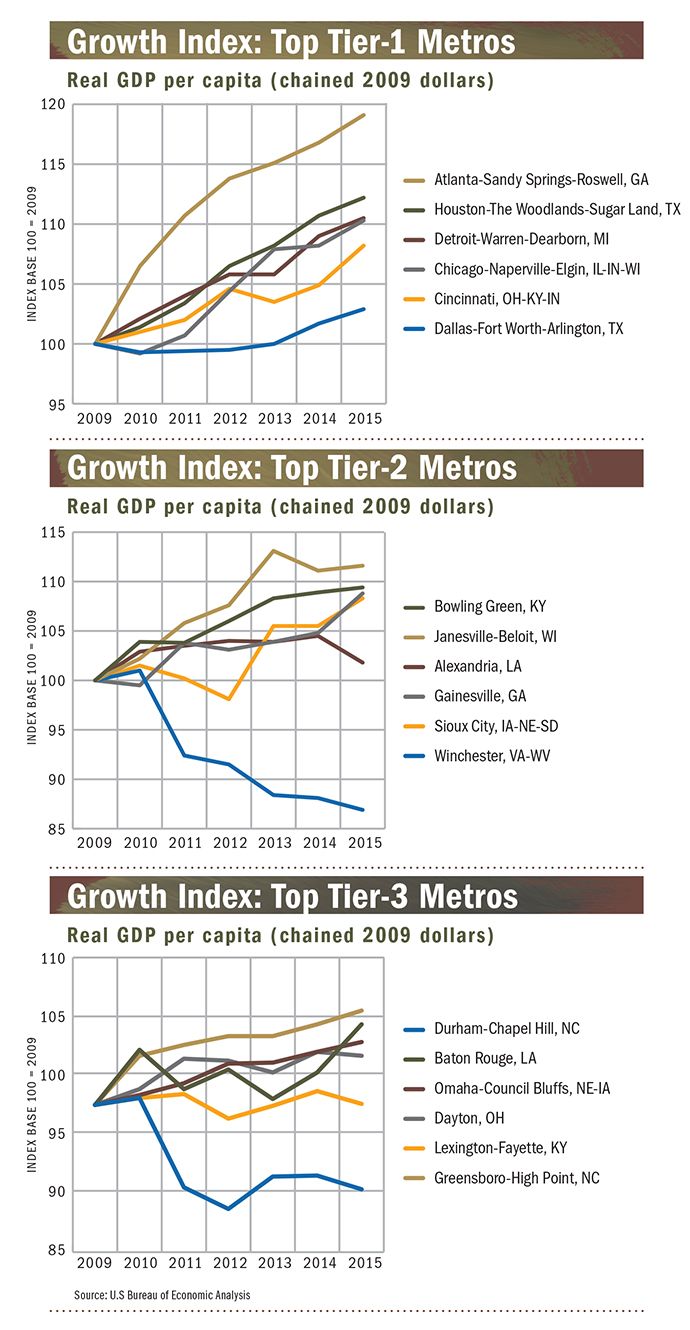

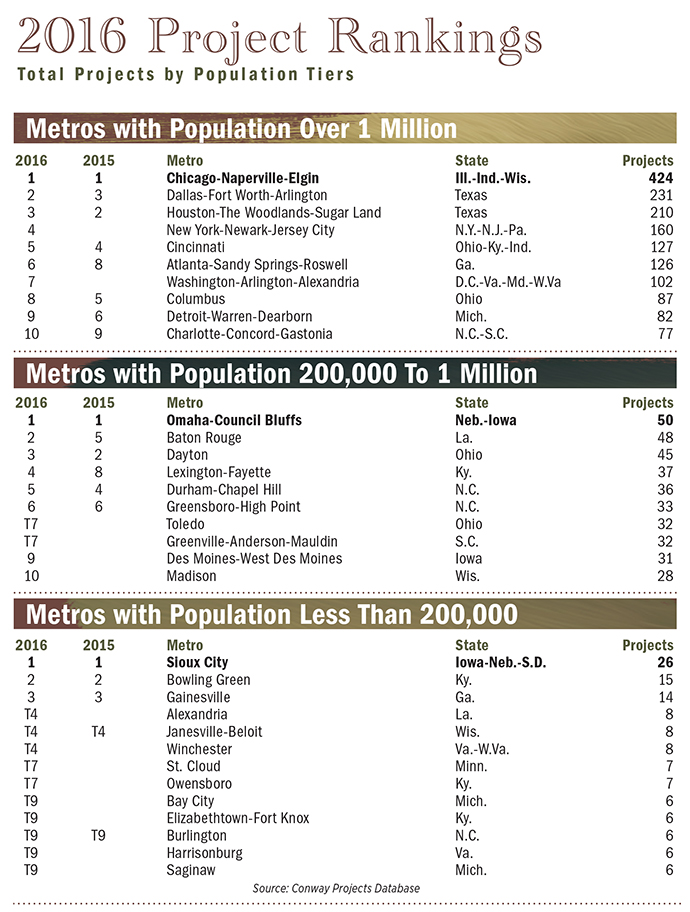

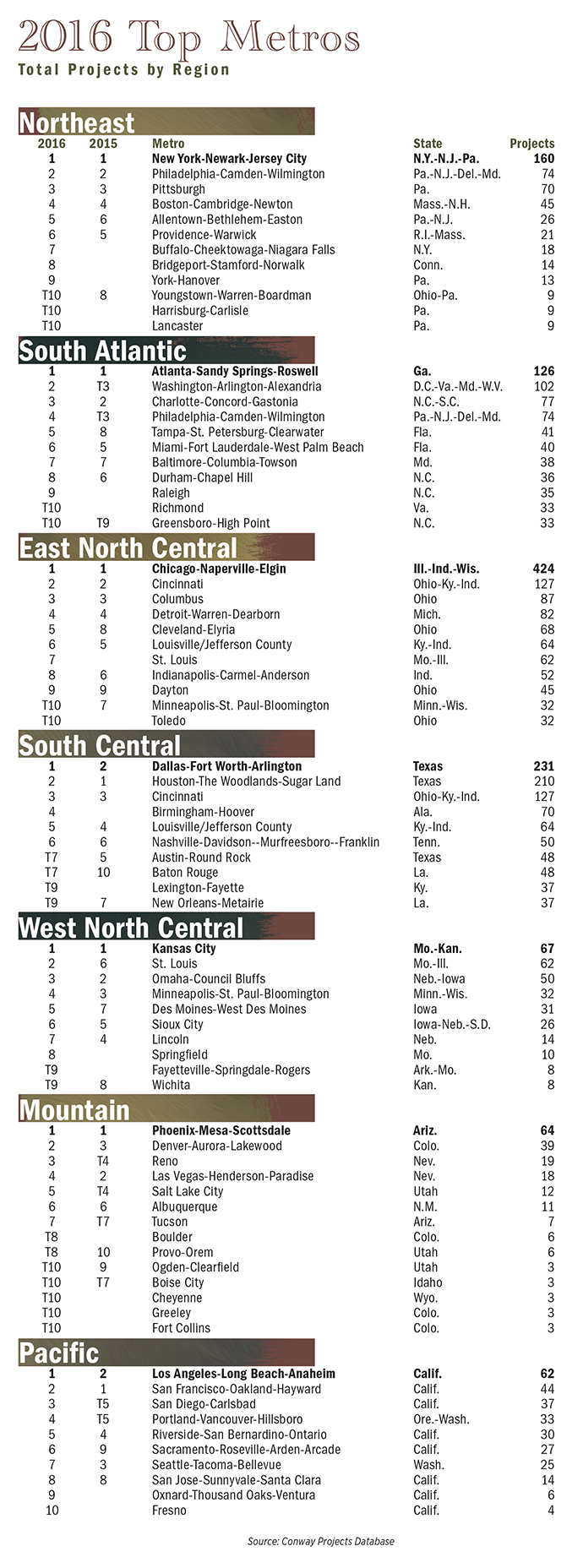

Among the Tier-1 metros representing populations of 1 million or more, six of this year’s Top 10 also rank among the most valued locations across multiple sectors in the forthcoming World’s Most Competitive Cities report, to be released later this spring by Site Selection publisher Conway Inc., EY and Oxford Economics. Evaluated for their attractiveness across 12 different industry sectors, Dallas-Fort Worth appeared in the top five nine times; Chicago, Cincinnati and Houston showed up seven times apiece; Atlanta made the cut in four sectors; and Detroit tallied three citations. All six were among the top 50 globally in terms of top-five appearances.

That’s just one way to slice business intelligence from the location data resident in Site Selection’s Conway Projects Database. There are other perspectives too.

