Like the tiny Puerto Rican frog it’s named for, Coquí Radio Pharmaceuticals four years ago found its way to Florida, where the Puerto Rican company had reached an agreement with the University of Florida Foundation for a 25-acre parcel of land in Progress Corporate Park in Alachua County. But as with diagnosis and treatment of diseases, there are times when the first answer isn’t the right one.

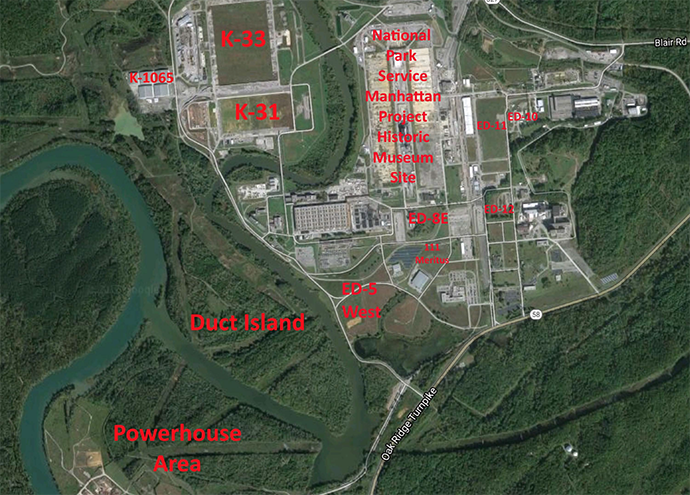

In April, one of the finalist states for that original decision (along with Louisiana) landed the project after all, as Coquí announced that the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) had officially transferred land for the facility and provided research support through the national laboratories in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The transfer of 206 acres at a site historically known as Duct Island in the Heritage Center Industrial Park places the company in a strategic location adjacent to federal research assets, Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and the Y-12 National Security Complex.

The Coquí facility is expected to be fully operational in 2025 and will provide 206 "high paying, permanent jobs," said Coquí in its announcement. Yes, that’s right: one job per acre.

It’s such a natural fit, it’s hard to believe it wasn’t the first pick the first time around. But it may also be a case of missing what’s right under your nose … and a case study for why regions who think their value and assets are widely known have to keep reinforcing that message.

In an interview with Site Selection as she prepared to travel to Oak Ridge, Carmen Bigles, founder and CEO of Coquí Radio Pharmaceuticals Corp., says the first site she was ever offered outside of Puerto Rico was in Tennessee, but admits she was not as familiar with the entire energy and nuclear fields then as she is now.

"When it was offered to me, I didn’t realize the gem of Oak Ridge, especially for a company like ours," she says. A few years later, she was asked to speak at a conference taking place at ORNL where she opened students’ eyes about the ramifications of their studies, explaining that it wasn’t just experiments, but work that could help save and improve human lives. During the visit, her eyes were opened too.

"We had spent a lot of money on the Florida site, but they made me an offer I could not refuse," she says.

Once fully operational, the facility will be the first of its kind in the U.S., which currently relies on imports to meet the demand for Molybdenum-99 (Mo-99), used in 18 million medical procedures a year in the U.S. Mo-99, relied on to diagnose and treat diseases including brain, heart, lung, liver, renal, oncologic, and muscle skeletal diseases, is the basis for the most widely used medical isotope in the world, Technetium-99m (Tc-99m), which is used in approximately 40,000 medical diagnostic procedures per day in the United States. With its short half-life, the isotope needs to be used in patients very quickly after it is created.

“Coquí is best positioned to meet the demand for lifesaving medical isotopes because our technology is commercially proven and is used in the current supply chain,” said Bigles in April. Design of Coquí’s facility is being led by Argentine firm INVAP — Coquí has an exclusive license with INVAP to use its technology in the United States. Among other medical isotope facilities INVAP has completed are the OPAL reactor in Australia, the ETRR-2 reactor outside Cairo, Egypt, and the NUR reactor in Algeria. Coquí’s facility will use an open pool reactor technology similar to that in the OPAL facility. And as with the original decision, the project is being led by construction and engineering firm Gresham Smith — based, as it happens, in Tennessee.

A Need for Medicine, and for Domestic Independence

As reported in this space four years ago, global supplies of Mo-99 were increasingly unreliable as facilities capable of producing the isotope age and shut down. That scenario hasn’t changed. Mo-99 shortages such as the one that occurred in November 2018 still occur. And the U.S. still has no domestic production source.

