A series of trends is building in the international system that will crash somewhat unceremoniously into the Trump administration. Some will complicate everything Trump tries to do. Others dovetail almost seamlessly with Trump’s rhetoric.

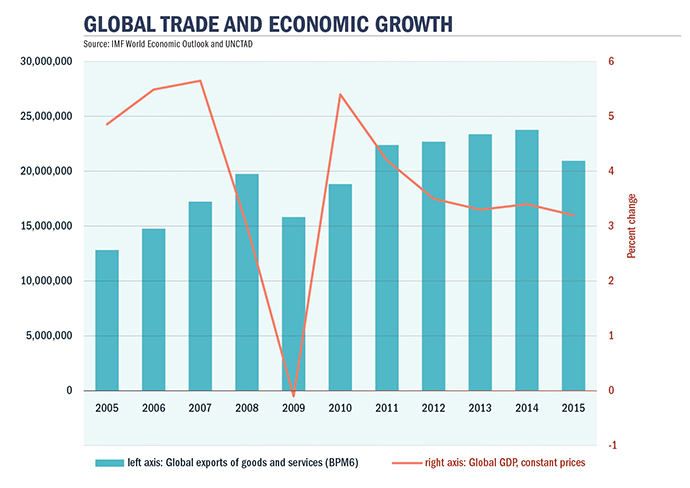

First, trade was winding down long before Americans went to the polls. Globalized, free trade didn’t happen by accident and wasn’t actually about trade. At the end of World War II, the United States created the trade order as a means of fusing entities as diverse as the United Kingdom, the defeated Axis, Algeria, Indonesia and even Communist China into an alliance against the Soviets. They received US market access and, courtesy of the US Navy, safety on the global oceans for all their trade in exchange for siding with the US during the Cold War. But the Cold War ended in 1989, and the whole strategy is outdated.

The complication is that the US is a largely self-contained, continental economy. Most of America’s free trade allies have trade dependencies triple or more that of the United States. The US enables trade but doesn’t need it. Everyone else needs trade but cannot enforce it.

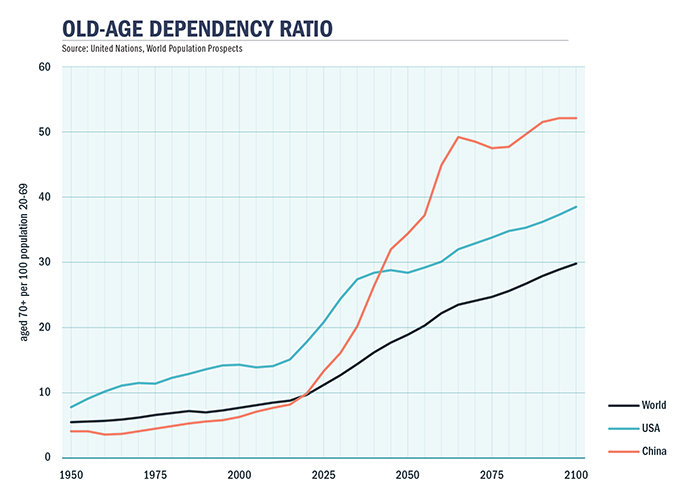

Second, aging is a global phenomenon. In nearly all the world’s leading countries, there are now more 40-somethings than 30-somethings than 20-somethings than teenagers than children. Most have already aged to the point that demographic recovery is impossible. Shrinking, aging populations do more than make pensions and healthcare an ever-larger share of personal and government budgets. They make countries more dependent on exports, because people over 45 consume less than people under 45. Just as the world becomes utterly trade-dependent, the world has become demographically incapable of supporting it.

The exception is the United States. The Baby Boomer phenomenon is global, but only the American Boomers had kids. Millennials are only omnipresent in the United States. Which means millennials only work and consume and pay tax in the United States. The US has a demographic future. Most other countries do not.

Third, the shale energy revolution is coming of age. Dozens of new technologies — pads and in-drilling and micro-seismic and water tanks and simultaneous operations — are ruthlessly driving down the price at which shale is profitable. In the major US plays, that number is now about $40 a barrel, and it will likely hit $25 sometime in 2019.

Be Very Wary

The Cold War is over, so the US no longer needs its trade-fueled international alliance. The US economy is largely self-contained, so it never needed international trade. And now energy — the last of the ties that bind — isn’t needed either. This is the world that President Trump is entering, which brings two topics to mind.

First, for those betting your economic future on China, be very wary. The modern Chinese economy was custom-built for the free trade system. It is export driven, and it is focused almost entirely on throughput rather than profitability. Loose financing drives not only China’s economic development, but also its social management system (give everyone a job so that they don’t protest the government). Corporate debt has tripled in a mere decade and is now at breakpoint levels.