Over 2,100 corporate facility project investments landed in this year’s total of 30 Top 10 metro areas across three population tiers. So we wondered: How many companies have developed a habit of investing in top-ranked cities?

Sorting the 2016 data by company name reveals that Accenture, for instance, has chosen to invest in locations in three Tier-1 Top 10 metros: No. 1 Chicago; No. 7 Washington, DC; and No. 8 Columbus, Ohio. Amazon … well, they seem to be investing everywhere, don’t they? But everywhere in this case means multiple investments apiece in Chicago, No. 2 Dallas-Ft. Worth, No. 4 New York and No. 5 Cincinnati.

Automotive giants Fiat Chrysler (FCA) and GM go full-out cross-tier. FCA is growing facilities and headcount in Tier-1 Greater Detroit (Warren); Tier-2 Toledo; and Tier-3 Winchester, Virginia-West Virginia. GM’s 2016 projects include growth in Detroit and Toledo too, as well as Tier-2 leader Bowling Green and Tier-3 Top Metro Bay City, Michigan.

Fedex leads all 2016 investors with projects in six of the 30 Top Metros, including the two Tier-2 metro areas of Dayton, Ohio, and Durham-Chapel Hill, North Carolina … and yes, Chicago.

The Windy City keeps coming up. There are reasons for that, says Matthew T. McGuire, who served under President Obama as the US executive director at The World Bank Group. A financial services executive from Chicago, he previously served as director of the Office of the Business Liaison at the U.S. Department of Commerce, which under Chicago native Obama was headed by a third Chicagoan, Penny Pritzker.

World Business Chicago worked with more than 180 companies in 2016, in coordination with the City, bringing nearly 9,000 jobs to Chicago. McGuire says Chicago is a great example of a competitive global city, due to such factors as its central location, a strong cadre of universities, hard-wired digital economy infrastructure from the days of the first Mayor Daley, and forward-looking transport infrastructure harkening to the city’s role as “hog butcher for the world,” in poet Carl Sandburg’s memorable phrase.

“It’s probably my favorite city,” McGuire says. As for its secret, “There is something to the agglomeration of young, talented, entrepreneurial people” in a place where they “want to be around other people doing exciting things.”

No wonder investment research firm PitchBook found early this year that the city led even the Bay Area and New York when measured by percentage of profitable startups.

Diversified and Dependable

In remarks at last year’s TrustBelt conference in his city, Mayor Rahm Emanuel offered ballast for those remarks, noting not only the metro area’s 16 four-year schools (more than any city but Boston) but its steady flow of talent from Big 10 universities throughout the Upper Midwest. “Every year and summer, like clockwork, around 140,000 freshly minted four-year degrees land in Chicago to start their career,” he said. Moreover, the city’s community colleges, which have about 115,000 enrolled, have been revamped to add more industry-sector specialization — for example, healthcare at Malcolm X, transportation and logistics at Harvey — to keep companies of all sizes supplied with the workforce they need.

Analysis released in February by Peter Bernstein, vice president at RCF Economic & Financial Consulting, Inc., shows that the Chicago area and the rest of Illinois both suffered substantial job losses during the Great Recession, but only the Chicago area has recovered its lost jobs, and in fact the area reached an all-time high in employment in 2016. Greater Chicago accounts for 85 percent of all private sector jobs added in the state of Illinois since the Great Recession.

Emanuel also noted the metro area’s leading position when it comes to economic diversification. “No one sector of our economy drives more than 13 percent of our employment,” he said. That’s why analyses from sources such as IBM, The Economist and A.T. Kearney keep ranking the city at the very top in terms of competitiveness and FDI attractiveness. He pointed to the four Ts: talent, transportation, technology and transparency. That final element has been crucial as the city has dug itself out of a structural deficit over the past five years, resolving pension fund revenue streams while still growing the economy. “Businesses small, medium and large want to see certainty, but also see the public sector use its political will to address its challenges,” Emanuel said. “We have not ever shrunk from it. Denial is not a long-term strategy. Our strategy is to double down on the key elements of our economic strengths while addressing the challenges.”

Parochialism isn’t a long-term play either. The stakes are too big.

“For 30 or 40 years, it was Chicago versus the suburbs.” he said. “It’s not true — it’s metro Chicago versus metro Los Angeles, metro Tokyo and metro Berlin.”

