Nearly 90 years ago, Henry Ford and Thomas Edison were busy laying out a vision for a new kind of industrial Eden in northwest Alabama. It would be a “75-mile city” along the banks of the Tennessee River, filled with cheap power from the under-construction Wilson Dam nearby that had been started during World War I, along with nitrate plants for making explosives and fertilizer. They even took to calling it Detroit Park.

Instead, their big plans (and, some say, Ford’s presidential aspirations) were derailed by Sen. George Norris (R-Neb.), whose vision of America did not countenance the idea of placing such valuable assets in private hands.

The actions of Norris gave rise to a New Deal program known as the Tennessee Valley Authority, formed in 1933, when it acquired the 3,000 acres (1,214 hectares) from the U.S. War Department. At the time, only three percent of the area’s farms even had electricity. Today TVA serves large industry, distributes power via 158 distributors and reaches some 9 million customers across seven states.

TVA was formed to operate government-owned properties in Muscle Shoals; to develop water and power resources of the Tennessee River watershed; and to plan for the social and economic well-being of the valley. That well-being today may depend on the direction taken by the redevelopment of 1,380 acres (559 hectares) of TVA land, part of a TVA Reservation that now has sustained the region and the nation for decades.

In the summer and fall of 2009, TVA pursued an adaptive reuse study conducted by Lord Aeck Sargent Architecture, home to the Southeast’s largest historic preservation architectural studio. The 800-plus-page study looks at the property and its more than 70 buildings and makes recommendations as to the optimum way forward on the parcel, as TVA’s activities have gradually declined over the past 15 years.

The hope is to dispose of a unique parcel in the agency’s portfolio in a way that will benefit the region’s economy — with the private sector that so troubled Sen. Norris now at the heart of the land’s many possible futures.

“The primary driver is it provides an economic development opportunity for the region,” says Tony Hobson, project manager, TVA Reservation. At the same time, TVA would reduce its property costs by getting out of outdated buildings and land. “It’s a large piece of property, and underutilized, with some buildings in very good condition, that could be put back on the tax rolls.”

Hobson says the idea kicked off in 2007, but has picked up steam in the last 18 months.

“At this point, from the TVA perspective, we’re focused on doing the things to get the property ready for possible sale or reuse,” says Hobson. That includes an environmental impact statement by the first quarter of next year as well as a complete review of such facets as historic buildings, archaeological findings and transportation infrastructure. Hobson says the TVA team will use the Lord Aeck Sargent study “as a starting point for planning how this property can be redeveloped, and supporting stakeholders who want input into the planning process.”

If a single corporate end user came along right now wanting to buy the whole property with a vision to put the entire site to its own use, Hobson says that would be considered.

“Absolutely,” he says. “That’s exactly what we’re trying to do. We want to get the environmental review done. We have the local community involved. So if a developer comes in, there’s one voice the community speaks with. Developers have indicated if the review is done, and the communities support the effort, that puts you ahead of many sites.”

Warfighting to Fertilizer

The military connections to the property have continued from its strategic choice during the war to end all wars through today’s BRAC process that is bringing an end to many a military base.

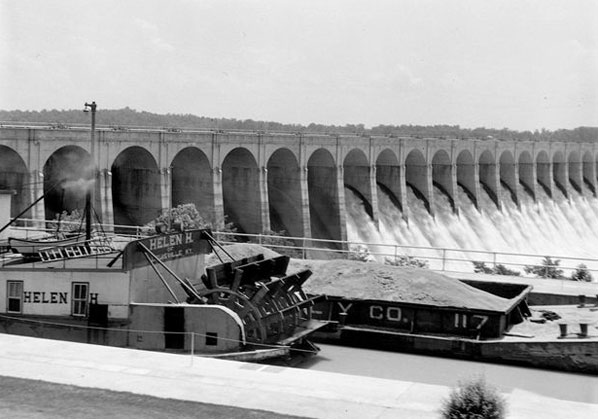

With the advent of World War I, Congress “authorized the construction of two nitrate plants powered by an adjacent hydroelectric facility, Wilson Dam,” explains the Encyclopedia of Alabama. At the time, most nitrates came from Chile, and U.S. government officials feared interruption of that supply chain by German forces. “Government engineers selected Muscle Shoals as the construction site because it had the most potential for the development of water power east of the Rocky Mountains. However, the war ended before the facilities could begin production.”

