For people outside of the tax world it is difficult to understand that a rather boring topic such as international corporate taxation can have a game-changing impact on the attractiveness of certain jurisdictions over others. But the current BEPS initiative launched three years ago by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development can by all accounts be labeled as truly “disruptive” to the way multinational companies structure their value chains across countries and continents.

BEPS stands for “Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” and is the answer of the OECD — a club of leading industrialized countries — to shrinking tax incomes from multinational companies for its members.

The Buzzword: Substance

Taxes have always been a significant consideration for biopharmaceutical companies, which have as their main assets mainly intellectual property (IP) and brands — in other words, intangible assets which can be easily shifted from one location to another and thus are instrumental to reduce the global effective tax rate (ETRs) of the companies who own or exploit them.

In order to counter the excessive use of special tax regimes which often include special tax treatments for income from IP, the OECD has developed a BEPS action plan designed to reduce the arbitrage between different tax rates and different interpretations of tax principles that arise as a result of tax sovereignty of individual countries.

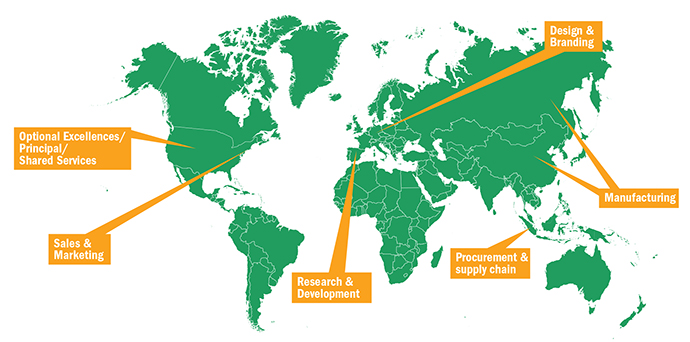

The OECD plan was outlined in detail in late 2015, and it is now up to the individual countries to adjust their national tax laws accordingly. In essence, BEPS requires that for multinational companies (MNCs) to be able to allocate profit to a certain locations, there must be sufficient qualifying substance located there. Mere holding of assets (i.e. IP) without enough substance in a certain (tax beneficial) jurisdiction does not qualify any longer for shifting profit to this jurisdiction. How is substance defined? The OECD sees substance as a combination of functions (FTEs), assets (i.e IP or manufacturing plants, etc.) and risks (i.e. contractual risks).

In addition, OECD also suggests to its member states to share information on taxation of MNCs through a so-called Country-by-Country Reporting (CbCR) system. MNCs above a threshold of €750 million (approximately US$845 million) in annual revenues will be required to report how much profit they generate in each country where they are active and how much tax they are paying per jurisdiction. This transparency will help national tax authorities challenge national tax filings of MNCs which operate in different countries.

Leaving the Island

Biopharmaceutical companies traditionally have been in the forefront of tax planning via the usage of low-tax jurisdictions for the exploitation of intellectual property.

With the BEPS being implemented in across Europe into the national tax codes, and the looming CbCR, biopharmaceutical companies are now reviewing their use of low-tax jurisdictions for the management and exploitation of intellectual property. Until now the management of intangible assets was focused on cost sharing and economic risk, whereas the BEPS Action Plan will require a closer alignment of actual “value generation” (profit) to “economic activity.”

In other words, the transfer of IP to low-tax jurisdictions such as Bermuda or the Cayman Islands with little or no substance is a model of the past. Basically all biopharmaceutical firms of significant size are therefore currently unwinding these structures.

Who Wins, Who Loses?

The fact that mere allocation of IP or other passive income generation assets to a low-tax jurisdiction is not a sustainable tax planning strategy any more not only has an impact on the value chain of the companies but also on the jurisdictions where such structures were mostly incorporated.

Offering a stable legal and political environment, operational grade infrastructure and little to no taxation will not be sufficient to keep these companies in a given country. The classic offshore locations already feel the decrease in demand for such structures with the respective impact on employment, GDP, etc.

There are basically three types of countries in the way they can be affected by BEPS in their attractiveness for foreign direct investment from life sciences companies:

- Countries with strong clusters of life sciences companies and an attractive tax and business environment: The UK and Switzerland — and to a certain degree the Netherlands and Belgium — are such examples: These countries can expect to be even more attractive in the future for biopharmaceuticals from overseas, particularly from the US and Canada. Due to the many companies from the bio, pharma and medtech fields, it will be possible for investors to locate regional HQs, manufacturing plants or research centers in these territories and staff them with locally available know-how. Thus they will comply with the mantra of “substance” necessary to benefit from the tax advantages which these countries can offer. In addition, the flexible labor laws in the UK and in Switzerland offer additional benefits for locating staff.