“This land acquisition provides many advantages," Bigles said in the April announcement. "Oak Ridge is home to several DOE and TVA nuclear facilities, providing a strong nuclear and engineering workforce." DOE has provided further support for the Coquí facility through research funds supporting Coquí’s partnership with ORNL and the nearby Y-12 National Security Complex to conduct further research on Mo-99 target plate fabrication and qualification.

“This research partnership is critical and supports our efforts to obtain Nuclear Regulatory Commission and Food and Drug Administration approvals for the facility," said Bigles in April. "The sooner we can begin producing U.S.-made Mo-99, the sooner we can minimize our dependency on foreign imports to meet critical U.S. medical needs.”

After all, Y-12 — part of the former Manhattan Project site that also includes X-10 and K-25 — exists in order to supply uranium. ORNL is a nuclear center of excellence with a strong pool of talent across the nuclear spectrum, and it’s an old hand at strategic collaborations. Moreover, says Bigles, the former K-25 — part of a 1,200-acre site now known as the Heritage Center — has its own fire department and emergency services, in a community that “understands nuclear,” she says. The K-25 site, operational for 40 years in uranium enrichment using the gaseous diffusion process, was renamed the East Tennessee Technology Park (ETTP) in 1989 and its mission changed to one of environmental restoration, waste disposition, and reindustrialization.

Coquí’s project isn’t the only one at ORNL building toward a new future from a storied past. In early May, U.S. Secretary of Energy Rick Perry and other officials broke ground on a new $95 million Translational Research Capability facility, or TRC, centrally located in the ORNL main campus area on a brownfield tract that was formerly occupied by one of the laboratory’s earliest Manhattan Project-era structures.

“This building will be the home for advances in Quantum Information Science, battery and energy storage, materials science, and many more,” said Secretary Perry. “It will also be a place for our scientists, researchers, engineers, and innovators to take on big challenges and deliver transformative solutions.”

A Clause Without Claws

Duct Island — so named because of the ducts carrying electricity from the powerhouse to the K-25 site — essentially forms a peninsula much like a tiny Florida, with surrounding lake providing a natural safety and security barrier. And plans are in place to build an airport just down the road, which Bigles envisions as perfect for helping to deliver medications to patients. Looking at the whole package, “I was like, ‘Really, you’re going to give this to us?’ You couldn’t refuse it once you understand the importance of being in this community of amazing, brilliant people.”

Helping the process along is the fact that the money Coquí spent on environmental documentation in Florida doesn’t have to be spent to the same degree in Tennessee, where the DOE itself had plenty of environmental data to work with.

But speaking of Florida … how did Coquí, which has offices in Florida until it registers in Tennessee, manage to hop away from its former deal?

“That was the end of 2015,” Bigles, who makes her home in Coral Gables, says of the change of heart. “We went back to the University of Florida, sat down with them, and they understood why the company had to go to Oak Ridge. The entire physics department understood it.” Essentially, while they regretted losing the project and its jobs, they understood that it wasn’t where Coquí belonged. And while the company was far along in its licensing with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, it wasn’t that far along with actual construction.

Bigles says the agreement with Florida included a clause allowing the return of the land if the project was not going to move forward, “and that’s what we did. At Oak Ridge, it’s different. It’s ours no matter what.

Notwithstanding the loss of the potential jobs in Florida, “The only people that lost money was our company, which lost what we had invested at the site,” she says. “But we don’t see it as a loss. We see it as a practice run.”

Bigles compliments the professionalism she’s encountered in both states and local regions. Now it’s time to get busy ramping up toward that 2025 goal of full operations, because the domestic need for more Mo-99 continues and the few international sites producing it continue to be unstable. “South Africa was shut down a couple months ago,” Bigles says. “Australia went offline as well … Every country manufactures for their people, and we get the scraps,” with Australia and the Netherlands being the primary sources lately.

“There is still a huge need for this. It’s not readily available,” she says of the new isotope facility. “I see the people suffering. I see it with our cancer patients at the clinics my husband, a radiation oncologist, runs: I also own two oncology clinics, so I see patients, I see them suffering, and see them needing different products. We need to advance medicine and make it more affordable, and we need medicines produced in-house and not outside.”

Ultimately, Bigles sees being part of the historic Oak Ridge site as an honor, and sees her company’s purpose as a new chapter in the area’s heritage of doing crucial things for the country. She repeats that she never realized the gem Oak Ridge represented. Now, she says, “I see Oak Ridge becoming a nuclear medicine center of excellence for our country.”