Is all the talk about collaboration, synergy and happy accidents in open office plans more about projecting an image than imagining projects?

JLL recently released a white paper documenting “14 workplace trends reshaping corporate cultures in 2014 and beyond,” among them a return to privacy, compression of space per person and the end of command-and-control. Why the emphasis on membership vs. ownership and inclusive, cross-functional collaboration? One reason might be JLL’s own open-office experiment in Chicago four years ago. As Michael Berger, partner at Partners by Design, notes in elaborating his theory that open office just doesn’t jibe with Americans’ frontier mentality, two years ago JLL employees were asked to revert to more closed, private spaces.

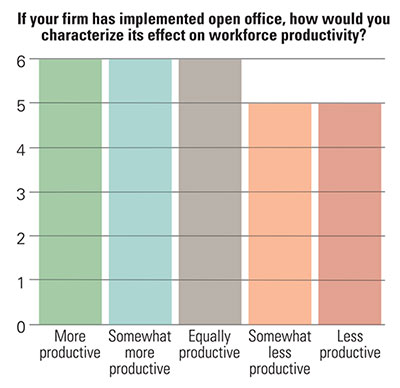

Site Selection conducted a survey in April to find out who’s pursuing open office, and whether, like some people’s experience of open marriage, it’s maybe not as fun as it sounds.

Judging from the 60 responses we received, some workforces were unhappy with the idea at first, but gradually have come to at least a neutral stance (or, as one respondent put it, “inevitable acceptance,” much like Dr. Kubler-Ross’s stages of death and dying). Others started wary and warmed to the concept. Still others experienced extreme dissatisfaction that never left.

An aerospace supplier pursued open office motivated by cost, not philosophy. Employees complained about not having any private time, and the sterile environment reminded them of a child-care facility. “Production fell way off,” said the respondent. “Too many distractions.” The concept highlighted what he calls “a big culture difference between the older and younger generation,” with the younger being more prone to that distraction. A respondent at a life sciences firm notes a similar lack of productivity due to distraction.

By accident, says the aerospace executive, the company learned that “the education the older generation received was superior to the younger generation. If we focused more on education and work ethic, just maybe an open office concept would work. Sure the technology has changed, but the person using the new technology needs to know how to apply it.”

The company ended up installing cubicles for up to four employees, which helped. As Nikil Saval relates in the new book “Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace,” the inventor of the cubicle, Robert Propst, intended his 1960s “Action Office” design to free a new generation of knowledge workers to perform with greater independence and autonomy. But hierarchies persisted, and management usually still got the windows.

Working Past the Noise

Open office is not without its champions, including some who are sensitive to the window issue. At a global electronics firm where open office predominates but management has doors, “the window line is generally left open for all to have a view through,” said one survey respondent.

One car company launched its model of open office in the 1970s in its European R&D division, and has since rolled it out on a global basis. Like others, the company has learned along the way to steer loud activity toward conference rooms, but the end results, says the respondent, is that the workforce is more productive, thanks to a “faster flow of information.”

“You have to develop new cultural norms.”

A survey respondent from big pharma noted, as with all corporate real estate and facilities innovations, the importance of buy-in from leadership. She also noted the need for flexibility: “Our concept is not only about open office, but about providing options for the colleagues to work from (quiet, concentration, collaboration, socialization).”

Another life sciences respondent notes, “One solution does not support the range of needs.” And a respondent at a global chemical company reports that the open design at a new suburban campus includes some semblance of a cube for everyone, with meeting rooms and quiet rooms spread around each floor.

Meanwhile, an open office concept implemented nine years ago in the manufacturing division of a big pharmaceutical firm has returned to closed offices for the VP and director, an evolution mirrored in other business functions.

At yet another life sciences firm, employees went from satisfied to extremely satisfied, using a system based on Knoll furniture originally implemented about three years ago on one floor at the company’s world headquarters. It’s now expanded to office sites globally on a country-by-country basis, with employees using a combination online/kiosk system to reserve workstations, private offices and conference rooms. The respondent also notes increased flexibility to work remotely, at management’s discretion. Another firm, using a Steelcase Mediascape product, has experienced frustration due to not being able to reserve space. And another echoes increased openness to telecommuting, as well as to flexible workday scheduling.

When asked about unintended consequences, one respondent noted the visual as well as auditory distraction: “Noise is not as challenging as conversation. Folks tend to lock onto a conversation. And since concentration takes focused energy to achieve, it is frustrating when knocked out of it.”

Among the most common observations by respondents was the realization of the need for more private meeting and work space for private phone calls, ranging from phone booth-type rooms to cubicle-style partitions. “People seem more clipped and apprehensive in their phone conversations, for fear that they are being overheard,” said one. But it can be a fine line. “We have ensured a number of smaller meeting rooms can also be used for private conversations or mini meetings,” said another. “Some employees would like to use them as offices though.”

No Slurping Please

Several respondents echoed this statement by one: “Good headphones are essential.” One respondent elaborated on this as part of a set of changes open office had brought about:

“You have to develop new cultural norms. Loud conversations need to gravitate to a meeting room, and use of headphones is a non-verbal cue that you need time to focus. People communicate in a faster, yet more authentic way. Instead of trying to read emotion into emails, people can use more natural communication, which alleviates many of the frustrations and misunderstandings that often occur through electronic communication.”

In other words, the good conversation outweighs the bad. Another respondent notes, however, the need to take longer conversations to a breakaway private space, as well as other reminders “to not play music too loud or at all; to not eat foods at the desk that have a strong odor; to avoid the office and work from home when sick; to not slurp loudly at the desk; to maintain a reasonable voice level when speaking on the phone or at the work station with others.”

One answer stood out above all others when it came to calibrating productivity:

“Employees who are productive,” said the respondent, “will do so in spite of their surroundings.”