- The second type of countries have significant clusters of life sciences companies in their jurisdictions, but lack the benefits of an attractive business environment, i.e. less flexible labor regulations and non-competitive tax systems. Germany, France and, to a lesser degree, Italy, Spain and the Nordics belong to this group. Traditionally US/Canadian biopharmaceutical groups shied away from setting up larger centralized management functions in such countries, but in certain cases located manufacturing and R&D plants in them. For these countries there will be not too much of a change — they will keep their share of the business in terms of foreign life sciences direct investments. Their governments in certain cases may even benefit from high tax incomes due to reduced base erosion opportunities from the MNCs companies doing business there.

- The third type of countries are the ones on the losing end, which have built their business model predominantly on attractive tax regimes without having the support of a strong domestic biopharmaceutical industry that can back newcomers with qualified workforce, strong universities and highly specialized service providers. It’s not that these countries have not tried in the past — sometimes successfully — to attract more “substance” in the form of manufacturing or R&D operations, but the main reason for biopharmaceutical companies to come to these jurisdictions was taxes. Such countries — among them Ireland and Luxembourg — may need to rethink their investment promotion and industrial policy, and may want to refocus their efforts toward other core strengths such as competitive salaries, or a highly international and well-trained workforce and flexible labor regulations combined with very competitive tax systems and top infrastructure. They should also try, through incentives (i.e. for R&D and for startups) to make the best use of the huge potential of know-how and entrepreneurial spirit available.

How to Find Out?

Compliance with BEPS requires an in-depth understanding of where functions, assets and risk are located, and how they contribute to profit generation. A holistic and comprehensive value chain analysis sheds light on the existing structure and provides the base for realigning the business and the tax model in a way that makes the value chain sustainable and scalable. Such “future proofing” of the value chain is mandatory for biopharmaceutical companies in order to preserve value and to allow for future growth. From now on, value chain analysis should therefore be part of every sustainable tax planning and site selection process.

André Guedel is an expert in site selection for life sciences companies in Europe. He is the publisher of the KPMG “Site Selection Report for Life Sciences Companies.” This year’s report, in collaboration with EuropaBio and Venture Valuation, will be launched at BIO 2016 in San Francisco. André is the Head Sales and Business development at KPMG Tax Switzerland.

Dr. Hans Mies is a leading expert for value chain analysis and an advisor to many Fortune 500 companies. He is also a Director within the Tax Group of KPMG Switzerland.

Americas Snapshot:

A Tax Suspended, and Mexican Potential

The newly launched DataUSA product from Deloitte, Professor Cesar Hidalgo of MIT Media Lab and DataWheel includes public use microdata on employment that reveal the areas with highest comparative advantage. The data in April revealed that, on average, full-time employees in pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing have an average yearly salary of $100,379. The top locations with a relatively high concentration of employees are Somerset County (South), New Jersey; Hunterdon County, New Jersey; and Pottstown Borough, Pennsylvania.

The top locations with a relatively high concentration of employees in medical equipment and supplies manufacturing are Kosciusko and Marshall Counties, Indiana (the Warsaw area, home to Zimmer Biomet); and the Greater Minneapolis-St. Paul areas of Brooklyn Park, Maple Grove (East) and Osseo Cities, followed by Plymouth, Maple Grove (West) and Medicine Lake Cities.

According to a June 2015 white paper by Gerald Donahoe and Guy King, in 2013, spending on medical devices and in-vitro diagnostics totaled $171.8 billion, or 5.9 percent of total national health expenditures. The sector welcomed a reprieve in December 2015 when the US Congress passed a two-year suspension of the medical device excise tax in year-end legislation. “Congress and the administration have demonstrated that they recognize the negative effects of this tax. We urge policymakers to continue their work to eliminate the device tax and address other factors that are threatening the health care innovation ecosystem,” said AdvaMed Board Chairman Vincent A. Forlenza, chairman, CEO and president of BD.

An AdvaMed survey of its members found that two-thirds of respondents (representing 49 percent of total industry revenues) said that they had decided to slow or halt U.S. job creation as a result of the tax. The tax resulted in employment reductions of 14,000 industry workers in 2013 and years prior to implementation of the tax, with approximately an additional 4,500 jobs lost in 2014, and the cancelled hiring of nearly 20,500 employees over the following five years. However, most respondents pledged to reignite both hiring and R&D investment should the tax be fully repealed.

The 2016 Global Life Sciences outlook from Deloitte says life sciences firms in the US will be responding to healthcare spending, anticipated to grow by 4.6 percent annually through 2019, with Canada’s growing even faster (4.8 percent) due to an aging population. However, pharma growth may decelerate due to increasing payer pricing pressure on new, expensive specialty drugs. Deloitte says potential healthcare reform could open up opportunities in Mexico.

“In addition, Mexico’s medical tourism industry will continue to offer growth opportunities for medical device manufacturers and pharma companies,” says the report. “Mexico is already the world’s second-biggest medical tourism destination (behind Thailand), generating $3 billion in 2014. Mexican agencies expect that with increased investment, the country could grow medical tourism revenues to $10 billion to $12 billion in the next seven to eight years.”