This commentary is the second installment of a three-part series.

As mentioned in part one of our three-part series on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), this treaty will be the most ambitious trade agreement ever negotiated. In this installment, we address four of the many legitimate questions raised about the treaty — transparency of the negotiating process, Investor-State Dispute Settlements (ISDS), food safety and geographical indications (GI).

Transparency: Not Quite Clear as Crystal

Secrets have a way of coming back to bite politicians. In response to mass demonstrations across Europe against what were viewed as “secret negotiations” of TTIP, the European Commission (EC) realized that the most effective way to counter charges of secrecy was to let the sunshine in. Last December, the EC took unprecedented steps to keep the public informed.

- As of December 1, 2014, European Commissioners are required to post all their contacts with lobbyists or interest representatives. They must also post any contact between lobbyists and their cabinet employees and directors-general.

- In January 2015, the EU released the legal texts for eight chapters of the TTIP agreement. Bernd Lange, European Parliament Trade Committee chair, called the publication an “important first step towards a public debate based on facts rather than assumptions and speculations.”

Calls for transparency haven’t been as deafening on the US side of the Atlantic where, according to data compiled by Chris Israel at ACG Analytics, a whopping 53 percent of Americans surveyed about TTIP had never heard of it.

Instead, the clamor for transparency issued from the usual suspects — watchdog activists and lobbyists for groups already opposed to the agreement — as well as from some strange bedfellows: ultra-conservative groups and Democrats wary of passing Trade Protection Agreement (TPA), so-called fast-track legislation.

In a placatory move, the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) did post an online fact sheet on its website in March 2014 during early TTIP negotiations. The fact sheet provided details of US goals and objectives, including how the agreement would benefit American workers, business and the consumer, and acknowledged the request for more transparency of the process, promising to share more information through the press, social media and the USTR website. The public was invited to comment via the website at comment@ustr.eop.gov.

A stakeholder engagement session was also hosted by the Office of the USTR in July 2014, in conjunction with the fifth round of TTIP negotiations held in Washington, D.C. Approximately 350 participants attended a series of “outreach events,” which included a briefing by the chief negotiators from the US and EU. US Ambassador Michael Froman and chief US and EU negotiators Dan Mullaley and Ignacio Garcia-Bercero heard from 50 stakeholders representing industry, small business, labor unions, academia, environmental and consumer advocacy groups. Mullaley and Garcia-Bercero offered remarks and answered questions from the participants.

Whether the moves on the part of the EC and the USTR are enough to satisfy critics remains to be seen. One thing is certain: Once the curtain is pulled back, it’s awfully hard to pull it closed again. When it comes to something as vital as passage of TTIP, the more light the better.

Investor-State Dispute Settlement: Protecting Investment, Enforcing TTIP

Imagine this scenario: A US company builds a plant in a European country under the provisions of a recent investment agreement. Everything is going smoothly until a new regulation on environmental protection leads to its expropriation, with what seems unfair compensation. How to settle the dispute? Local courts can’t help, since investment treaties are not the law of the land. This is when Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) becomes essential.

ISDS is the enforcer of TTIP: It protects investment by granting companies recourse to independent arbitration in the event of a conflict with a government. Investment will not thrive in countries where nothing prevents government from violating a foreign investor’s right. ISDS is a laudable idea, so what could go wrong?

Critics say ISDS will open the door for big businesses to hold governments hostage over profit losses, threatening the sovereign will of democratic states and leaving tax-payers with the bill. But the facts may not align with their critique:

- ISDS doesn’t always rule in the investor’s interest. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, of the 274 cases recorded by the end of 2013, about 43 percent were decided in favor of the state and 31 percent in favor of the investor. The other 26 percent were settled.

- The EU mandate states that the inclusion of ISDS won’t affect the government’s power to regulate.

- ISDS is not new. Over the last 50 years, nearly 3,200 trade and investment agreements among 180 countries have included investment provisions, and the vast majority of these agreements have included some form of ISDS.

- ISDS is especially good for small companies, as the specter of expropriated assets is much more threatening to them than to big firms. The Center for Strategic and International Studies reports that “the majority of US investors who have filed investment arbitration claims are firms with fewer than 500 employees.”

- The US wishes to set a precedent with TTIP to ensure that ISDS is included in future trade negotiations with China, a partner that does not have the same standards for investors’ protection as the EU does today.

