San Jose is both the biggest dot on the map of Silicon Valley and the Valley’s neglected stepchild. While Adobe, Cisco, eBay and Paypal all have headquarters in the country’s 10th-largest city, the explosive, tech-infused mojo that has created astonishing wealth and brought high-paying jobs to neighboring Mountain View, Cupertino and Palo Alto has largely eluded San Jose.

“The reason tech companies haven’t gotten here is that tech didn’t start here,” says Case Swenson, a San Jose developer. Tech companies, says Swenson, “have stayed between Cupertino, where Steve Jobs started, and San Francisco, which is where the money is. They haven’t made it this far south.”

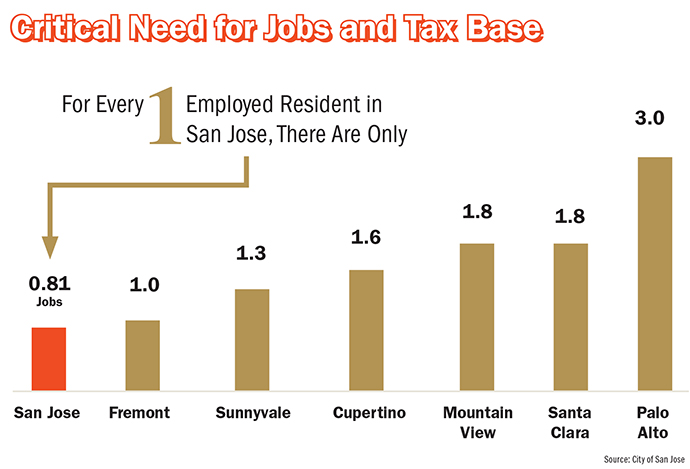

With a population of some 1.4 million people, San Jose is known as the Valley’s bedroom community, the provider of housing for tech workers who clog the outbound roads each morning on their ways to work elsewhere. Up to 70 percent of employed residents leave San Jose each day, says Bob Staedler of Silicon Valley Synergy, a land-use and government relations company. More than half of the people who work at Apple’s “Ring” commute to Cupertino from San Jose, which currently sits at a ratio of 0.81 jobs per employed resident. A recent city planning document states:

“San Jose is very fiscally constrained and will be so for the foreseeable future. An underlying reason is that San Jose has an imbalanced structure — it has a very large resident population/housing base relative to its small job/workplace base.”

Small wonder, then, that San Jose is agog over Google. After nearly two years of discussion, the search engine giant from Mountain View appears ready to pull the trigger on a massive, mixed-use corporate campus that could create up to 20,000 jobs, an eye-popping 65-percent increase in San Jose’s downtown workforce. The complex would be Google’s largest in the world. Google plans to house thousands of workers within the development.

‘The Place Where They Can Grow’

Under a Memorandum of Understanding approved unanimously in December by San Jose’s city council, Google recently paid $111 million in exchange for more than a dozen downtown parcels covering 11 acres (4.4 hectares) toward the tech giant’s plan to build a 50-acre (20-hectare) transit-oriented development of offices, shops and restaurants. Google envisions a campus of up to 8 million sq. ft. (743,224 sq. m.). In all, the company has purchased some 51 parcels of largely underused property and now controls a swath roughly a half-mile long.

The city hopes that, in addition to creating tens of thousands of new jobs, the Google development will generate the downtown buzz that San Jose craves, as well as millions of dollars in needed tax revenues for underfunded city services.

“Google,” says Swenson, CEO of his eponymous development company, “is absolutely some of the best news we’ve had since Adobe coming to town in the ‘90’s. It’s creating a huge amount of excitement.”

City officials, developers and real estate analysts cite several factors that have coalesced to make San Jose increasingly attractive to tech firms traditionally ensconced in Silicon Valley’s smaller enclaves.

“There’s a need for space in the Valley that’s getting tighter and tighter,” says Nick Goddard, senior vice president of Colliers International. “The freeways pointing north out of San Jose are packed in the morning, and pointing south they’re packed in the evening. Employers,” he says, “are losing hundreds of millions of dollars of productivity per year, and they realize that traffic is only going to get worse.”