To DFW … and Beyond

How do cities known in part for their traffic congestion keep attracting more and more company facilities and jobs? Maybe in part because of the traffic.

Top Metros such as Atlanta, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth, while driven by economic development groups associated with their signature cities, don’t let center-city boundaries define them any more than a baseball diamond would define an entire ballpark. What companies, developers and governments are discovering together is the value of the town center — denser, more urbanized areas that aren’t necessarily in the core urban center, and have their own critical masses of major employers, amenities, residential growth and infrastructure. Close enough to benefit from their big-city progenitors, in other words, but big enough on their own to take a chunk out of the population’s average commute time, even as their regional planners move forward with transit improvements.

Plano, Texas is a prime example of a community helping its greater metroplex achieve continued greatness. It’s a place Dallas-based KDC has been investing in for a quarter-century, from projects for Intuit and The Campus at Legacy to recent office campuses for JPMorgan Chase, Liberty Mutual, and Toyota’s North American headquarters and a FedEx Office facility at Legacy West. The developer in January announced an agreement with Gabriel Legacy to promote and develop acreage on two tracts in Legacy Business Park — some of the last remaining undeveloped land in the area — for corporate development. Over the last 27 years, KDC has produced approximately 30 million sq. ft. (2.8 million sq. m.) valued at over $5 billion.

Mohammed Elahi, deputy director of economic development for Cook County, says improved transit such as TIF-assisted investments of $2.1 billion coming to modernize the Chicago Transit Authority’s red and purple lines as well as plans comprising the Connecting Cook County strategy are simply capitalizing on the American crossroads infrastructure that landed in the region a century ago.

Having worked for the second Mayor Daley in the 1990s, he’s always known the city proper, but has since seen with new eyes great industrial as well as live-work-play potential in south suburban Cook County. It’s not that far, really, from O’Hare,” he says, and is seeing new highway and intermodal rail investment, as well as early work toward a new cargo-oriented airport building out from general aviation facility Bult Field.

But the flight to comfort interests Elahi.

“I want to focus on the town center,” he says, noting the 45 municipalities he works with. “All these people who drive 10 or 15 miles, where is the biggest investment of their lives? Their homes. Why not create something for them so they can walk to the main street?

“It’s an emotional satisfaction that’s intangible,” he says. “When you are happy as a person, you’ll do amazing things. If I have my way, I’ll help create a University Avenue like in Palo Alto in every south suburban town.”

Just Right

Medium-sized cities benefit from a potent blend of the small-town vibe Elahi dreams about, and the capacity for big-time industrial, tech and services projects.

The top investments in Tier 2 metros came from the energy, software and automotive sectors, with Fiat Chrysler’s $700-million expansion in Toledo leading the way. Toledo also claimed the second-largest single investment among Tier 2s, courtesy of GM, which announced a $650 million expansion of its Toledo Transmission Plant, which employs some 2,000 workers. Microsoft and Facebook each invested heavily in data operations in Des Moines, with Microsoft pouring more than $1.3 billion into Des Moines-based data centers and Facebook beefing up a server farm to the tune of $550 million.

Cities in eight different states are represented among the top 10 metro areas with populations ranging from 200,000 to 1 million residents, otherwise known as Tier 2 metros. Ohio, with Dayton coming in at No. 3 and Toledo ranked No. 7, placed two entries in the top 10, as did North Carolina, with Durham-Chapel Hill placing No. 5 and Greensboro-High Point ranked sixth. Add the Hickory-Lenoir-Morganton MSA, which finished 14th in Tier 2 for new projects and expansions, and North Carolina achieves the distinction of placing three metropolitan areas in the top 20, an honor it shares with its neighbor, South Carolina (Greater Greenville, Greater Charleston and Greater Augusta, Georgia, which encompasses Palmetto State territory across the Savannah River).