So President Warren Harding offered the dam and two nitrate facilities for sale or lease. Ford offered $5 million to lease the property, provided that, like many a power-plant-lakeside homeowner, he got something approaching a 100-year lease. Norris blocked it from proceeding, and Ford withdrew his offer in 1924. Perceived as a pariah at first, Norris over the ensuing years laid the groundwork for the creation of TVA in the name of flood control and economic development, work that paid off when FDR came into office.

During World War II, the TVA operations provided a huge percentage of the phosphorous needed for many munitions, and TVA’s system of river locks and dams accommodated inland construction of military watercraft of various kinds.

Central to today’s redevelopment process is the Northwest Alabama Cooperative District (NACD), officially incorporated in April 2009, and led by Muscle Shoals Mayor David Bradford. The idea for its formation came from a trip the TVA team took to Anniston, Ala., to the former Fort McClellan Army Base closed under BRAC, says Hobson. That property was transferred to a group formed as a district under Alabama law that allows the district to own property, but does not allow it to commit taxpayer funds from their towns. “They’ll help guide us in setting the plan,” says Hobson.

“Having been in this business for several decades, it’s both refreshing and unique to find multiple jurisdictions that not only talk about working together but actively seek to work together,” says Forrest Wright, CEcD, president of the Shoals Economic Development Authority, who first moved to the area nearly 20 years ago. “At the time I moved here, it was a vibrant, ongoing TVA property, with several thousand employees, and research going on, particularly around power production and environmental issues. They were just wrapping up the fertilizer aspect of that process.”

However, the International Fertilizer Development Center, an entity independent of TVA, still conducts important international research at a site on the property.

Wright has seen his share of redevelopment plans that have not gone anywhere, as TVA work has gradually gone away. “At this point it’s a large, underutilized piece of property, right in the middle of the quad cities area of northwest Alabama,” he says. “Both TVA and the communities want it to be used for what is proper and beneficial.”

Until now, development of the parcel in the quad-cities area of Muscle Shoals, Sheffield, Tuscumbia and Florence has taken place in bits and pieces of retail wanting to snip off corners of the property over the past 15 years or so. At one time the idea was broached to develop a golf course on the property to add to the popular Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail that cris-crosses the state. But none of the above has come to fruition. So it was time to get comprehensive, says Hobson.

Asked if that concept lends itself to selling to a single master planner, he says, “I think there would be some advantages to that. Sell it off to one developer, who manages it.” But the aim to offer various types of property on a mixed-use, research park or energy campus type of development might work against that notion, since most developers specialize in one type.

“We’ve indicated we would entertain either option,” says Hobson. “One tract, or if it needs to be sold in smaller tracts, we would consider that as well.”

In fact, the process is at an early enough stage that there are still plenty of parties to engage and possibilities to leave open. Says SEDA’s Forrest Wright of the parcel, “The slate is still clean on what it can become.”

“We’re planning to release the draft EIS this summer and looking at an August public meeting in response to the EIS,” says Hobson.

He sees a more complete engagement with the university community developing this fall.

Such engagement would reprise what TVA did during the Reservation’s prime years, as it worked with Auburn, University of Tennessee and other institutions on agricultural productivity issues that involved the use of the phosphate fertilizers made at TVA facilities.

Let’s Keep It Clean

TVA got out of the fertilizer production and research business, but it still has to face the remnants of that business, such as the 70-acre (28-hectare) phosphate slag heap adorning the northern portion of the redevelopment parcel.

Approximately 760 acres (308 hectares) of the Reservation property now have been converted to very popular recreational uses, featuring popular hiking and biking trails along the same stretch of river Henry Ford once saw as the promised land. But there are still promises to keep in terms of remediation. The primary environmental assessment focus will be on the slag heap, a radiological laboratory area and a building complex of 35 acres (14 hectares).

“There has been fairly significant cleanup of the property over the years,” says Hobson. “We want to be very forthcoming with what we know, and be diligent in our EIS, so we identify everything and make sure it’s done properly.