“Google is absolutely some of the best news we’ve had…”

Developer Joshua Burroughs believes that San Jose’s relative abundance of available property has begun to tip the balance in its favor.

“All those peninsula cities have had an outrageous amount of growth the last decade, and they don’t have the infrastructure to add any more capacity,” says Burroughs, COO and senior vice president of development at Urban Catalyst, a newly launched investment fund supporting local Opportunity Zones. “San Jose is the place where they can grow.”

Employers, says Burroughs, “are getting pushed out of peninsula cities and they’re realizing that most of their employees live in San Jose and don’t want to commute anymore.”

To that extent, Burroughs cites the lifestyle preferences of the Valley’s millennial workforce as working in San Jose’s favor.

“Most of Silicon Valley,” he says, “is suburban. San Jose, particularly downtown, is an urban center. And when you look at the millennial workforce population, which is larger than baby boomers, that’s there they want to be. They want to be able to walk to work. They want walkable access to restaurants, events, cultural interactions and things like that. That’s what the San Jose opportunity is.”

The Right Moment Arrives

Burroughs agrees with local officials that the opportunity didn’t emerge from a vacuum, but rather is the result of years of strategic planning aimed at establishing downtown San Jose as a commercial and social center.

“There was a three-decade period when San Jose built up a bunch of infrastructure,” Burroughs says. “So, we now have the capacity to grow. We feel it’s ready for a turning point. We are reaping the benefits of the seeds that have been planted over the last 30 or 40 years.”

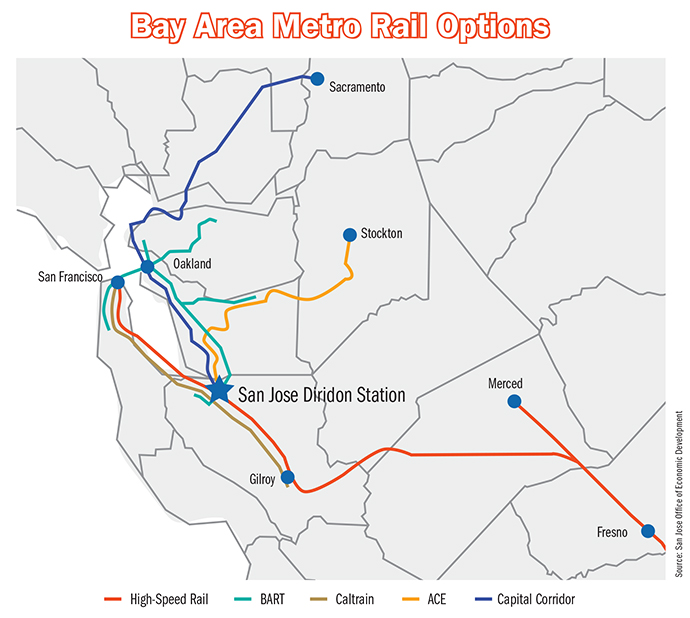

Underground fiber-optic cable went in, as did upgraded water and sewer infrastructure. The city established the basis of a regional transit hub with light rail, Amtrak, Caltrain and ACE Train (Altamont Corridor Express) all converging on downtown’s Diridon Station. SAP Center, which recently celebrated its 25th anniversary, became home to the NHL’s San Jose Sharks. Under a vision to create a downtown focal point, the city assembled tracts of land for a Major League Baseball stadium, a plan that fell through when the American League’s A’s couldn’t be pried away from Oakland. Still, the decision to purchase the downtown land proved prescient when Google came in and scooped it up.

“We knew that buying that property long-term was going to be good for the city, whether for a ballpark or something else,” says Staedler. “As the old joke goes, luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.”

The elemental lure for Google is San Jose’s effort to re-invent Diridon Station as a bustling, regional transit center. The $10-billion Diridon Station Area Plan, adopted in 2014, envisions the station connecting seven rail lines, which, in addition to Amtrak and Caltrain and ACE, would include high-speed rail, VTA (Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority), and BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit). The arrival of a BART line to San Jose, expected by 2026, is to complete a rail loop around San Francisco Bay.

