We’ve all heard about the resurgence in US manufacturing by now, and we are familiar with examples of the reshoring phenomenon now several years old. It’s a feel-good story in the wake of a recession that made some good news seem even better. The problem is this feel-good story is fiction. Such is the conclusion of “The Myth of America’s Manufacturing Renaissance: The Real State of US Manufacturing,” a January 2015 white paper authored by Adams B. Nager, an economic research assistant at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation.

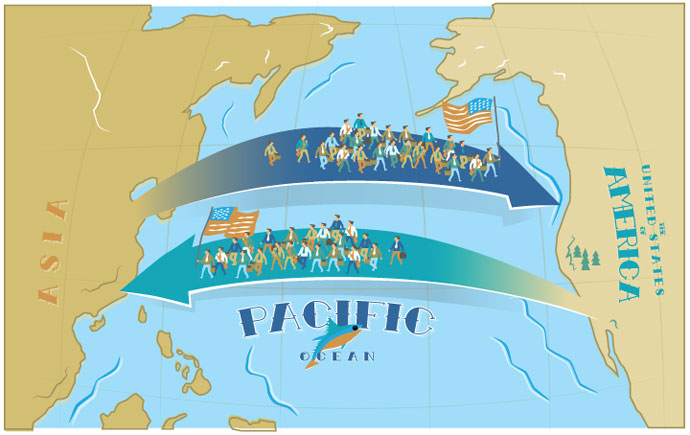

Onshoring is happening, Nager maintains, but take a closer look at the numbers. “Of the 120,000 jobs reshored in the last four years, there were equivalent numbers going offshore,” notes the report. “These figures are clearly an improvement from a decade ago, when in 2003 approximately 150,000 jobs left America, compared to about 2,000 jobs returning. However, this evidence makes celebrating a manufacturing renaissance feel premature.”

Five myths are behind the manufacturing renaissance narrative, Nager argues:

- China’s rising labor costs are reducing cost disparity. Not necessarily. “Reliability issues” undermine China’s statistical methodology in terms of wage growth. More to the point is labor cost adjusted for productivity, and China’s manufacturing labor productivity is skyrocketing relative to that of the US.

- Global shipping costs now give the US an advantage. Shipping costs did increase late in the last decade — up 635 percent from 2000 to 2008 by one measure. But the pre-recession overcapacity bubble has burst, and shipping costs are now back to pre-recession rates.

- The shale gas revolution will drive reshoring. Lower energy costs afforded by US shale oil and natural gas production was supposed to cause an uptick in manufacturing employment. In fact, this domestic energy production has had “a marginal impact on most industries … and will have no significant overarching impact on firm location choices.”

- A weak US dollar will lead to reshoring. The dollar did weaken throughout much of the 2000s despite government policies in support of a strong dollar. But not enough to make a difference. And it’s now increasing in value, notes Nagers, which is “less attributable to US competitiveness and more due to uncertainty abroad.”

- Strong US productivity growth is cutting relative cost differences. Robotics, “digital factories” and other cutting-edge productivity tools are in place and will pave the road to restoring US manufacturing strength. In time. Meanwhile, the report points out, “US productivity has averaged only 2.5 percent annual growth since 2009, compared to 4.2 percent growth in the European Union and 8.5 percent growth in China, as estimated by Boston Consulting Group.”

“The optimistic message of the manufacturing renaissance provides the public, business leaders and policymakers with a dangerous sense of complacency that reduces the urgency and necessity for Congress and the administration to take the bold steps needed to truly and sustainable revitalize American manufacturing,” Nager warns.

Can the US Still Compete?

Site Selection reached out to Nager in February for his thoughts on where to start — and whether the US really does make sense as a manufacturing location in 2015.

“Clearly, the US has advantages that companies deciding to bring back manufacturing or establish a new facility here can take advantage of, depending on the industry and the particular product line,” says Nager. “But this is very different than sweeping statements about the United States regaining ground in terms of global competitiveness. Even for manufacturers who could now produce at roughly comparable end prices in the United States, inertia as well as established supply chains, labor forces, and production methods keep them abroad. We hope that companies realize that superior potential for innovation, a more compact supply chain, and proximity to domestic markets will help increase their ability to compete now and moving forward. However, for many of the jobs that left, reshoring is not feasible.

“The United States should focus on policies to improve productivity, develop a skilled workforce, and build out its supportive innovation ecosystem,” he adds. “These reforms will lay the groundwork for the United States to see real job growth in advanced industries such as computers, biotechnology, and aerospace where the United States should be competitive, while positioning the United States to excel in next-generation industries.”