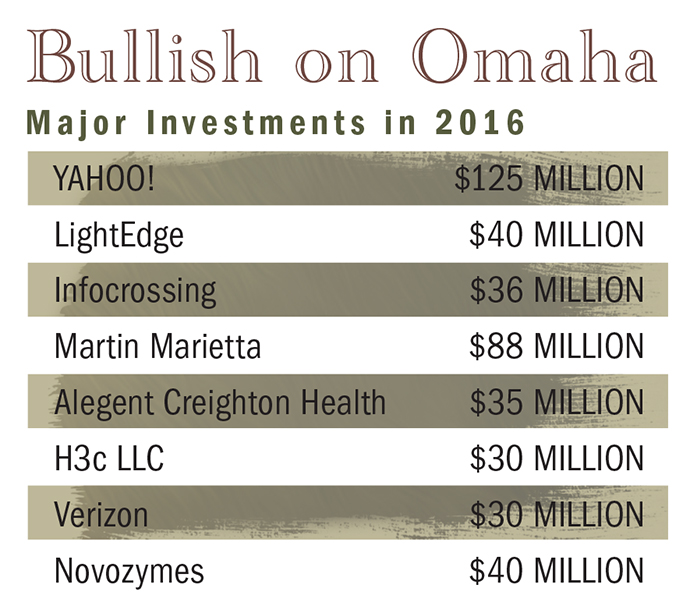

Omaha, Baton Rouge and Dayton finished 1-2-3 among metros in Tier 2, with the Omaha MSA recording 50 major projects and expansions and holding down the top spot for the second year in a row. In another big year for big projects, Omaha’s biggest of all was a $125 million expansion of a Yahoo! data center in La Vista. As part of the process, Yahoo! became one of the first beneficiaries of the state of Nebraska’s on-line permitting process, which can shave valuable weeks and months from the timetable for erecting new facilities. Nebraska’s online portal, one of only four in the nation, allows businesses to apply for stormwater and air quality permits with simple clicks of a keyboard.

“Making state government more customer-friendly has been one of my administration’s priorities to help grow our state,” says Gov. Pete Ricketts, adding that on-line permitting has enabled the state to “dramatically accelerate their delivery of permits.”

Other major investments in the Omaha region in 2016 came from an array of angles and industries, including IT and big data (D3 Technology, Light Edge, Infocrossing), minerals and commodities (Industrial Materials and Interstate Commodities), communications (Verizon), banking and insurance (Northstar Financial Services and Pacific Life Insurance) and renewables (Novozymes, Green Plains, Inc.)

For Baton Rouge, finishing second in 2016 meant climbing three notches from its fifth place finish in 2015. The Baton Rouge MSA did so with expansions in petrochemicals (Placid Refinery Company, Exxon Mobil, Shell Chemical, HR Nu Blu Energy), major industrials (Delta Machine & Ironworks, Cajun Industrial Design & Construction, Custom Metal Works, Inc.), plastics (Formosa Plastics, Westlake Vinyls), and technology (Spectrum Biotechnolgies, General Informatics).

With a third-place finish among Tier 2 cities, Dayton, Ohio registered 145 major investments, the biggest of which came from automotive firm, Tenneco. The Illinois-based corporation is investing some $98 million to upgrade its Kettering Engine Facility that designs and distributes shock absorbers, struts, mufflers, manifolds and engine mounts. Tenneco occupies a 940,000-sq.-ft. (87,329-sq.-m.) building and employs 478 workers, a number that is to double when the expansion is complete.

In Durham and Chapel Hill, where Duke University and the University of North Carolina fight like jealous brothers in collegiate basketball, the rivalry goes on hold for economic expansion. The two storied college towns, 15 miles apart, belong to the Durham-Chapel Hill MSA, which, for the second year in a row finished in Tier 2’s top five performing markets. The Durham-Chapel Hill metro scored in double figures in 2016, accumulating 35 major expansions including projects by giants such as FEDEX, Fidelity Investments, IBM, Glaxosmithkline and BlueCross BlueShield.

Knowledge Conversion

Girded by the presence of its two nationally recognized universities, the Durham-Chapel Hill MSA is also building out an impressive infrastructure for entrepreneurship. Duke runs an off-campus “Innovation and Entrepreneurship” program that aims to expand learning “to include the conversion of knowledge into real things and real actions to make a real difference in people’s lives.” The Duke initiative is housed in “the Bullpen,” the former downtown home of Imperial Tobacco Company, which the university converted into an entrepreneurial hub complete with space for classrooms, events and collaboration.

A short walk from the Bullpen is American Underground@Main, part of a local incubation program supported by Google. AU says startup companies it hosts have raised upwards of $26 million. Biometrix, which makes wearable sensors that can detect physical injuries, was founded in a Duke dormitory before moving into AU.

Biometrix founder Ivonna Dumanyan says the company raised some $1.3 million with help from American Underground.