The general debate over ISDS has become so divisive that it now threatens to undermine the entire TTIP negotiations. Of the 150,000 opinions received in the last survey by the EC, a crushing 88 percent were against an ISDS provision. It has become such a headache that the EU recently announced that the “decision on whether or not to include ISDS is to be taken during the final phase of the negotiations.”

Food Safety: A Race to the Bottom?

Chlorine-soaked chicken, pink corn on the cob and steroid-laced beef. To hear the European media and consumer watchdog organizations tell it, those ghastly-sounding food products would come to the table if TTIP were approved.

Concern about the lowering of food safety standards in the EU is one of the hottest of hot-button TTIP issues, and with $21.5 billion in combined agricultural and food trade in 2013, it’s an issue of enormous economic proportions.

Right or wrong, the perception exists that EU food safety standards are more stringent than those observed in the US. That perception is driven in part by differences in approach; the US takes a more cost-benefit stance to food risk assessment, focusing its attention on the end product, while the EU takes a much more cautious approach, regulating the entire process.

But regarding food safety and TTIP, both sides have made clear that the agreement will not substantively change existing food safety rules. The EU will maintain its high standards and restrictions on hormones and genetically modified organisms (GMO), and the US will keep its rules on microbial contaminants. Animal welfare laws already in place will be respected and, in keeping with all EU bilateral trade agreements, negotiators are setting up a formal dialogue on animal welfare with US regulators.

Both partners have stated that, while everything is on the table regarding the negotiations, they are looking to increase trade opportunities by hewing closely to principles in the World Trade Organization Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS), all of which must be grounded on “science and international standards or scientific risk assessments,” and applied “only to the extent necessary to protect human, animal or plant life, or health.” It’s difficult to read such statements and come to the conclusion that either the US or the EU want to lower standards, or face consumer outcry, just to make TTIP happen.

Geographic Indications: Your California ‘Champagne’ is Nothing but Sparkling White Wine

What do Washington State apples, Parma hams, Roquefort cheese, Cognac and Idaho potatoes have in common? They’re all delicious, pricier and, more importantly, named after their place of production. These products fall under the category of geographical indications (GI). In other words, their reputation and high level of quality are inseparable from their territory of origin.

(In some cases, the food safety and geographical indications issues have combined: In September 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration placed Roquefort and other cheeses on an import alert list because the agency’s limits for certain levels of bacteria — recently and significantly reduced by a factor of 10 — had been exceeded.)

Both the US and the EU are proud of their GI, but have different views on how to protect them. Europe, whose long culinary heritage has created a number of premium products highly valued by consumers, considers those place names intellectual property. The EU demands a high level of protection, allowing only local producers to use the geographic designations. S’il vous plaît, don’t call your red wine “Bordeaux,” unless you produce it within a 40-mile radius of Bordeaux itself.

This challenges the US system that tends to allow non-original producers to use those regions’ names. The US considers them generic and part of the general usage. As long as it is clear where the product actually originates, you can choose whatever name you want, as illustrated by Korbel California “Champagne.”

Important profits are at stake. If the EU were to obtain the protection of the region name “Champagne,” it would threaten American producers of sparkling white wine, accompanied by significant economic loss. On the other hand, Europe is not as competitive in the production of basic agricultural commodities and needs revenue from those GI products, which are sold at a rate 2.3 times higher than comparable non-GI products.

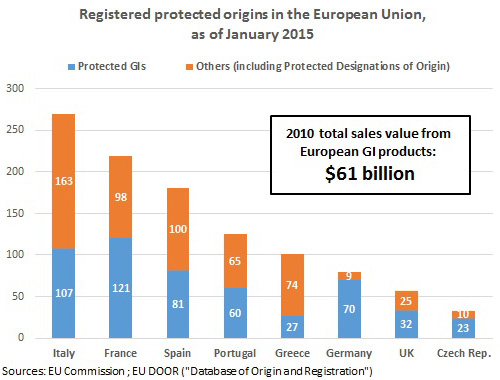

Nineteen percent of the value of the 2010 sales value of European GIs came from exports outside the EU (see graph), suggesting significant room for growth — but only if the EU can manage to protect its GIs.

While GIs are central in the EU trademarks classification, the US Patent and Trademark Office does not have a special registry for American GIs and, according to its website, “does not identify marks as GIs and does not examine marks on that basis.”

It is wise to seek clarification of legitimate concerns about provisions being discussed during TTIP negotiations. It’s also wise to seek answers from sources committed to providing information as free from bias as possible. But there comes a time when the public must decide whether they trust the leaders they elected to craft a treaty that will move their nations forward economically, or not.

If not, TTIP might be the least of their problems.