“There are four solid waste management units on about 64 acres [26 hectares] of the property, with no further action required except for continued monitoring,” says Hobson. “Our plan is that TVA would retain ownership of those. There are about 17 acres [6.9 hectares] cleaned up to industrial standards, which relates to the amount of time you can spend on that area and the exposure limits — working 16 hours a day would be fine, but you couldn’t build a house on it.”

TVA is now taking down the last two of 21 buildings that were deemed non-historic in nature. In older buildings, historic or not, there are issues such as lead paint and asbestos, says Hobson. “So as we go through this consultation with the commission, we’ll look at taking down the buildings that don’t contribute over time. We’re initiating a study to look at detail in the buildings and what would need to be done.”

The Lord Aeck Sargent study, done in consultation with retail and residential real estate analyst RCLCO, already has some ideas on what’s best to do with those buildings: “The greatest opportunity for redevelopment of the TVA Reservation will begin with the creation of an R&D campus.”

The study goes on to extol the attractiveness of making sustainability a key tenet of that campus. Such a campus could build on the area’s energy heritage while showcasing a new generation of environmental clean-tech leadership. “Green development of the site can help combat lingering negative perceptions of the Reservation due to known contamination,” it says.

It also could be a priceless opportunity for TVA to balance the environmental scales, even as it takes extraordinary remediation and cleanup steps following the massive December 2008 coal ash spill from a retention pond at TVA’s Kingston fossil plant in Roane County in East Tennessee, and a second, smaller coal ash leak at a plant in northeast Alabama near Stevenson in early 2009.

SEDA’s Wright notes the increasing variety of alternative energy projects now afoot in the economic development arena.

“I would hope that if that is the final direction this site takes, that it would support not only energy projects out there now, but new technology that’s going to be in effect five to 10 years from now,” he says. “With the research capabilities that are in the area, along with existing facilities and the support of TVA, that is very viable.”

William “Buster” Smith, 72, agrees. He proudly counts himself among the nearly 1,400 TVA retirees in the area, having retired 14 years ago as manager of properties after 25 years of service. So he knows whereof he speaks when it comes to energy efficiency and clean energy.

“I think it’s necessary for the future, especially energy conservation,” he says in a cellphone interview during a drive home from Montgomery. As for the property itself, “There’s a lot of acreage there, and good sites for varied types of development, not just energy.”

Hey, Portland: Biking to Work is Nothing New

In the meantime, the assets in Muscle Shoals sell themselves, beginning with the underlying layout begun by Ford and Edison, with streets and sidewalks and lighting all planned for easy access from one place to another. In fact, the tradition of TVA bicycles lives on today, and the pedestrian-friendly plan envisioned decades ago can now be called New Urbanist. Environmentalists have called for the entire property to become a wildlife preserve. But even in the R&D park scenario, the Lord Aeck Sargent study recommends that 60 percent of the property remain green space.

Hobson says there is a 69-kilovolt substation feed from Wilson Dam, and a water treatment plant on the property that takes water from the Tennessee River, cleans it and feeds it to all buildings, in addition to a separate water feed from a local distributor. Communication cabling and an extensive road system are there, and rail enters the property on its western side. There’s only one thing missing: an Interstate highway. Hobson says there has been some internal discussion about making the site part of the highly successful TVA megasite program, but the lack of Interstate access may prevent the site from becoming part of the program.

The range of buildings is wide, with some dating to the 1910s or 1920s and most in the warehouse category. TVA is now identifying which ones need to be kept for historical reasons. Hobson says some of the historic buildings are in good enough shape to be potentially rehabbed and reused as part of the overall redevelopment. “The production area of the fertilizer lends itself to an industrial type development,” he says. “We’d like to see some of those historic buildings reused in support of that.”

Others, such as a chemical engineering building, were built in the 1970s and have some facilities ready for reuse in their current condition.

“There’s been some interest in the bulk storage building for various uses,” says Hobson, “even movie and music production facilities.”

Such a use would blend in with Muscle Shoals’ other main claim to fame: the Muscle Shoals southern rhythm and blues sound that brought in so many recording artists in the 1960s and ’70s to what at one time was a whole family of high-quality recording studios, where a talented cadre of studio musicians, including the nicknamed “Swampers” cited in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama,” gave backbone and soul to many a track.

