This market of 10 million will not be deterred. Two years after its revolution, which sparked the Arab Spring, Tunisia is emerging as an island of economic stability, and even one of relative political stability. The protests of early February this year were a reaction to the assassination of a political leader, Chokri Belaid, who was a leading reformer and opponent of measures that would stymie efforts to make this Mediterranean nation an increasingly welcome destination for foreign direct investment (FDI). Even that event will not change the fundamental business case for a Tunisian location, as thousands of foreign companies doing business there can attest.

Let’s address Tunisia’s perception issue right away, then. In reality, Tunisia is home to a highly educated work force that takes enormous pride in its business and industry. Business owners in the capital city of Tunis, in Sousse, Sfax, Bizerta and other locations will tell you that even as the revolution of early 2011 took place, workers were at their jobs, protecting property and equipment and ensuring that business continuity would never be in jeopardy. Outside, forces of change will always be present. But inside, there is work to be done, orders to fill, customers to supply.

Business sectors benefiting from this work ethic include mechanical and electrical industries — mainly component suppliers to automotive and aerospace concerns, textiles and clothing, agricultural and energy enterprises. The vast majority of products built, grown or assembled in Tunisia are exported, mainly to European Union-based companies, but also to other European countries, the Far East and other destinations. Tunisia’s proximity to Italy and France in particular, but to all of Europe, make it a nearby, low-cost location for not only transportation equipment sector suppliers, but also research and development functions. French is widely spoken in Tunisia, giving French companies the added bonus of language commonality, and English is widely spoken in the business community.

“FDI fell about 25 percent in 2011, due to investor sentiment following the revolution,” says Mohamed Mondher Laroui, general manager of statistics at the Central Bank of Tunisia. “But in 2012, it came back in some cases to levels above where it had been in 2010, prior to the revolution.” The manufacturing sector grew 61 percent, but there is general improvement in all sectors, he relates.

Is this growth sustainable, especially in light of recent events?

“Our growth and our sustainable development depend in large part on our openness to the world,” says Abdellatif Hmam, chief executive officer at Tunisia Export (CEPEX). “We must take advantage of the geographical position of Tunisia as a natural, regional hub on the north African coast, which is more important after the revolution. Now more than ever, we can not rely on our own capacities, but we must build technology partnerships and financial partnerships and business partnerships with our key contribution being our geographic position.” It is up to the government to recognize this and enact the appropriate policies to capitalize on this asset, he adds. Dubai has emerged as a key commercial hub in the Gulf region, because its rulers did just that, he points out. Singapore is another small country that has turned its size and strategic location to its clear advantage.

CEPEX is a key player in Tunisian companies’ growth plans in as much as their internal market potential is limited, but their international potential is not. Hmam says that in 2012 there was a 50-percent increase in companies seeking assistance in growing their markets outside Tunisia compared to the previous year. Agribusiness investors would be particularly welcome in Tunisia as demand for locally grown produce increases in the Persian Gulf region, Eastern Europe and elsewhere, he notes.

Clothing and textiles is another growth sector as demand in Europe for goods produced regionally increases. “Companies in this sector want us to accelerate free trade negotiations with the United States,” says Hmam, “because they are noticing that exports from Morocco, Jordan and Israel to the U.S. are growing. Morocco is offering free access to U.S. markets, and we must do the same.

A new, state-of-the-art airport, Enfidha-Hammamet International Airport, opened in 2009 about 80 km. south of Tunis.

“Our growth will be dependent on our openness to business,” says Hmam. “We know we must invest in our technology and logistics infrastructure to have a role in the value chain, to make this small country open for business worldwide.” If Tunisia’s highways, airports, seaports and economic zones are any indication, its infrastructure has seen plenty of investment.

Tunis-Carthage Airport is just 8 kilometers from the capital city, and a new, state-of-the-art airport, Enfidha-Hammamet International Airport, opened in 2009 about 80 km. south of Tunis, near Sousse and other tourist destinations.

Access to Europe Couldn’t Be Easier

Free zones can be found in Tunisia’s south, catering to energy-related concerns, and at Bizerta on the north coast, which is a key commercial gateway to European markets and the Mediterranean region. Tunisia is home to 10 existing technology parks, and 14 are under construction. The Bizerta Economic Activities Park (BEAP), a free trade zone on three sites (two are 30 hectares, and one is 21 hectares), opened in 1993 as a public-private partnership for promoting investment in Tunisia. Park administration serves as a one-stop shop for operators situated there, assisting in permitting procedures, building authorizations, work-force recruiting and liaising with local agencies, among other functions. Customs representatives are on site at the park, facilitating export activities, and the latest in security technology is in place throughout the park.