Chinese demographics are nothing less than horrid. Courtesy of the one-child policy, the Chinese demography is in a not-all-that-slow-motion collapse. Having few children spikes consumption in the short term, because young workers can spend money on cars and vacations rather than diapers, but it doesn’t last. There is no replacement generation.

Every aspect of this system is in danger due to overextension at home. No wonder Chinese capital flight hit record levels in both 2015 and 2016 (2017 doesn’t look good either). Every aspect of this system is dependent upon unfettered access to the global economy and large, foreign markets, most notably the American market. Every aspect of this system is dependent on international energy supplies that the Americans no longer have an interest in safeguarding.

And this is before the transition to President Trump.

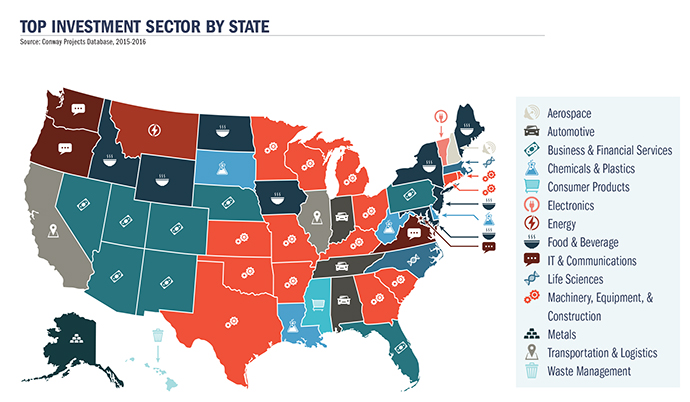

A geopolitical break between the United States and China is imminent, and the United States holds all the cards. The presence of Donald Trump will just make the coming split more … showy. Expect the biggest losses in those places where Chinese imports dominate the economy — Los Angeles and Seattle-Tacoma come to mind. Expect the biggest gains in zones where local skill sets, regulatory policy and infrastructure are well positioned to spin up replacement manufacturing capability. The entire I-35 corridor (Duluth, Minnesota, to Laredo, Texas) looks particularly good. A delayed boom will be felt in the areas most receptive to foreign investment — Alabama and South Carolina rank the highest — as foreign firms seek to relocate manufacturing capacity as close to US consumers as possible.

About that Wall

Second, a crisis with Mexico is also imminent, and this crisis is wholly a result of the coalition that elected Trump to office.

Populism comes and goes in American politics. Populists want change, they want it now, and they don’t care much about the implications down the road. They are also a prickly group; more than one leader has been eaten alive by his former populist supporters when changes didn’t manifest fast enough. By far the easiest means of satisfying the pro-Trump populists is to renegotiate a raft of topics with Mexico.

Here’s the challenge:

Mexico’s demography is strong and stable. Its internal market is growing quickly. It is energy self-sufficient. It is dependent upon North American trade, not global trade. Everything that is about to wrack the global economy largely passes Mexico by. This will make Mexico and its 125 million upwardly mobile consumers one of the fastest growing markets for decades to come. If there is one country the US should want access to, it’s Mexico. If there is one country with which a trade war would harm US economic growth, it’s Mexico. Yet Trump’s core supporters loathe Mexico, and Trump needs to establish his bona fides. Trump’s top challenge for 2017 is to square this circle.

There are several surprisingly constructive options.

Most illegal migrants into the United States since 2007 are not Mexican, but Central American. Mexico is even more concerned about this pass-through migration than the United States. A 2,000-mile-long wall cut through the open flats of the US-Mexico border would be pointless, but a 500-mile-long wall reinforcing the natural geographic barrier of jungle mountains which pervade the Mexico-Guatemala border could not only be effective but be done with enthusiastic Mexican participation.

Back in mid-2001, the United States and Mexico were about to commence negotiations on NAFTA II that included, among other things, border security. The September 11, 2001, attacks obviously sidetracked talks. Once again, the US has a president interested in redefining the relationship. The question is who will manage the talks?

Luckily, there is a powerful faction within the Trump coalition that has a vested interest in American-Mexican relations not going off the rails. The American state that does the most business with Mexico by far is the decidedly non-hippie bastion of Texas. The Texans are the logical interlocutors for whatever is next.

With a background in private intelligence, geopolitical strategist Peter Zeihan combines geography, demography and energy studies to reframe the future. His clients run the gamut from manufacturing and energy to agricultural and financial services to development boards and the U.S. military.