“The funding,” says Dumanyan, “has allowed us to actually launch the product. We’ve been able to take that capital and immediately invest it in production. I came in here with my team as a student. It’s really allowed us to grow and learn from other individuals and administrators. Everything from fundraising to making connections to recruiting.”

Tatiana Birgisson avails herself of American Underground as CEO of MATI, which makes energy drinks that Birgisson, like Dumanyan, began developing in her Duke dorm room. MATI’s sales now reach in the six figures.

“This year,” says Birgisson, “we created 15 jobs. Half of them are in sales and marketing and the other half are in manufacturing. Being part of the AU is really important to us and not just because it helps us to retain talent, but it’s a great place to work and has a strong community.

More Ice Cream & Corvettes? Yes, please.

Expansion-minded Kentucky, which finished seventh in the nation for overall projects and second per capita, placed three cities among the top ranks of Tier 3 metros, which are those metro regions with populations of less than 200,000 people. The Kentucky cities of Bowling Green (ranked no. 2), Owensboro (tied 7th) and Elizabethtown-Fort Knox (tied 9th) all finished among Tier 3’s top ten metros.

Two states, Virginia (Winchester, tied 4th and Harrisonburg, tied 9th) and Michigan (Bay City, tied 9th and Saginaw, tied 9th), placed two cities in Tier 3’s top ten, while Iowa (Sioux City, no.1), Georgia (Gainesville, no.3), Louisiana (Alexandria, tied 4th), Wisconsin (Janesville-Beloit, tied 4th), Minnesota (St. Cloud, tied 7th), and North Carolina (Burlington, tied 9th) each contributed one metro each to the list.

Sioux City, which repeats as Tier 3’s leading metro, tallied 26 major expansions in 2016, the biggest by Wells Enterprises, the parent company of Blue Bunny Ice Cream. Wells followed up a $19.3-million investment in 2015 with plans for $40 million expansion announced at the close of 2016. Wells has been in business outside Sioux City for more a century.

“Wells remains in Le Mars and the Siouxland area due to an excellent work force, quality of life and business climate,” says Lesley Bartholomew, director of corporate and employee communications for Wells. Much of the company’s 2016 investment is to go toward a 6,000-sq.-ft. (557-sq.-m.) addition to its South Ice Cream plant. The company is adding two production lines and plans to create 81 new jobs paying at least $19.31 per hour.

“We continue to see increased sales in both novelties and packaged ice cream across the country,” says Bartholomew, “hence the potential need for these additional lines.”

Other 2016 investors in the Sioux City metro included soft drink distributor Chesterman, Sioux City Compressed Steel, Rocklin Manufacturing Co. and Nor-Am Cold Storage, which is sinking $18 million into new freezer space. The combined investments are expected to create about 20 new jobs in the Sioux City area.

Investments in Bowling Green helped to cement Kentucky’s claim as a Governor’s Cup powerhouse. After seizing the top spot for per capita project launches in 2014 and 2015, Kentucky’s second place finish in 2016 was fueled in large part by a $290-million investment at General Motors’ Bowling Green Assembly Plant, the biggest single 2016 investment among the Tier 3’s. The Bowling Green plant has made every Corvette produced since the early 1980s. It employs about 1,000 workers.

“The facility we took over here in 1981 was built in the ’60s by Chrysler,” says Kai Spande, GM’s Bowling Green Assembly Plant manager. “And they weren’t making car parts, they were making air conditioners. In the late seventies, they decided to get out of the air conditioning business, and the building became available to GM.”

GM’s 2016 investment in the Bowling Green plant, though huge, is hardly the first in recent memory. A $71-million upgrade preceded the 2014 launch of Corvette’s seventh generation “C7” series, which produced a sales spike and the Automobile of the Year award from Automobile Magazine. But the C7 investment pales next to the sums GM is spending now, just a few years later, which are amounts not included in the company’s pledge in January to invest an additional $1 billion in its US operations for 2017. Over the past two years, announced investments at the Bowling Green plant have totaled $773 million. Among other ambitious projects, GM is nearing completion of a $439-million paint shop, whose primary workers, says Spande, will be robots. Robots supplied by Michigan-based FANUC have been integrated already into Bowling Green’s main assembly plant.

Spande refuses comment when asked whether a C8 Corvette is in the works. Momentum at the Bowling Green plant is palpable, though, given GM’s unprecedented investments there and the success of the company’s product.

“It’s without a doubt,” says Spande, “that the C7 is the most successful Corvette we have made in Bowling Green.”