BEAP is just 60 kilometers from Tunis by highway and affords easy access to European seaports. Bizerta has an industrial heritage of 200 years and is known for its supply of labor. As of February, 82 projects were resident in the park, representing 57 industries, including pleasure boat manufacturers, electronic components for cars, textiles and garments, food processing, iron and steel metallurgy, packaging, call centers and software development. Aeronautics and pharmaceuticals are among the more recent sectors represented at BEAP. Companies that employ 100 to 150 workers per hectare occupied and invest on average €2.5 million are considered ideal candidates for a BEAP location.

More than 5,300 people work at the park, where approximately $500 million has been invested to date, 95 percent of which is foreign direct investment mainly from Italian, French, Swiss and U.S. companies. Casco is a U.S. automotive supplier that makes electronic power outlets and wire harness assemblies for BMW and other manufacturers at BEAP’s Menzel Bourguiba location, where it employs 400. Beji Baligh, financial controller, says the Bizerta site is a low-cost solution with plenty of available labor and fast delivery options to its European automotive customers.

Similarly, Italian die casting specialist Taurus ’80 opened a plant at Menzel Bourguiba in 2008 to produce zinc alloy components used in automotive manufacturing at a lower cost than at its plant in Grosso Canavese, Italy. Plant manager Alessandro Buiati says the company plans to expand at the site to take on more production volume, given the location’s clear cost advantages.

Engineers in Abundance

In Tunis, STMicroelectronics opened a design center for R&D at the El Ghazala Pole technology park, because it could find engineers in better supply than it could in France, and at a level of technical expertise that was comparable, says Hichem Ben Hamida, director. “There is no problem finding engineers here in Tunis,” he relates. An initial staff of eight has grown to 220 engineers in the past several years, now occupying three buildings at the technology park. The team conducts R&D on semiconductors, hardware and software, acting as an extension of ST’s southern France operation. Transit between Tunis and Marseilles is quick and easy, and the language commonality makes the Tunisian center a natural fit, he points out.

ST is immune from turnover issues at the moment, says Ben Hamida, as the rate of new companies coming to Tunis for R&D talent dropped off following the revolution in 2011 and a European business climate that is hampering companies’ expansion plans. “I have engineers here with 10 years’ experience, though the average is five to seven years,” he notes. “Each year we hire about 20 additional people.” Why Tunisia is not better recognized as an R&D center is not clear to Ben Hamida, because the higher education resources are plentiful. “The majority of engineering professors have years of corporate lab experience in Europe and the U.S. So language skills in the R&D community in Tunisia are superior, which benefits companies here greatly.” A bigger benefit, he adds, is the fact that the cost of the R&D talent in Tunisia is one-third the cost of the same talent in Europe

Ardia produces 3 million to 4 million electronic boards per year for European automotive companies at a factory in Tunis where it employs about 800. “The parent company, headquartered in Toulouse, France, had two needs — an increase in production and more R&D,” says Walid Rouis, general manager. “The strategy was to create a really dedicated R&D center in a near-shore country. At the time, I had seen studies of Morocco, Tunisia and Turkey, all of which are not far from Toulouse. It was decided to locate the new site here in Tunisia for proximity to the headquarters. I can fly there in the morning for meetings in the afternoon, which is very convenient. Also we have the infrastructure here and engineering schools that are comparable to those in France in terms of the degree programs.”

The company began operations in Tunis in 2005 with six engineers working initially on what Rouis terms repetitive and simple development tasks. Today, the site employs 184 engineers working all competencies needed for product development, including a mechanical department, a 30-person software development team and a group that works on embedded software for calculators in automotive components. The facility has become Ardia’s most important, says Rouis, given the high volume of product made and the R&D capabilities that point to more growth. In fact, a new China operation was shut down and the work consolidated at Tunis due to high turnover, cumbersome training requirements and the distance from Toulouse.

“We have highly skilled, well-trained engineers here in Tunisia,” says Rouis. “This is very important. We have the competencies. Second, we are well equipped in terms of IT infrastructure — comparable to what you will find in India or China or Europe. And we can count on our employees being here for a long time, unlike in China or India where turnover is very high. You can invest in your people, your human resources here and know that they will provide return on that investment.”

What should investors make of Tunisia’s political situation?