Kim Walesh, deputy city manager and director of economic development, tells Site Selection that Benthem Crouwel, a renowed Dutch design firm, has been hired for the Diridon project. She says ridership through the terminal is projected to increase eight-fold by 2040 to 140,000 passengers a day, on par with the current volume of San Francisco International Airport.

“This will be on the order of what you’d see in Europe, a major intermodal station,” says Walesh. “Benthem Crouwel has done some of the most significant multi-modal stations in Europe, including Rotterdam Central Station, which is probably the best model for what we want to do here. We see it as a major destination in its own right, not just a pass-through station.”

A study commissioned by the city, released in November, predicted that the Google transit-oriented village would add 8.5 million sq. ft. (789,676 sq. m.) of prime downtown office space, an increase of roughly 85 percent.

“We’re making some pretty big decisions right now that have implications for private development and the public space,” says Walesh. “We want to maximize the station, the transit, the urban fabric and the private development that happens around it.”

By July, says Walesh, planners expect to determine the orientation of the station, alignment of the rail system, parking for cars and bicycles, bus access, and how the new station might mesh with the areas around it.

Google’s entry into the equation adds flesh to the bone of the city’s ambitious vision, and local authorities expect the company to be involved in the design of the station and its surrounding footprint.

“We had always envisioned that there would be a master developer,” says Walesh. “We didn’t want to have piecemeal development, so we were delighted when Google saw the potential to expand downtown.”

The high-speed rail component of the Diridon plan was cast into confusion in February, when California’s new governor Gavin Newsom appeared to scale back the $77-billion state-wide project, including a San Francisco-to-Los Angeles connection that would pass through San Jose.

“Let’s be real,” the governor told a joint session of the California legislature. “The current project, as planned, would cost too much and, respectfully, take too long.” Newsom declared that “there simply isn’t a path” to get from San Francisco to L.A.

Clouding the situation, Newsom added that he’ll continue to back “bookend” projects intended to bolster commuter rail lines in the Bay Area, which could eventually carry high-speed trains.

Elisabeth Handler, public information officer for San Jose’s Office of Economic Development, tells Site Selection that the planned multi-modal transit station “will become a reality” either way.

“We are proceeding with our work on high-speed rail, discussing San Jose’s proposed options with California High Speed Rail and supporting their outreach in our community. The Diridon Integrated Station Concept Plan,” Handler writes in an email, “is continuing with its work to plan a transit hub that provides a seamless experience for riders, while integrating into the fabric of the distinct neighborhoods that surround it.”

The Anti-Amazon

Google will benefit hugely from San Jose’s 11-figure investment in Diridon Station. But Mayor Sam Liccardo wants everyone to know that negotiations with Google bear nothing in common with Amazon’s search for new headquarters cities, through which the company openly solicited incentives including “land, site preparation, tax credits/exemptions, relocation grants, workforce grants, utility incentives/grants, permitting and fee reductions.”

Liccardo, in a Medium post dated November 28, declared that:

“Google will pay full freight for land, taxes, fees and additional community benefits … in stark contrast to other cities handing out billions in local tax dollars to attract big companies. We offered Google no subsidies, and they didn’t ask for them.”

Further:

“Whether it’s the tens-of-thousands of new jobs available to our residents, the roughly $10 million in net annual City revenues available to enhance public services, or the community benefits that Google has committed to provide … San Jose residents have much to gain if this project ultimately comes to fruition.”

Liccardo says that for the land it has purchased, Google paid $237.50 per sq. ft., two-and-a-half times what neighboring properties appraised for in 2017. Even so, it’s well below what Google paid as part of its recent $1-billion office park purchase in Mountain View. The Diridon transit center is likely to increase the value of the land surrounding it exponentially, including the property Google purchased.

Google, says Walesh, has begun to develop a master plan for its 50 acres, which the city must approve. At the same time, the city is to revise its original Diridon Station Area Plan, whose anchor was the ballpark that never came to fruition. In contrast to Amazon, officials say, Google will pay its way in.