Capital of Training?

If some local and state leaders have their way, part of the Muscle Shoals redevelopment could amplify the state’s already sterling reputation for vocational training, education and talent development.

Gary Dan Williams, director of the Muscle Shoals Center for Technology, is spearheading a proposal to create the Tennessee Valley Career Technology Center on the site, a career and technical magnet school to serve high school students from around the state and perhaps across the Southeast.

“We have a proposal together that we’re hopefully going to submit to TVA this week,” says Williams. “In no way are we being so presumptuous as to think we have a birthright for anything. But we think we have a very good plan to do something very special not only in the local area, but perhaps a national school for highly skilled technicians” that could link with community college programs, apprenticeship training and four-year schools. He envisions a blend of academic, vocational and on-the-job learning that would unite the needs of industry and the work force, and stretch across a broad range of disciplines.

After all, some buildings in the area are still plenty active. TVA’s Environmental Research Center provides the entire agency with a wide variety of science, technology and support services to improve power-system performance and reduce the impact of TVA’s operations on the environment. The area is also home to the TVA Power Services Shops, which provide maintenance facilities and a work force of nearly 500 to service the fleet of power generation plants operated across the agency’s nine-state territory.

Williams, a native of the area, says his group’s proposal already has 40 letters of support from such people as Alabama Gov. Bob Riley, union leaders, company executives and educational institution leaders. He says the project builds on what’s already there, and on what’s unfolded there over the decades.

“I appreciate what TVA has brought to this valley,” he says. “TVA brought a good way for making a life for yourself around here. My granddaddy was a union carpenter. I go to the TVA site, and see the murals inside that rotunda, see them putting in a large generator, or see the farmer working with a government agent on how to terrace his fields. You see progress.”

Williams says the career center would be one catalyst of innovation on the redeveloped campus, “the next chapter” in progress for an area that “sure could use something.”

It’s not as if the area doesn’t have something going already.

The Conway Data New Plant Database has tracked projects in the area over the past couple of years from SCA Tissue, flooring maker Flexco Corp., Southwire and Total Support Tooling, among others. The area was picked a couple years ago for a major railcar manufacturing plant. But the jobs created there so far have come to just 150 as the economy tries to chug out of the great recession.

Original Mission

According to one person familiar with the redevelopment discussion, a lot of folks originally just wanted to tear everything down and sell off the land. But even in this early stage, most now understand the reason for an historic district to be established to protect certain properties. President Obama in March 2009 signed The Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, creating The Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area.

Thus do some dreams get memorialized. Ninety years ago, as brilliantly documented in the 2009 book “Fordlandia” by Greg Grandin, Henry Ford saw his vision of farms and factories living side by side go up in smoke, prior to repeating the error in the jungles of Brazil. Nevertheless, the parties now convening in Muscle Shoals might do well to pay heed to Ford’s words, however grandiose they may sound today:

“If Muscle Shoals is developed along unselfish lines, it will work so splendidly and so simply that in no time hundreds of other waterpower developments will spring up all over the country and the days of American industry paying tribute for power would be gone forever,” Ford told the Atlanta Constitution in 1922, a passage cited in Grandin’s gripping account. “Every human being in the country would reap the benefit. I am consecrated to the principle of freeing American industry. We could make a new Eden of our Mississippi Valley, turning it into the great garden and powerhouse of the country.”

New dreams are always being born. And still others survive in different form, like TVA itself. The patriarchal heritage of TVA also is something to be reckoned, as its roots — going back to the bulldog mentality of Senator George Norris — place the social, human aspects of economic development front and center.

That kind of progressive thinking can sometimes become bogged down in county and city politics (especially where so many jurisdictions are involved) or in over-thought strategic planning. It might be an upstream struggle to rival what gave the place its name: the series of shoals in the Tennessee River took a lot of muscle to overcome with oars and paddles.

But even with TVA’s dwindling activities and pared-down operational focus, there’s power, and then there’s power — of the sort that can’t be bought even by tycoons, but generated solely by years of built-up loyalty:

“If TVA will lead this through a public participation process,” says one observer, “the politicians will have no choice but to buy in.”