“The Tunisian people, and my engineers in particular, are quite mature,” says Rouis. “People here are very attached to stability and to having a good atmosphere. They are very much in favor of openness and steps that can be taken to encourage foreign direct investment. They want a healthy business environment. This is a country of services, and people know that their future is closely linked to the stability of the country.”

How To Beat U.S. Competitors

Eurocast, an aerospace components manufacturer, was established in Tunis in 2000 on the recommendation of a parent company in the U.S. that was under a cost-reduction directive from its main customer, General Electric, a leading commercial aircraft engine manufacturer. Another key customer is Woodward, based in Rockford, Ill. The company makes fuel injection systems made of cobalt and nickel alloys for the current generation of Boeing 737 commercial aircraft, among dozens of other parts, and is in line for work on the next generation engines now in development. Among the incentives of interest to the investor were Tunisia’s 10-year tax exemption and duty-free import and export provisions. “We located in the most industrial area of Tunis because it is close to the airport and we did not want to risk not having an adequate supply of labor, especially in aerospace,” says Adel Saoudi, director of operations. The population of qualified workers here is high.” The company employs 140 directly at the Tunis site and another 40 indirectly.

The location is paying off handsomely, says Saoudi. It began work on the GE business with an order for just 20 percent of its order for the fuel injectors. It now has 100 percent, having competed successfully against PCC, a supplier in the U.S. “In 2011, our business was $9 million. In 2012, it was $14.5 million. This year, we will be $18 million, so we will have doubled in two years, taking business from a U.S. company.”

GE would prefer to have the part built in Tunis and shipped to its engine plants in Massachusetts and Ohio, incurring higher transportation costs, than to have its competitor build the part in the U.S., Saoudi points out.

FDI Set To Ramp Up

Tunisia has weathered two years of economic challenges — the revolution of 2011 and European economic contraction throughout 2012, and the European Union is Tunisia’s chief trading partner.

The headquarters of FIPA, the Tunisia Foreign Investment Promotion Agency

“But foreign direct investment is doing extremely well,” says Hichem Elloumi, President of the Electrical and Automotive Industries Federation (UTICA). “But this is due largely to privatization, not industry as much since 2010.”

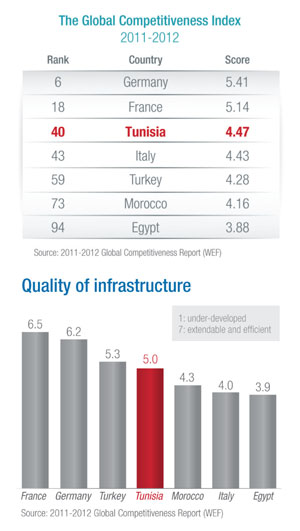

But Tunisia is very competitive, Elloumi argues, more so than Morocco and Eastern Europe. “We are always improving incentives for Tunisian and foreign companies, and the Ministry of Investment is right now preparing a new incentives program, which we are contributing input on.” Simplifying investment procedures is a central part of this plan and of an effort headed by the IFC to improve investment conditions.

And its strategic location remains a central asset, he points out, with easy access to the European Union and all of the Maghreb — north Africa and its 90 million population — as well as a host of Arabic countries in close proximity. “We are in an excellent location, logistically speaking.”

Elloumi says Tunisia will need to increase its visibility on the global investment stage, which it is doing, and will need to ensure social stability at places of employment and in general. To that end, UTICA helped compose a social contract between government, employers and unions. The goal is to make companies more competitive and their workers more content in terms of security and wage prospects. Workers and their employers will benefit. The government is addressing security, he notes, but U.S. companies that invest routinely in Mexico, Brazil and other markets would do well to weigh Tunisia’s strengths in that area, which are relatively enviable.

“In my experience, there has never been a security problem for investors here,” says Elloumi. Even before the constitution is finalized and a more permanent government is in place, all of which is scheduled to take place in 2013, investors will find a highly educated and motivated work force and low-cost investment climate.

“We are working to be more competitive with more growth and more employees using a system that will help companies be more productive. Tunisian and foreign companies we have shared this vision with have been very appreciative and supportive. We are in a transition period, but I am very optimistic about the future,” says Elloumi.

FIPA Tunisia’s director general, Noureddine Zekri, meets regularly with potential investors. His message, like STMicroelectonics’ Hichem Ben Hamida, is clear: “Tunisia delivers European know-how at a competitive cost.”

This Investment Profile was prepared under the auspices of the Tunisia Foreign Investment Promotion Agency. For more information, contact Mokhtar Chouari, international marketing director, at (216-71) 75 25 40, or visit www.investintunisia.tn.