“Google is very interested in social equity…”

“Once we know what the project is,” Walesh says, “we will start negotiating with Google the development agreement, which will include the amount and a general spending plan for a community benefits contribution from Google to the city. We will have a process of understanding the increase in the value of the Google properties, and we’ll calculate and negotiate an amount that Google will pay to the city.”

The Google money, Walesh says, will go toward public improvement projects such as affordable housing, parks and public places, job training and education. Under a city council edict, 25 percent of new housing in the Diridon area is to be classified as affordable.

“Google is very interested,” Walesh says, “in social equity and what we can do together to make sure that local people and local place benefit from this development.

“What Google is really about,” she says, “is placemaking and working with the city to balance these different interests, whether it’s sustainability, social equity or fiscal feasibility. All of that comes together in a mixed-use development that is right at this massively expanding intermodal station and transit service. There’s a lot of interest in getting this right.”

Riding the Google Effect

Whether by coincidence or otherwise, the talk about Google landing in San Jose, which surfaced in June of 2017, has coincided with a surge of downtown development plans.

Within weeks of Google’s initial announcement, Adobe announced that it would expand its massive San Jose headquarters by adding a fourth office tower 18 stories high, which would allow the company to more than double its downtown workforce from 2,500 employees to around 5,500. Adobe was one of the first major tech companies to locate in the city, having erected downtown towers in 1996, 1998 and 2003.

“We are doubling down on San Jose,” said Jonathan Francom, Adobe’s vice president of employee and workplace solutions.

Citing a survey of city planning documents, the Mercury News reported in February that proposed downtown office space climbed from zero in 2016 to more than 1 million sq. ft. (92,903 sq. m.) in 2017 and 4.3 million sq. ft. (400,000 sq. m.) in 2018. The paper reported similar jumps in proposed hotel rooms, housing units and retail.

“There is a pipeline of projects in the hopper in downtown San Jose, and it’s a lot,” says Joshua Burroughs. “And it’s separate from Google. It’s millions of square feet of office proposed, tens of thousands of residential units, hundreds of thousands of square feet of retail.”

In January, Boston Properties, one of the country’s largest publicly traded developers, owners and managers of Class A office properties, announced a partnership with an affiliate of San Francisco-based TMG partners to co-develop a 1.1-million-sq.-ft. (102,193-sq.-m.) urban campus near Diridon Station. Boston Properties says the planned three-building campus, named Platform 16 and designed by Kohn Pederson Fox Associates, is to feature 15-foot floor-to-floor heights, more than a dozen large outdoor terraces and outdoor workspaces, as well as fitness and wellness facilities and a conference center.

“The area near Diridon Station has become one of the region’s most prominent locations,” said Boston Properties in a statement.

“There is a pipeline of projects in the hopper in downtown San Jose, and it’s a lot.”

Boston Properties says it expects to begin demolition and site preparation this spring, break ground in summer, and potentially complete the project as early as 2021.

“The planned development,” says Mayor Liccardo, “will help bring thousands of jobs into our city center with easy access to public transit and include a number of public space improvements that will help connect the Guadalupe River Park to Platform 16 and the rest of the Diridon Station area.”

Just east of the station, Swenson has broken ground on a 260-room residential high rise conceived as an off-campus housing project for students at San Jose State University. Named “The Graduate,” the project is to consist of a 19-story, L-shaped building with more than 1,000 beds and student-oriented amenities including an exercise center, swimming pool, sports courts and picnic areas, with retail space on the first floor.

Swenson points out that, as the project is under construction, much of San Jose’s frenzy of proposed development remains on the drawing boards.

“As far as people that are actually pulling permits and building, it hasn’t really been happening,” he says. “I love the energy in what’s going on around San Jose. As far as a boom, I don’t think we’re there yet. I think we’ve got a good shot at a boom when BART comes to town and when Google comes to town.

“If both of those things happen,” he says, “sometime around 2025 or 2026, then the boom will be official.”